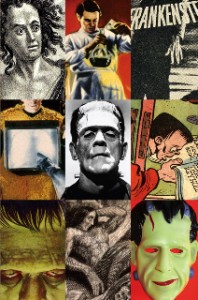

Not long ago I came across a book in the Cultural Studies section of Barnes & Noble that caught my eye. It was Susan Tyler Hitchcock’s Frankenstein: A Cultural History (W. W. Norton, 2007). Susan is a nonfiction writer and editor with a PhD in English. She has written a number of works, and after contacting her she graciously agreed to share her passion for Mary Shelley and Frankenstein.

Not long ago I came across a book in the Cultural Studies section of Barnes & Noble that caught my eye. It was Susan Tyler Hitchcock’s Frankenstein: A Cultural History (W. W. Norton, 2007). Susan is a nonfiction writer and editor with a PhD in English. She has written a number of works, and after contacting her she graciously agreed to share her passion for Mary Shelley and Frankenstein.

TheoFantastique: I often begin my interviews on a personal note to find out more about the individual and why their areas of expertise connect with them so passionately. What is your personal interest in the Frankenstein myth? How did you get involved in researching and writing about it and how does it connect with you personally?

Susan Tyler Hitchcock: I have for decades been drawn in by a fascination with the personalities of English Romantic literature. I studied English literature and wrote a PhD dissertation on Percy Bysshe Shelley. My last book was Mad Mary Lamb, about the early 19th-century children’s author Mary Lamb who, with her brother Charles, wrote the famous Tales from Shakespeare. In the 1980s I taught literature and humanities to engineering students at the University of Virginia. One day (it happened to be October 31) I was teaching Frankenstein in a course called “Man and Machine: Images of Technology in Literature.” To get the conversation rolling, I wore a dime-store monster mask — bright green, red gashes, bolts in the neck — and we talked about how different the current image of Frankenstein is from the novel itself. That was the beginning of my quest to understand how we got from there — a novel written by an English teenage girl in 1816 — to here — an icon recognized the world around in the 21st century.

TheoFantastique: It might be helpful to sketch a little of the history of Frankenstein for readers to set the context for your book and our discussion. Can you summarize the circumstances concerning the two main facets of the myth that helped birth it and make it grow, Mary Shelley’s story and the 1931 Frankenstein film with Boris Karloff?

Susan Tyler Hitchcock: Wow. How about I write a book about it?

Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, not yet married to Percy Bysshe Shelley, went with him (a married man and a father) and her stepsister, Claire Clairmont, on a quest for poetry, meaning, and Claire’s lover, Lord Byron, to Geneva, Switzerland, in June 1816. Byron had just exiled himself, leaving behind a wife and child, and was traveling with a companion and doctor, John Polidori. The five would gather in the Villa Diodati, a 200-year-old estate house overlooking Lake Geneva. They read ghost stories, and Lord Byron (so Mary Shelley tells us years later) challenged his friends to write stories equally scary. From that challenge arose two finished works: Polidori wrote a novella, The Vampyre, which was the first English vampire story and certainly an inspiration for Stoker’s Dracula, written some 80 years later; Mary Godwin (soon to be Shelley) began Frankenstein. Her novel was published in 1818. It was just another pulp Gothic novel to the publisher — it soon went out of print — but its story so captured the imagination that it was instantly adapted to the stage in Europe and America and reprinted in a “Standard Novel” series in 1831. By the end of the 19th century, most considered the novel a classic of literature. Many works of literature refer to it and spin off from it. Thomas Edison’s silent film company created a 20-minute Frankenstein in 1910. But the watershed event, the reason we all know the monster so well, is the 1931 Universal film starring Boris Karloff as the unnamed man made by man. That film, followed in the coming years by Bride of Frankenstein and Son of Frankenstein — all three starring Karloff as the monster — struck deeply into the world’s psyche. The Universal film series was continued with others playing the monster, the story was retold in numerous other film and dramatic adaptations, and cartoons, comic books, television shows, and other pop media kept him alive to the present day as well.

TheoFantastique: How did the myth move beyond the 1930s horror films of Frankenstein, Bride of Frankenstein and Son of Frankenstein in the decades following to embed itself in the culture so deeply?

Susan Tyler Hitchcock: The myth was already deeply embedded in culture by the time of the 1930s movies, as a matter of fact. For example, in early 1931, before the Karloff film came out, two different economists used the myth of Frankenstein as a way to express their concerns over what they considered a monstrous legal entity emerging onto the scene: the corporation. But the films certainly secured a look for the monster — the flat-topped head, sunken cheeks, bolts in the neck, drab suit too small, elevated shoes — and a certain character for the monster. Karloff’s monster grunts and is awkward; Shelley’s monster spoke eloquently and was nimble. Karloff’s monster also arises as evil from the start, remember: he is implanted with a criminal brain. In Shelley’s novel, the creature is formed capable of intellect and love, but his feelings of being abandoned by his maker and scorned by society evoke violence and hatred in him. What all this means is that when the Karloff monster became the prevailing representative of the Frankenstein myth — and, even more so, during the subsequent Universal and Hammer films retelling the story for a broader public — the moral message of the myth got solidified and, I would say, dumbed down.

