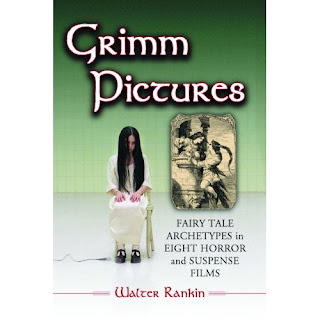

In my research for materials that address issues related to this blog’s focus I recently came across an intriguing book by Walter Rankin titled Grimm Pictures: Fairy Tale Archetypes in Eight Horror and Suspense Films (McFarland, 2007). As the title indicates Rankin makes a connection between archetypal images, themes, and symbols and contemporary horror and suspense films.

In my research for materials that address issues related to this blog’s focus I recently came across an intriguing book by Walter Rankin titled Grimm Pictures: Fairy Tale Archetypes in Eight Horror and Suspense Films (McFarland, 2007). As the title indicates Rankin makes a connection between archetypal images, themes, and symbols and contemporary horror and suspense films.

Dr. Rankin is Deputy Associate Dean and an affiliate associate professor of English and German at George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia. He made some time recently to talk about issues related to the thesis of his fascinating book.

TheoFantastique: Dr. Rankin, when I came across your intriguing book the title and thesis caught my eye. As the description in the masthead of this blog indicates, an exploration of archetypes in popular culture such as horror and suspense films is in keeping with the areas of interest for this forum. Before we discuss your book, can you tell me how you came to be involved with such interests? How does your work as a professor of English and German intersect with an exploration of archetype in horror?

Walter Rankin: The Grimm Fairy Tales have been a part of my life for as long as I can remember. My mother used to read the original tales to me as good-night stories, and she had no problems with the violence and horror in them. There’s a nice simplicity to most of the tales that everyone can relate to, especially children: Good people go through a tough trial against a worthy foe and emerge victorious. And despite their fantastic elements, the tales have real-life themes. For example, Hansel and Gretel are starving children in a poor home, while both Snow White and Cinderella have to face the loss of their beloved mothers and then deal with their scheming stepmothers. As a professor, I’ve found that works of horror and suspense – and certainly popular culture – do not always get the respect that they are due. The truth is, it’s hard to construct a good, scary story with compelling characters with whom your audience can identify. The Grimm Fairy Tales do this is a way that has allowed them to remain popular and to serve as archetypes for other works of horror and suspense.

TheoFantastique: I think most adults would not associate Grimm’s Fairy Tales and its archetypes with horror and suspense. How did you make this connection?

Walter Rankin: Whenever I teach the Grimm Fairy Tales, my students are always surprised at the level of horror and suspense maintained in the tales. The canonical tales (like Cinderella, Snow White, Rapunzel, Hansel and Gretel, Red Riding Hood, and Rumpelstilskin) have been sanitized and watered down quite a bit in modern retellings and children’s books. In Disney’s Cinderella, for example, we see the heroine communing with nature and singing to little birds. In the Grimm version, Cinderella still talks to birds, but this time she has them peck out the eyes of her stepsisters. Similarly, Rapunzel doesn’t just wake up to a handsome prince in the Grimm tale; rather, while she sleeps for a hundred years, we learn that many other princes have endured agonizing deaths in the thorny brier surrounding her castle. My favorite is dear Snow White who invites her stepmother to her wedding so that she can have red-hot iron boots strapped to her legs. The wicked queen is then forced to dance to death in them.

TheoFantastique: So in some senses then would you consider the various archetypes that surface in horror as functioning as a form of fairy tales for adults?

Walter Rankin: Absolutely – I think these archetypes become a part of our shared, subliminal consciousness that informs how we – as adults – then view horror and suspense films. The Grimm Fairy Tales include strong messages for adults as well as for children, and these translate easily to modern horror. A lot of the tales are about really bad parents, for example. In “Hansel and Gretel,” the father takes his children into the forest twice and leaves them for dead so that he and his wife will have enough food; in “Rapunzel,” the parents essentially sell their daughter to the neighboring sorceress in exchange for a good salad; in “Cinderella,” the stepmother has her own daughters cut off their toes and heels so that they can fit their bloody feet into the famed slipper. We can identify with these tales, because these parents really exist in our own world – babies get left in dumpsters, mothers drown their own children, and child abuse exists in all levels of society.

TheoFantastique: What types of archetypal images, themes and symbols have you identified from Grimm that you see surfacing in contemporary films?

Walter Rankin: Films like Halloween, Friday the 13th, and, more recently, Scream, all give us the archetypical Grimm version of Sleeping Beauty. The heroine feels safe and secure in her home environment only to discover that a male “suitor” is determined to get her. Like the suitors in the Grimm tale, they are relentless stalkers who will stop at nothing to get their prize. Films like Single White Female and The Talented Mr. Ripley hit upon the Snow White themes of same-sex jealousy and obsession, as the popular characters find themselves losing their lives to their rivals. The central theme in these works is that there really is only one fairest in the land. Perhaps the most enduring archetype is that of the disguised wolf. In the Grimms’ “Little Red Cap,” our heroine is tricked by a smooth-talking wolf who then impersonates her grandmother and eats her. The best example of the disguised wolf comes from The Silence of the Lambs (both the novel and, my primary focus, the Oscar-winning film starring Jodie Foster and Anthony Hopkins).

TheoFantastique: One of the films you look at is the 1968 film Rosemary’s Baby directed by Roman Polanski. Can you discuss the fairy tale aspects you see in this film and how this is portrayed for a contemporary audience?

