This post brings together a number of areas of interest for me, including the increasing interest in fantasy with the counterculture of the 1960s, the connection between fantasy and Neo-Paganism, and the expression of elements related to Paganism and esotericism in film. We will explore issues related to these facets courtesy of an interview with Peg Aloi. Peg is a Pagan and a scholar who works in both the academic and popular arenas. She is a writer on Paganism and the media for Witchvox, is the co-editor with Hanna E. Johnston of the new volume The New Generation Witches: Teenage Witchcraft in Contemporary Culture (Ashgate, 2007), and is currently co-authoring a book with Hannah titled The Celluloid Bough: Cinema in the Wake of the Occult Revival.

This post brings together a number of areas of interest for me, including the increasing interest in fantasy with the counterculture of the 1960s, the connection between fantasy and Neo-Paganism, and the expression of elements related to Paganism and esotericism in film. We will explore issues related to these facets courtesy of an interview with Peg Aloi. Peg is a Pagan and a scholar who works in both the academic and popular arenas. She is a writer on Paganism and the media for Witchvox, is the co-editor with Hanna E. Johnston of the new volume The New Generation Witches: Teenage Witchcraft in Contemporary Culture (Ashgate, 2007), and is currently co-authoring a book with Hannah titled The Celluloid Bough: Cinema in the Wake of the Occult Revival.

TheoFantastique: Peg, it’s a pleasure to talk with you. Thanks for making the time, and for your recent help with my research project into cinematic treatments of the Witch. Let’s begin with a little of your background. How did you come to embrace the Pagan pathway, and why did this also become an area of academic specialty?

Peg Aloi: It’s a pleasure to do this interview, and it’s gratifying to see so much interest in Paganism and academia on the web these days. I also have to thank you for finally nudging me to finish Chris Partridge’s book [on the re-enchantment of the West] which is wonderful.

It is always interesting to me to hear how people first “found” Paganism or Witchcraft or Wicca, because even as there are any similarities that modern Pagans have in common when it comes to the roots of their backgrounds, there are just as many unique differences. For me, I was raised in what I’d call a somewhat lapsed Catholic household. My father wanted us to be good church-going Catholics but my Mom rejected the church based on, well, let’s say the local parish priest did not approve of decisions she made based on her doctor’s advice, and that was that. I did not know the reasons at the time, but I did know my mom did not have much use for the church. I just always found the experience of church to be both wildly exciting (the robes and songs and beautiful stained glass and shiny things) and incredibly boring (the liturgy and rote recitations) at the same time. Shortly after being confirmed I decided it was not for me at all, but I still had to go to church occasionally.

I was also required to attend religious instruction classes once a week; we called it “relidge.” It got interesting briefly when I had this teacher who told us juicy stories about teenage girls using Ouija Boards and doing séances at slumber parties who got into all sorts of trouble. It was real satanic panic kind of stuff, which was pretty ubiquitous in the 1970s when I stop to think back on it. The people who ran the classes, who were basically all volunteers from the parish, decided the students should all bring their Ouija Boards one night and we’d burn them in a big bonfire. I really wanted to go and see this spectacle, but I definitely did not want to burn my Ouija Board, so I faked illness that day. I guess I have a kind of perverse relationship to my Catholic upbringing!

More significantly, I was raised in a family that really valued the beauty and utility of the natural world. My dad was a hunter, fisherman and avid gardener, and my mom’s ancestors all had farms, so as far back as I can remember we were either growing or catching our own food, or going into the country to pick fruit or gather nuts. We’d spend summer days fishing or wandering around in the woods at my uncle’s place in Pennsylvania, or picking blueberries in the woods in New York. In winter we’d chop firewood and cut down our own Christmas tree and smoke a goose my dad had killed for dinner. At the time, this sort of thing was not considered unusual but it’s really a dying way of life in this country now…I mean, many families do not even cook dinner or eat together. If I were a sociologist, I’d love to research the connection of these sorts of foodways that are going out of fashion and chart their decline against the proliferation of Paganism and other nature-based spiritualities. I am completely convinced that my affinity and appreciation for nature and love of the natural world are a direct result of my childhood experiences.

