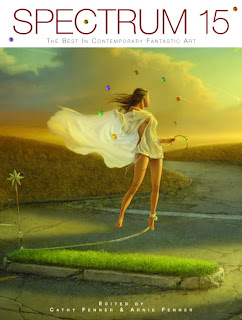

One of the ways in which I enjoy the fantastic in popular culture is through art. And there may be no greater collection of fantastic art than the annual volume of Spectrum: The Best in Contemporary Fantastic Art. I recently spoke with Arlo Burnett, the Administrator for Spectrum, who shared his thoughts on this inspiring publication.

TheoFantastique: Arlo, thanks for making some time to talk about Spectrum. I am a late comer to discovering this great collection of fantastic art with Spectrum 12 as my first introduction to the publication. Can you talk a little about how Spectrum came together as a publication some 15 years ago?

Arlo Burnett: Certainly! Spectrum grew from a desire of Arnie and Cathy Fenner’s to create an amount of respect and validity to the field of fantastic art. At the time, artwork in this field was dismissed out-of-hand and not taken seriously — even by those within the illustration community. Another desire of theirs was to generate a level of recognition for the artists as well. Artwork had a tendency in the past to become separated from the artists who created it, and having it all collected into a book focused on the art instead of what it was trying to sell (be it a book, album, or product advertisement) afforded the opportunity to attach names to the work. Proposals made by Arnie and Cathy to have someone produce a book collecting the best examples of contemporary fantastic art failed to garner anything beyond initial interest, and as a result they made the decision in 1994 to put the book together themselves.

TheoFantastique: For those who may not have seen the publication, can you describe the various categories of fantastic art and the media that the artists work in that are featured in Spectrum?

Arlo Burnett: Spectrum initially began with the Advertising, Book, Comics, Editorial, Institutional, and Unpublished categories. All six are pretty self-explanatory except for Institutional — we often get questions about that one. The Institutional category was set up as a catch-all for art projects such as artist self-promotion materials, album covers, calendars, etc. which may fall outside of the other clearly defined categories. It was with the third volume that the need for a Dimensional category was recognized, and so it was added as part of the submissions process for that book. Some years later, an increase in the submissions of concept designs which came as a result from the rise of video games and studio development of film franchises led us to re-examine the categories once again, and the Concept Art category was introduced in Spectrum 14 as a result. As for the media used by the artists, we receive submissions that run from oil on canvas to digital creations in Photoshop — and everything in-between. The only requirement is that the artwork falls into the realm of “fantastic art” — which, as long as it provides a unique take on the world around us, can be a pretty broad category.

TheoFantastique: What are the sources for the artwork in terms of publishing venues for the artists? Is there greater representation in books and comics, for example?

Arlo Burnett: It may come as something of a surprise, but the category which has the greatest number of submissions year after year is actually Unpublished. A reason for this is one that I gave as part of the desire for creating the book — artist recognition. Art directors and other industry professionals have an opportunity to see some of the artwork created outside of the established field, and those professionals now have an opportunity to put names and contact information to the art which could lead to work down the road for the artists. I have also found that entries in the Unpublished category often challenge the field of fantastic art either by turning established genres on their ear, or by bringing something entirely new to the table. It’s always quite exciting to see unpublished work as it comes in because today’s entries could become tomorrow’s trends.

TheoFantastique: Do you think there has been an increase in the interest in fantastic art, and if so, why do you think this is?

Arlo Burnett: Absolutely! I think a large part of the interest originated in the late’70s. George Lucas started the process rolling and passed it on to Ridley Scott who then handed it on to James Cameron. Three directors who couldn’t be more different from one another managed to each create something singular in the field. Lucas found acceptance with the general public through Star Wars, Scott fully realized an artistic vision of the future with Blade Runner, while Cameron pushed the envelope of visual effects with Terminator 2. While it could be argued that there are better examples than the ones I’ve given above, I truly think that we have begun (and will continue) to see the impact on an entire generation resulting from a series of films made over the course of 15 years by these directors. It’s hard to find television and movies today which reference pop culture that don’t manage to quote Star Wars to some degree. It’s also equally as hard not to go shopping or drive along an interstate without seeing an LCD billboard of varying scale serving up an advertisement. Even more difficult today is to see a movie which hasn’t been enhanced using computers in some fashion.

TheoFantastique: You recently completed work on Spectrum 15, which will be available from Underwood Books this fall. And I understand that you will be accepting entries for Spectrum 16 beginning in late October this year. What are some of the challenges faced in putting this book together?

Arlo Burnett: The first major hurdle in compiling the book is collecting all of the artwork which was accepted by the jury. Although we do request that artists submit reproductions of their work for the jury to view, it is better to have source images on hand when assembling the book for publication. Amassing all of the images and keeping track of what we receive is no small feat, but thanks to easily accessible high-speed Internet connections, more options are available to the artists to send their accepted images which negates the added cost and time of standard mail delivery. The second obstacle is the process of assembling the book layout. Certain pieces have a tendency to overwhelm others that may appear on the same spread, so finding the right balance of images is a delicate line to walk each year. Another important part of the layout is affording each piece some room to breathe. One way in which this is achieved is by increasing the number of pages in which the artwork appears. The page-counts in Spectrum have continued to increase throughout the years with Spectrum 15 weighing in at 264 pages –both out of necessity for space between the pieces appearing inside and due to the increasing quality in the submissions we receive every year. The final challenge is waiting for the finished product to return from the printers. Heavy storms, availability of paper, and dock strikes have all affected to some degree the arrival of the books on store shelves.

TheoFantastique: Care to pass along any tips to artists who’d like to see their work included in a future edition of Spectrum?

Arlo Burnett: The best tip I can pass along to interested artists would be to send in an entry. Sometimes the toughest challenge

for artists to face is the decision to enter their work in something on an international scale –understandably so. However, a piece can’t be selected for Spectrum if the jury hasn’t had an opportunity to see it, and every entry we receive goes before the jury for consideration. Sending in an entry may sound like a simple piece of advice, but it is a crucial first step for artists to get their work in the book.

TheoFantastique: Arlo, once again, thanks for taking time out of your schedule to discuss this great publication.

Arlo Burnett: It was my pleasure, and thank you for taking the time to do this interview for your readers!

One Response to “Spectrum Interview: The Best in Contemporary Fantastic Art”