Walter Rankin: I tie this film directly to “Rumpelstiltskin,” in which a young woman sells her first-born child to the strange little man so that he will spin straw into gold. By doing this, she gets to marry the king. Then the only way that she gets to keep her baby is by guessing his name (which she does by having servants spy on him). We know nothing about Rumpelstilskin really, other than he wants a living child. He’s considered devilish, but he is not specifically labeled a devil in the tale. In Rosemary’s Baby, we get another young woman (Mia Farrow) whose baby is sold by her husband to a group of devil-worshippers. As in the fairy tale, her husband benefits greatly by this bargain. Like the fairy tale queen, Rosemary can only figure out what has happened by deciphering a name (in this case, her neighbor, Roman Castevet). Both the film and the tale also have amazingly ambiguous endings that leave their audience guessing. Most fairy tales end happily ever after. In “Rumpelstilskin,” however, the queen has kept all of her dealings with the little man a secret from the king. If he ever asks her to spin gold again, her lies would be discovered, and she would be killed. As Rosemary’s Baby concludes, the initially horrified mother comes to accept her baby and love it. The camera pans out over the city as a lullaby plays, and we’re left wondering what will happen to her, the baby, and the world itself.

TheoFantastique: The cover of your book includes images from a fairy tale illustration and one of my favorite contemporary horror films The Ring. What connections do you make between these two?

Walter Rankin: This film hits a number of archetypes found in the story of “Rapunzel.” Let’s start with the main image in both – flowing tendrils of hair define Samara in the film and Rapunzel herself. Both characters are isolated from the outside world in remarkably similar settings. Rapunzel is hidden away in a tower with only a small opening at the top; likewise, Samara is kept hidden first in a barn attic with a tiny ladder leading up to a loft and then, most strikingly, in a well that has just the one entrance. Both of these tales focus on extreme isolation and lonliness as well as parental betrayal. In “Rapunzel,” the parents have sold their daughter to the neighboring sorceress, while Samara’s own (adopted) mother is the one who plunges her into the well.

TheoFantastique: You also discuss parallels between the fairy tale story of “Little Red Cap” and the 1991 film The Silence of the Lambs. Can you touch on some of this?

Walter Rankin: The Silence of the Lambs has so many incredible images and themes that tie it to “Little Red Cap,” in my opinion. Right from the beginning of the film, the audience sees a lone, red-haired woman (Clarice Starling) running down a forest path. Thus, we are plunged immediately into an archetypal fairy tale realm. Once here, we learn of two wolves: Hannibal Lecter and Buffalo Bill. Hannibal acts like the charming wolf on the path who sweet-talks the young girl so that he can get information. He also seems to feed off of Clarice, particularly her painful childhood memories. Buffalo Bill gives us an even more direct link, since he’s making a dress out of real women. In the famous tale, of course, the wolf eats the grandmother and puts on her clothes and nightcap. The Grimm tale has a hunter come along to cut Little Red and her grandmother out of the belly of the wolf; however, the little girl doesn’t just run home. She gathers stones and sews them back into the dozing wolf’s stomach. When he wakes up, he topples over and dies from the weight. She’s also learned a valuable lesson, and the next time she visits her grandmother she avoids another wolf and manages to bring about his downfall as well. The moral is clear: Dangerous wolves can be disguised anywhere and are ready to pounce, so be on your guard. Starling, too, must learn this lesson, which is beautfully realized at the end of the film. She encounters Buffalo Bill in his home alone, and he retreats to the basement. Here, he turns out the lights and puts on his own night-vision goggles. This is, metaphorically, the dark belly of the wolf. Despite his physical advantages, Starling is shown to be smart and thorough. When she almost instinctively turns and kills him, a bullet breaks through the darkened basement window and light streams in. Thus, she is like Little Red emerging from the fairy tale wolf’s stomach into the clear daylight. She graduates from the FBI academy and Dr. Lecter calls her, letting her know that even with one wolf gone, another one is always nearby.

TheoFantastique: In my view some of our most popular stories like Harry Potter also draw upon archetype and myth and function as fairy tales for young and old alike. Would you agree with this sentiment?

Walter Rankin: I definitely agree – what’s fun about Harry Potter and similar tales is how they take familiar archetypes and images (witches and wizards, wands and spells) and update them in unique ways while keeping the heart of a good story. Harry Potter is similar to any number of fairy tale heroes – his parents are dead, his caregivers, such as they are, are cruel – who have to go through great trials to become fully developed adults. While many readers were sorry to see Rowling bring the story to a close, I think she made the best artistic decision, giving the story the kind of closure found in most fairy tales.

TheoFantastique: Dr. Rankin, thanks again for these thoughts. I hope this interview helps generate interest in your book among its readers.

Wow! This is a great blog and the post on fairy tales is brilliant! I have my own blog that students in my college level writing courses use. It’s very basic, but I’d love to link to your blog on mine. And vice versa, if you are interested.

There’s really thoughtful, rich stuff on your blog!

I forgot!

My blog is diamondsandtoads.blogspot.com

Students really respond to it and I’d love to link to your so they can see it!

Thanks!

Katew

Kate, I’m glad you found this post helpful for you and your students. By all means, feel free to link to this blog from your own as a further point of interest and assistance to your educational program.

I never would have connected Rapunzel and The Ring that way, but it’s a really good point.

Another great thought-provoking entry. Thanks.

Excellent post brother.

I want you to know that I love your blog. It is awesome to say the least. I love the way you think and the way you get others to think as well. I want to let you know that I have added you to my favorites and will be checking in regularly. I pray that God will bless you this year. I hope that 2008 will be the best year in the LORD JESUS CHRIST!

In Him,

Kinney Mabry

AKA

Preacherman

P.S.

You are always welcome at my blog as well.

Fascinating. I’m ordering the book immediately. I’m also going to crack open my Grimm’s book and reacquaint myself with those wonderfully gruesome stories.