As a child, I was always interested in the occult and Witchcraft. I remember seeing the movie Crowhaven Farm on TV when I was little and somehow identifying with the idea of someone being reincarnated as one of the Salem witches. My aunt and uncle let me watch The Exorcist on HBO with them, but made me cover my eyes during certain parts. I think I never actually saw the film in its entirety until the director’s cut came out a few years ago. I loved the images of Witches or other magical beings I saw on TV, I Dream of Jeannie was a favorite show of mine, and I loved The Twilight Zone. I vaguely assumed there must be modern witches somewhere in the world because the occult revival and the hippie movement were happening but had no idea there was any sort of living tradition in the United States, so I just devoured books on the history of the occult and folklore and the Salem witch trials and vampires and whatever.

I first found my way into the actual Pagan community when I was working one summer for Greenpeace in Amherst, Massachusetts. One night we were sitting around a fire after a day of canvassing, drinking beer and whatnot, and someone started doing some Pagan chants, you know, what we now call “Pagan Top 40” stuff like “The Earth is our mother” and that kind of thing. I was fascinated, here were these environmental hippie types, singing this Native-American-infused melody, it was the 1980s and the New Age was everywhere and I had only started to become aware that there was a Pagan community out there. Someone looked at me and said “Come on, Peg, you know the words!” I didn’t. But they were easy enough to pick up. We had some great times that summer, usually looking for secluded wooded areas to hang out in after work at night, sometimes swimming in forbidden places or sneaking onto private beaches on the Cape to sleep near the ocean.

Not long after this, I started to discover a Pagan community that was less connected to environmental or neo-hippie groups and more about Witchcraft and magic. I was attending the University of Massachusetts for graduate school, and one day I saw a flyer advertising the UMASS Pagan Student Organization. I think it was the first campus Pagan group in the US. I went to a meeting and, again, had this odd experience, just as with the Greenpeace group, of people expecting I knew more than I actually did. I had never attended a Pagan ritual before but at that first meeting when they were planning a Beltane ritual they asked me to be the high priestess. Who knows why? But I thought it was interesting that these strangers were assuming I was experienced in something I knew very little about, and I had not said or done anything to mislead them on this. Anyway, I hung out with these folks a while and they were not quite the kind of group I was looking for (they were a bit socially-awkward and not terribly interested in nature), but eventually I met some other people and attended all kinds of public and private events and I was off and running! I later moved to Boston which is a real vortext of Pagan community, so there was a lot going on, and eventually met people from the coven I later joined and still belong to. But now that I live in Albany, I do not attend rites as often and have become more of a solitary practitioner, which is what many people who belong to groups for a long time eventually become.

As for Paganism being an academic specialty of mine, well…I have an MFA in English. This is a terminal degree with a focus on creative writing. That and a couple bucks might get you a latte at Starbucks. I mean, it used to be a good degree but there are no jobs now, even PhDs are finding it hard. Fortunately, I did a minor in film when I was at UMASS. I also did an independent study course on Witchcraft in contemporary fiction, with a professor who specialized in myth and fantasy literature. After moving to Boston I was writing for an erotica magazine and a local arts weekly wanted to interview the women behind the magazine. This writer happened to be a film columnist and when he learned of my interest in film and my background he said he’d like to hire me to do short reviews for the paper. I had also taught a couple sections of Film and Literature in grad school. I did little bit of adjunct teaching here and there, including a course on Witchcraft in Film and Fiction. And eventually a friend I’d met through a film festival he was organizing hired me to teach at Emerson, where I have had freedom to develop a lot of unique courses. But I am still not really a bona fide film scholar or even a traditional scholar of any one subject. I have presented papers and published scholarly articles on everything from Celtic studies to travel writing to poetry, and of course film and media. The first time I presented a paper at a conference, the topic had a Pagan focus (it was on the unintentional destruction of sacred sites by Pagan tourists in the UK). Then the second paper I gave, I think it was on Buffy the Vampire Slayer, also had a Pagan focus. So I decided that every time I did any sort of academic presentation or research or published writing, it would have a pagan theme or focus. And that has held true for the last few years. It’s not like some sort of spiritual pact with the gods of livelihood, (here’s where I’d be laughing if we were doing this interview “live”), it’s just a quirky personal challenge that happens to fit well with my eclectic academic path. My spiritual path and my academic one have been similar in that they’ve both been rather untraditional, I guess.

