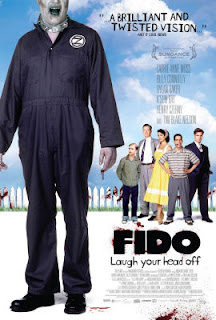

This weekend I had an opportunity to rent a few movies, and as I perused the shelves of my local video store I noticed a small number of DVD boxes that immediately caught my eye as the film Fido (Lionsgate, 2007) jumped out at me. I first heard about this interesting zombie comedy through the pages of Rue Morgue magazine several months ago, and shortly thereafter the television commercials for the film piqued my curiosity even more. Not many readers may have heard of this film due to its unique subject matter, and its likely limited theater circulation, but this is a film that is worth seeing, not only for those who enjoy zombie films and like to see a great combination of comedy and horror, but also for those who would like to think more deeply about some of the symbolism the film provides that touches on serious issues of society, culture, and yes, even theology.

This weekend I had an opportunity to rent a few movies, and as I perused the shelves of my local video store I noticed a small number of DVD boxes that immediately caught my eye as the film Fido (Lionsgate, 2007) jumped out at me. I first heard about this interesting zombie comedy through the pages of Rue Morgue magazine several months ago, and shortly thereafter the television commercials for the film piqued my curiosity even more. Not many readers may have heard of this film due to its unique subject matter, and its likely limited theater circulation, but this is a film that is worth seeing, not only for those who enjoy zombie films and like to see a great combination of comedy and horror, but also for those who would like to think more deeply about some of the symbolism the film provides that touches on serious issues of society, culture, and yes, even theology.

Fido takes place in a fictional and stereotypical suburban town in 1950s America. In many ways it might be seen as beginning where Sean of the Dead, another great zombie comedy, ended: a world characterized by a post-zombie apocalypse. As the story opens, the film draws upon the Romero zombie mythology where radiation has blanketed the earth resulting in the reanimation of corpses who now seek to consume the flesh of the living. This leads to worldwide zombie wars until a scientist creates an electronic collar that can be used to control zombies by removing their urge to eat human beings as long as the collar is working properly. This interesting use of technology by the corporation Zomcon (with the slogan “Better Life Through Containment”) leads to the domestication of zombies who become the servants for the living and who are then harnessed to engage in the necessary but menial tasks that make everyday life possible, whether the delivery of newspapers, gardening, or factory work.

The story then focuses on an American family desperately trying to keep up with the “Jones’s” who have (sometimes several) domesticated zombies, and not wanting to give inappropriate appearances, the housewife and mother (played by the Matrix trilogy’s Carrie-Ann Moss) brings a zombie into their home (who is later affectionately named Fido), much to the consternation of her husband and son, thus setting the stage for the dynamics that unfold for the rest of the film.

This film provides lots of humor, as well as lots of social critique. One of the interesting facets of the film brings critique to typical or stereotypical American families of the 1950s, and perhaps even beyond it. The family that provides the main focus for the film is comprised of an emotionally distant father, a wife who desperately craves his affection but is more concerned by what the neighbors think of their external image, and a son who desperately craves the attention and involvement of his father. These family dynamics are then explored through the introduction of the family’s “pet” zombie, who many times exhibits more emotion, and provides for a source of emotional connectivity, far more so than the “normal” living family members.

Beyond the critique of family relationships, the zombies in the film symbolize “the others” of society that take care of so many necessary areas of human life, but who many times are not valued or appreciated by more “mainstream” parts of our culture. One of the frightening aspects of this film is how quickly the zombies are dehumanized, even when they were quite recently valued by the living. This is humorously and tragically illustrated in the phrase “don’t trust the elderly” that arises in the film as a parody is offered from the old home medical alert badges for the elderly promoted through television commercials with an elderly woman who has fallen, and pressing her alert badge utters, “Help! I’ve fallen and I can’t get up!” A Zomcon commercial in the film parodies this classic commercial with the altered line of a family member shouting, “Help! Grandmas fallen and she’s getting up!,” meaning, she’s experienced a fatal incident and now she’s coming back as a zombie. Not to worry. Zomcon offers an elderly monitoring system designed to notify the corporation the instant that grandma or grandpa suffers a stroke, heart attack or other fatal ailment or accident. It responds quickly to take the former loved one away to the factory to be domesticated as yet another zombie product. Remember, don’t trust the elderly.

Fido also provides material for other areas of social and theological reflection as it looks at death and the funeral industry. In Fido‘s fictional world, the ever-present reality and threat of zombies has made specialized funerals necessary, those that provide for the detachment of the head and separate coffins and burial of the head and body that ensure zombie reanimation will not take place. This is yet another service provided by Zomcon, and it is a far more expensive process that only a few wealthy people can afford or desire. Most opt for becoming zombies after death. The film’s discourse on death and the funeral industry brings a harsh critique of the control and manipulation of the final disposition of our loved ones by an industry during a time of personal grief. In addition, aspects of the Zomcon funeral service in the context of a zombie apocalypze seem to raise questions about the Christian view of resurrection. Two funerals are depicted in the film, and in the first instance, as the minister holds the “head coffin,” he utters the words “From dust have you come, to dust shall you return, from dust shall you not be resurrected.” While the primary reference of this aspect of the service is no doubt to the process of reanimation in becoming a zombie, I found it interesting that the minister referred to a negation of “resurrection” rather than some other terminology or rising and “zombification,” seeming to leave open an interpretation with a theological application to the critique of the Christian tradition which still had strong social capital in 1950s America.

The successful mix of comedy and horror does not come along often. In my collection I have few DVDs in this category, and these include Young Frankenstein, and Sean of the Dead. I am preparing to add Fido to this collection, not only because of its wonderful mix of genres, but also because of its ability to provide food for thought and reflection on some of the pressing issues of our day.

2 Responses to “Fido: Rewarding Zombie Comedy Provides for Social and Theological Reflection”