TheoFantastique: One of things you discuss in chapter 7 struck me when you wrote:

“After his third Universal film, though, Boris Karloff never again played the monster in a feature film, despite scores of Frankenstein movies made after 1939. In his view, he was not the one abandoning the monster; the producers and scriptwriters were. They wanted a flat, unidimensional character — a clown, to use his expression — while he saw a figure full of contradictions, moral qualms, love and hate, good and evil, hope and despair. His monster embodied the existential loneliness and uncertainty of the twentieth century. ‘The most heartrending aspect of the creature’s life,’ believed Boris Karloff, ‘was his ultimate desertion by his creator. It was as though man, in his blundering, searching attempts to prove himself, was to find himself deserted by his God.'”

Karloff’s thoughts on the creature and its relationship with his creator seem rife with cultural and theological possibilities for reflection. Do you think in ways the Frankenstein myth has been so popular is that many times it reflects a modern existential angst about abandonment by God in terms of questions surrounding the viability of traditional religion in the West, or am I reading too much into Karloff’s thoughts and its possible ramifications?

Susan Tyler Hitchcock: Actually, these meanings can be found all the way back in the novel itself, and no, I don’t think you are reading too much into the novel or into the James Whale-Karloff interpretation of it. Bride of Frankenstein is the film that most clearly shows how James Whale, the director, was fascinated by the religious meanings implied in the story of Frankenstein. Watch that film again with an eye to the references to Christianity. When the monster befriends the old blind man and lies down for his first night of sleep in a human bed, a crucifix hangs, glowing, on the wall above — a suggestion that this is a moment of Christian charity and human kindness. When the monster is chased out of that place of safety, he crashes through a graveyard, angrily pushing over tombstones. When the mob grabs hold of him, they lash him to posts and lift him up, his arms stretched out, as if he is crucified. Bride of Frankenstein, much more than Whale’s earlier Frankenstein, also has a thoroughly evil character: Dr. Pretorius, who convinces Dr. Frankenstein to create a female — an enterprise that literally explodes in his face.

TheoFantastique: In chapter 10 you discuss scientific developments in genetics and how the novel has been attached to debates on this topic so much so that people have expressed fears about “Frankenfoods.” You write that, “Scientists live and operate within a larger world of culture, and the myths that shape that world exert an influence on their beliefs, fears, and aspirations.” How does the Frankenstein myth serve as positively as a mythic foil in contemporary debates like those over genetics and cloning?

Susan Tyler Hitchcock: By the time we were seriously discussing the issues of genetic engineering and cloning in the public forum, Frankenstein had lost its ambiguities and was received by most as having a unified message: Don’t mess with Mother Nature; don’t play God; don’t dare to overstep the limits of knowledge established by the status quo. My belief is that that is not what Mary Shelley originally had in mind when she wrote the novel, but it is what we have made of her story. So Frankenstein has become a code word for the idea that any effort to create life is going to make a monster that will haunt and ultimately destroy us. It’s an easy way to express the conservative argument against scientific experimentation in realms that are new and unknown, particularly those having to do with the manipulation or creation of life-forms.

Susan Tyler Hitchcock: By the time we were seriously discussing the issues of genetic engineering and cloning in the public forum, Frankenstein had lost its ambiguities and was received by most as having a unified message: Don’t mess with Mother Nature; don’t play God; don’t dare to overstep the limits of knowledge established by the status quo. My belief is that that is not what Mary Shelley originally had in mind when she wrote the novel, but it is what we have made of her story. So Frankenstein has become a code word for the idea that any effort to create life is going to make a monster that will haunt and ultimately destroy us. It’s an easy way to express the conservative argument against scientific experimentation in realms that are new and unknown, particularly those having to do with the manipulation or creation of life-forms.

TheoFantastique: Given the prevalence of the myth on a popular level I was surprised to read about the novel’s slow acceptance as a significant piece of English Romantic literature. Why do you think it has a history of negative reception, or at least being overlooked by scholars? Is it the taint of the horror genre? How has this situation changed more recently among scholars?