TheoFantastique: How did you come to study film and its expression of the esoteric?

Peg Aloi: Like I said, I more or less fell into it. When I finally got a chance to teach something besides composition as a graduate teaching assistant, I had the choice of teaching Creative Writing or Film and Literature. Tough choice but I am glad I picked the film track as it has led to more teaching opportunities, and getting the job as a freelance film critic as helped, too. Anyway, one of the film classes I taught at UMASS was “Terror vs. Horror: The Psychological and Visceral Sources of Fear.” So of course I was exploring the difference between two models of horror cinema, the one a gory, shocking approach (such as one sees in slasher films, etc.) and the other a more subtle (but perhaps ultimately more unnerving) approach, the less-is-more approach. I wanted to try and expose students to things they might not normally think of as horror, like the Australian film Picnic at Hanging Rock, one of my favorites. At first glance, it looks like a costume drama but it has the qualities of mystery, horror and the paranormal as well. I am very intrigued by films that can’t be easily categorized, and television shows that meld different genres together, like Buffy or Twin Peaks.

My interest in the occult and in horror films has led me to design courses, on cinema and the occult, supernatural television, and Witchcraft and Paganism in contemporary media, and that’s all been really interesting, and the classes have been popular with students. Also, this is a very fertile field in academia now, especially since there is now a whole new branch of study known as “popular culture” which can be approached from within a variety of contexts. I have noticed for some time now that what we are currently calling “Paganism Studies” is still not a separate discipline unto itself, but is comprised of scholars whose specialties are very diverse: history, sociology, film and media, cultural studies, folklore, gender studies, you name it. And even if some scholars who want to be specialists in Paganism might find this frustrating, I think it works very well, in that it shows how this spiritual movement and its attendant imagery and texts and social implications have really permeated the culture in a very comprehensive and diverse way.

TheoFantastique: In a previous blog post I commend on Robert Ellwood’s observations of the influence of the “occult revival” of the 1960s counterculture on various aspects of popular culture such as television programming. You will touch on this in your forthcoming book. Can you summarize some of this revival for us, why it might have come about, and give us some examples of how it surfaced and continues to be worked out in television and film?

Peg Aloi: I think when one talks of an “occult revival” it is important to distinguish among the different occult revivals. There was an occult revival in England at the turn of the 20th century, one in the United States shortly thereafter, and one in the U.K. in the 1960s, concomitant with a revival in the U.S. The one we are most concerned with for our book is the most recent one, and in particular we wish to chronicle the ways in which film influenced it, and was influenced by it, both in the U.K. and the U.S. There are many factors which led to this revival, and interestingly these factors were quite different in these respective countries. For example, the rise of the American counterculture in the 1960s was a conflation of many societal tensions, including women’s liberation and the sexual revolution, civil rights, the Vietnam war protest movement, the environmental and back-to-the-earth movements, and of course drug use and, overlaying it all, the increasing social influence of popular music. As well, various works of literature were influential, both older classics and newer works. All of this had an impact upon increasing interest in the occult and the spread of Neo-Paganism. (Of course, the occult and Paganism are not the same thing, but there was and is enough overlap of these communities that they are generally seen as being interchangeable, at least to the mainstream observer). The U.K. did not have the same stake in the Vietnam situation, but the runaway popularity of the Beatles and their ability to directly influence the youth culture through their own spiritual exploration (after 1966 the Beatles were pretty much done with pop love songs) generated a similar sense of unrest among working class youth, and just as the British Wave of music had dramatic impact on the U.S., the energy of the American counterculture infused this unrest in the U.K.

As everyone knows, the behavior of many young people during this period of social unrest was seen as a very negative and corrupt trend in the culture, not to mention the widespread political shift. Once people started to really understand the atrocities and the rather hopeless situation in Vietnam, the general population followed the lead of the young in denouncing the American government’s actions; but at the same time, there were so many other aspects of youth culture that were widely disapproved of, and the occult was part of that. Sex, drugs, rock and roll: this phrase had both very negative or very positive connotations depending which side of the fence you were on. I think this was a source of great ideological conflict for many people and I picked up on it as a kid (I was born in 1963). I mean, on the one hand, everyone thought that the wholesale slaughter of young men was a problem; but some people were still caught up in the 1950s and early 1960s- era fear of Communism and the Cold War and were very protective of their burgeoning American dreams. Obviously, change was in the air, and the religious underpinnings of American culture were becoming unmoored by the large questions of morality that were blazing on American TV screens and newspapers. The coverage of the war was something no one could argue with: in those days, journalism was still a very straightforward and objective discipline. The images of Vietnam spoke for themselves. This really primed the canvas for the media to have a huge influence on the culture.

Those areas of social tension I mentioned earlier were and in many ways still are seen as “liberal” causes and interests. Which made the adoption of Pagan mindsets, such as earth-based spirituality and nature worship which are part of modern Wicca and other paths, seem like a natural outgrowth of the social zeitgeist. But interestingly, in the U.K., the factors which led to a Pagan revival were seen as “conservative” or right-wing sorts of issues. Ronald Hutton discusses this far more eloquently than I am doing in Triumph of the Moon. So not only were the roots of the revivals different, the types of people interested in them may well be very different. On a personal note, I have noted an interesting difference between American and British Pagans during my travels in the 1990s, that, in general, manifested in a much more male-dominated and dogmatic way of doing things than once sees in the more goddess-centered, eclectic paths in the U.S. The reason I mention all this is that I think we will find in our research that the popularity of certain occult film texts in both these nations will be to some extent a reflection of the occult communities.

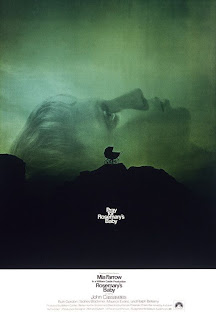

But to offer a summary of the occult revival in film, for the purposes of our book we will probably try to determine a singular moment when it all began. Since we are mainly interested in popular culture, we will consider the influence of the works of experimental filmmaker Kenneth Anger in the 1950s. But the first example of occult cinema that had widespread and culture-changing impact was Roman Polanski’s 1968 film Rosemary’s Baby. In addition to its being a very artful and entertaining film, based on an equally artful novel by Ira Levin, there were some real-life occurrences that added to its aura of evil, and fuelled a widespread spirit of protest against all things occult, even as the film ushered in a palpable fascination with the occult. Namely, the murder of Polanski’s pregnant wife, actress Sharon Tate, by the members of the Manson family. Not long after, Polanski was accused of raping a 13-year old girl, and has lived abroad ever since because if he ever enters the U.S. again he will be indicted on that crime. Because the news media today is so obsessed with crime and scandal, we might think such a story is all in a day’s news. But at the time, the Manson family’s killing spree was a horrific, almost surreal narrative that engendered fear of “murdering cults.” Their association with the lyrics of various Beatles songs (scrawled on walls at crime scenes) helped convince the public that their aberrant behavior was somehow the result of the cultural climate.

I think also this is where the word “occult” became imbued with such negativity, because of course Manson’s clan were referred to as a “cult” under the influence of this crazy, charismatic guy. I hate to suggest the American public is incapable of making the distinction between these two very different words, but I recall the word “cult” became a buzzword associated with anything “occult.” What we now call “satanic panic” has its roots in the fear of the public that any sort of interest in the occult (evidenced by the Beatles lyrics that reflected their interest in Eastern spirituality and social protest) could potentially lead to involvement with murdering cults. A ridiculous leap in logic, perhaps. Anton LaVey founded the Church of Satan in 1966, and his spurious claim that he portrayed the demon who impregnated Rosemary in Polanski’s film further reinforced the idea that fiction and real life were frighteningly linked. And the portrayal of the “old folks next door” as a coven of murdering witches was somehow both campy and horrifying. Suddenly your neighbors were capable of anything. By the time The Exorcist came out in 1973, portraying incidents of Black Mass desecrations and the demonic possession of a pre-pubescent girl, the American public was completely convinced that Satanism, Witchcraft and the occult were a dangerous trend stealing away the souls of our young people. I mean, little Regan had a Ouija Board! I am sure that was the reason for why I was encouraged to burn mine. Then Linda Blair went on to star in all these rather shocking made-for-TV films, which were great, but underscored again that this actress played nothing but troubled or evil characters.