Susan Tyler Hitchcock: Up through the 1970s, Frankenstein was considered pulp fiction written by a minor female author. I know, because I was a graduate student in English in the 1970s, and I had to justify my putting the novel on my doctoral reading list. These days, every graduate student in English has studied the novel many times over. The change came thanks to changing values in the scholarly world. Feminism swept the academic world in the 1970s, as did a new regard for popular culture as worthy of scholarly attention. 1974 was a watershed year for Frankenstein in the universities. That year, Donald Rieger published Mary Shelley’s original 1818 edition of the novel, with an introduction that explored how she had changed her novel between its original publication and its revision 13 years later. That year was also the publication date of a collection of essays, The Endurance of Frankenstein, that included the classic feminist essays “Female Gothic” by Ellen Moers, which used Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein as a key representative to discuss the special kind of Gothic novel written by women during the late 18th and early 19th century. Today, Frankenstein and Mary Shelley are now on everyone’s reading lists, from public high schools to the top graduate schools. And there are even easy-reader versions of the novel, not to mention all the picture books that use the monster as a lovable character.

TheoFantastique: In chapter 11 you discuss the monster and its myth in contemporary society. This has been expressed broadly in everything from Frankenberry cereal (which I had to pick up for the Halloween season) to Tim Burton’s film Frankenweenie. One of the more popular and iconic images of the monster comes from Boris Karloff as the creature in the Universal films. One of the more emotionally charged discussions in this chapter looked at copyright issues over the image as it relates to Universal and the Karloff family. Can you speak to that briefly?

Susan Tyler Hitchcock: In 1993 four of the children of the Universal horror monsters met at a monster show: Sara Karloff, Bela Lugosi Jr., Ron Chaney, and Dwight Frye Jr. Lugosi is an intellectual property lawyer in California who had already made inroads into protecting the rights of heirs to the characters that their deceased parents created. He encouraged his newmade friends to work together and approach Universal Studios about their ownership of their parents’ monster looks. The heirs won out of court, and in Sara Karloff’s case, she won the rights to ownership not only of the Frankenstein monster but also the Mummy, both of which her father created for Universal. For a while there was a cordial business relationship, with realistic art portraying the monster and tagged with copyright not only to Universal but also to Karloff Enterprises. Then Sara Karloff learned that Universal was bypassing her in business arrangements, so she sued again — and won again. So what has Universal done? They have had illustrators redraft their official portrayals of the key Universal monster — the Frankenstein creature and Dracula particularly — so they no longer look like the movie originals, and so Universal can license the images without sharing the wealth with the heirs.

TheoFantastique: Two of the facets I really appreciate about your book given my background is its cultural and theological aspects (not to mention the mythic). These come together at the close of chapter 11:

“At its heart, Frankenstein speaks of an eternal conflict in the human condition. It is the tension between what we have and what we desire, between that which is firmly within our grasp and that which we can dream but not materialize. The story summons the universal dialogue between what our culture now calls red and blue, conservative and liberal, traditional and progressive, authoritarian and libertarian, conservative and radical.”

Shortly later you draw the chapter, and the book, to a close by stating:

“It was inevitable. Someone was going to slip back into the garden [of Eden] and pick fruit from the other tree [the Tree of Life in addition to the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil]. That is the story told in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Surrounded by talk of poetry, atheism, and science, the imagination of this unmarried teenage mother in the early nineteenth century tapped into a mythic realm where a story had been standing, unplucked, for hundreds of years. She dared to approach the forbidden, ignoring conventional laws of good and evil; she went to the heart of the matter, to the secret of life. She wrote the story humankind had to have been waiting to hear and, having written it, sent it out in the world — her ‘hideous progeny,’ as she famously called it — to be heard, read, enacted, viewed, remembered, retold, analyzed, and interpreted.”

It would seem that as the Frankenstein myth continues to tap into our deepest mythic reservoirs and touches us on personal levels, so much so that like Victor Frankenstein we are repulsed by what we see, but at the same time we can’t look away because in the creature we see our reflection. Would you agree?

Susan Tyler Hitchcock: It is amazing that this book and its story continue to fascinate us. Given how much it has been retold, turned into comic books and caricatures, simplified and misinterpreted, you would think the myth would have died. But it is still electric with meaning. Every Halloween season new interpretations — local and international — come onto the scene. I am thrilled to read that Guillermo del Toro, the director who created Pan’s Labyrinth, is at work on a film version of the story. And I am equally thrilled whenever I read of a local radio or stage interpretation. Every time we retell or reexperience the story of Frankenstein, we delve deeper into our own beings, asking the eternal questions: Is it better to risk everything in order to venture out into the unknown, or is it better to stay safe and not push the limits of our knowledge? Am I an angel or a monster? . . . or am I, as I hear Mary Shelley suggesting, a bit of both?

TheoFantastique: Susan, your book is a great read, and it provides an important dimension of consideration for fans of the Frankenstein myth. Thank you for the tools that enable an interesting exploration.

Susan Tyler Hitchcock: I always love sharing my thoughts about my favorite monster. Thank you.

3 Responses to “Susan Tyler Hitchcock: Frankenstein: A Cultural History”