It’s also true that we saw a real dearth of occult film and TV in the 1980s, and I think that is directly due to the rise of the Moral Majority under Reagan. It was not until the early 1990s, when we saw the rise of the New Age and Neo-Paganism and Wicca, that we see a return to television of occult, Pagan and paranormal shows, like The X-Files or Xena, Warrior Princess. Let’s face it, Buffy could not have existed without Xena.

TheoFantastique: Scholars like Christopher Partridge in the U.K. have commented on this and referred to it as a process of re-enchantment in the Western world. He says this has given rise to a “popular occulture” that surfaces not only in film and television, but also video games and music. Would you agree with this sentiment? And if so, how would we differentiate between esoterically-influenced forms of pop culture and a simple increased interest in general fantasy, myth, and fairytales?

Peg Aloi: I think Partridge was right to try and explore the shift in those terms. I also appreciate his use of the term “neo-Romanticism” over other descriptive terms because if you really look at it, the Romantics were so very instrumental in both periods of occult revival. Without the poetry and perhaps more importantly, the ideology of the Romantics, which of course was rooted in a desire to revive the imagery of classical mythology and the dream of the pastoral life, Neo-Paganism would never have happened. Some theorists also credit the Romantics with influencing not only the occult revival but the entire 1960s cultural shift. Camille Paglia wrote an essay exploring various aspects of this, including the idea of rock music and the live concert experience as an expression of Dionysian impulses. We had a movement in the 1980s called “New Romanticism” which was mainly about music and fashion…and to some extent a renewal of interest in Romantic poetry and the paintings of the Pre-Raphaelites, for example. Partridge acknowledges the influence of various works of fiction on renewed interest in fantasy and fairy takes but also in Pagan worldviews and alternatives to mainstream spirituality, in particular Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy and, more recently, Terry Pratchettt’s Discworld series. Then there was the very popular artwork throughout the late ’70s and ’80s of Brian Froud, Boris Vallejo, Sulamith Wulfing, Susan Seddon-Boulet and others. That kind of art is still very popular with lots of new artists joining the ranks, although it seems to me it is getting more and more twee, maybe because it’s all aimed at little girls now. I don’t think there necessarily was or is a general increased interest in fairy tales that has fed the trend in literature and art; I think a few writers and artists whose personal visions have led them to produce work concerned with these worlds is what has fuelled that revival of interest. And I think perhaps their interests are more likely to have originated in esoteric interests, at least Pratchett’s. But there have been non-fiction works that no doubt influenced this as well, such as the work of Joseph Campbell, which started to be popularized in the 1980s thanks to Bill Moyer’s televised interviews. Or the documentary film version of The Ascent of Man.

I think it’s very complex and difficult to trace what influenced what, because clearly there is a lot of overlap. I mean, I personally think video games that are very fantasy-oriented these days have their basis in role-playing games which started in the late 1970s with Dungeons and Dragons, which of course was directly influenced by Tolkien’s worlds and lexicon. To be honest, I think that the reach of popular culture has become so pervasive and in a way insidious, in that many of us may have no idea where an idea or image or cultural trend of phrase first emerged. This makes it hard on artists because often their ideas or work is imitated and then it is the imitation that gets noticed more widely than the original. This has certainly been true in terms of Pagan literature and art. For years now I have abhorred the trend in the Pagan community to value mediocrity, to choose the cheap imitation over the original. Maybe we have the mainstreaming of Paganism to thank for this. And people also choose the simple over the complex, the quick fix over the thoughtful solution. Someone can become a Witch overnight, no need to engage in training or study, We certainly have Llewellyn Publishing to thank, or blame, for this. That’s not to say all their books are bad, or their practices are questionable, they simply gave the public what it wanted.

Something else that intrigues me about the idea of “occulture” is the way in which some entities have co-opted the imagery or message of the occult or Paganism in order to subvert its actual ideology. I have noticed a really disturbing trend in late night television commercials for the army, though: they have these really well-produced, special-effects laden ads that make military maneuvers look exactly like role-playing games, and seem to be suggesting that, if you are good at video games, you’d be good at using this equipment. But it seems really odd to me to suggest that the sort of teenager who would be interested in fantasy video games (and who this sort of ad is clearly aimed at) would be someone inclined to join the army. Now with all the young men and women at risk in the Iraq war, I wonder if this sort of advertising campaign has been successful in reaching disaffected young people. The majority of soldiers killed have been very young and from very small towns. Okay, I am starting to think I don’t want to take this too much further but readers can draw their own conclusions.

TheoFantastique: There has been a close connection between speculative fiction and Paganism for some time, from interest in the writings of H. P. Lovecraft to Robert Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange World informing the mythos of the Church of All Worlds. Why do you think there is such a strong connection between Paganism and speculative fiction in its various forms?

Peg Aloi: As I understand it, speculative fiction, is different from science fiction in that it posits a possible and plausible future based on the way things are now and the way things seem to be going. So in science fiction, it’s all about space travel or technology, but in speculative fiction you see a lot of interesting ideas having to do with things like ecology, biology, evolution, politics, gender and sexuality, societal structure, drugs, etc. Sometimes this kind of fiction posits a very positive vision, as with the Heinlein book, and sometimes a negative one (like Ursula LeGuin’s The Word for World is Forest). Speculative fiction often functions as a cautionary tale, and usually offers a hopeful vision, because it can point out the mistakes made along the way and perhaps inspire ways to avoid an undesirable future. At its heart, the Pagan revival is a form of speculative fiction. Modern Pagans look at the world as it is and want to change it. They (we) see a lack of connection to nature, resulting in a range of problems from pollution to obesity. We see a dearth of compassion, leading to a loss of civility and cultural awareness. We see the absence of the childlike sense of wonder all humans need to access from time to time, which is making us all cynical and depressed. We see a failure to challenge and engage our children in traditional ways, which is making our children into spoiled, underachieving, entitled little zombies. We see an obsession with technology that is making us lose touch with what it means to be human.

Paganism means rejecting the world as it is, and sometimes you find Pagans who try their best to live in a sort of fantasy world. They might spend too much time involved with sub-cultural communities or role-playing games or escape into literature or the Internet. To some extent this kind of activity can help perpetuate the popular stereotype that Pagans are anti-social or geeky or whatever. But most Pagans want to effect change in ways that will effectively allow them to exist in the world as it is, but to improve the quality of life and in some cases, effect change in the culture. To do this they look to “the old ways” and to ideas, images, stories and myths of the past, and integrate this into contemporary living, using whatever technology and products are available. And now you see a real integration of different kinds of subcultures that are engaging with Paganism. It is impossible to gauge the importance or the Internet in spreading awareness and information, but of course it also levels the playing field and perhaps makes Paganism less unique or special. And of course some “old school” Pagans would rather have the community remain insular and underground, but there is no turning back now. I do think modern Pagans should give some thought to how such changes are affecting our spirituality and social interaction. The only way to get any perspective on this kind of thing is to remove yourself from it for a while. Which is why I like to attend Pagan gatherings outdoors where you can remove yourself from the online milieu and see how this movement really is a living one.

TheoFantastique: What do you think the future of our media culture holds for the continued expression of esotericism in cinema?

Peg Aloi: It’s been interesting to see the response to esoteric texts aimed at children. The Harry Potter franchise has been hugely popular and also has generated a lot of rage. People ban the books and burn them and actually think that the whole Hogwarts model is endangering our children by introducing them to Witchcraft. Some protest literature even tries (ineffectually, in my opinion) to compare the Hogwarts style of magic to Wicca, which it has nothing to do with, of course, but the kind of people who want to ban a series of books that actually get kids reading again are the kind of people who want as accessible a target as possible, and Wiccans are the new Satanists, really, aren’t they? There is a growing atmosphere of protest aimed at the new film The Golden Compass (based on the first book in Philip Pullman’s trilogy His Dark Materials) have garnered accusations of promoting atheism and being anti-Catholic. I did not read the books but having seen the movie I can’t understand where these accusations come from at all!

I have also heard that the studio funding for the sequel to The Wicker Man being filmed by Robin Hardy, Cowboys for Christ, is being held up because some of the financial backers are fundamentalist Christians offended by the title. It seems unlikely there will a change anytime soon in this kind of public scrutiny. I won’t get into the whole political situation we’re in now and how there is really a problem with people recognizing the appropriate separation of church and state. But clearly the climate of indignation and panic-mongering about the future of our children goes hand-in-hand with the very pervasive effort to turn this into a Christian, right-wing nation. It’s really feeling like the 1980s all over again, where the public outcry against the occult really did lead to an avoidance of occult topics in popular media. The only difference between how things are now and the more visible kinds of protest one saw during the era of satanic panic in the 1980s, is that the protest is now taking place among well-organized groups on the Internet, which is of course where many people believe all the most significant cultural discourse is taking place (she said/typed, in the interview which will appear on a popular esoteric blog).

TheoFantastique: You’ve already alluded to this, but does Paganism and esotericism in pop culture represent a continuing area of promising possibilities for researchers from a variety of disciplines?

Peg Aloi: Oh, absolutely. We’ve been seeing a surge in this for some time now. Perhaps the one place this really caught fire was within Buffy studies. The first international Buffy conference in England represented an astonishing array of disciplines. That was where I met Hannah. There were talks on Buffy that explored this TV show from very diverse contexts, including history, media, literature, psychology, ethnomusicology, queer studies, anthropology, etc. It was amazing. I think that has really helped set the tone for academic conferences that deal with Pagan-oriented topics as well, and in fact a lot of the same scholars who are into Buffy are also involved in Paganism studies. Hannah and I have co-organized two conferences with the Department of Folklore and Mythology at Harvard, the first one on Witchcraft and Paganism in Contemporary Media, and the second on Paganism, Folklore and Popular Culture. These were both very successful and dynamic, and the most exciting part was the wide variety of disciplines represented, even for the media conference.

One thing that has changed a lot since the 1980s is that now it is permissible to approach topics in Paganism and the occult as someone who is both a scholar and a practitioner. It used to be sort of controversial to be “out” as a Pagan if you were studying Paganism; partly because being an ethnographer usually connotes the image of an outsider. When Tanya Luhrman’s book came out (Persuasions of the Witch’s Craft) people were conflicted; it was a great book, very sensitive and thorough and insightful, but she posed an interested seeker to gain access to rituals and private Pagan events. I think that made some Pagan scholars uncomfortable and in some cases stymied their efforts to do research within the Pagan community. I also think that academics in the 1980s risked being seen as “weirdos” or being targeted with discrimination in the workplace if they came out as Pagan, but there is so much more awareness now of what contemporary Paganism is, it is less of a problem. This new trend of research being conducted by believers and practitioners is definitely an exciting trend, but a problematic one, too. Just as you find non-academic Pagans who are very dogmatic or inflexible in their beliefs, some academics are the same way, and in some cases may unwittingly or even intentionally imbue their work with aspects of their own beliefs or traditions. It is obviously crucial to remain as objective as one can if one is to maintain an academic perspective. This is the new challenge for Pagan and occult academics: objectivity fuelled by study of the many diverse traditions and expressions of esoteric beliefs and culture.

TheoFantastique: Peg, thanks again for sharing with us. I look forward to hearing more about your book as it nears completion. Please keep in touch so that we can promote the book when it becomes available.

Peg Aloi: It has been my pleasure! Thanks again for your interest and support.

2 Responses to “Peg Aloi: Cinema and the Occult Revival”