Following is the second installment of the interview with Douglas Cowan, sociologist of religion at Renison University College, who discusses science fiction and transcendence in connection with his book Sacred Space (Baylor University Press, forthcoming). (Photo to the left is by Chris Hughes and copyrighted by University of Waterloo, Graphics.)

Following is the second installment of the interview with Douglas Cowan, sociologist of religion at Renison University College, who discusses science fiction and transcendence in connection with his book Sacred Space (Baylor University Press, forthcoming). (Photo to the left is by Chris Hughes and copyrighted by University of Waterloo, Graphics.)

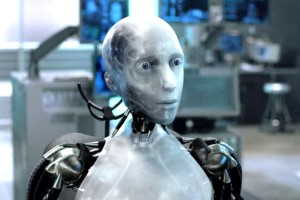

TheoFantastique: One of the areas of research I find interesting is techno-theology, a theological exploration of our relationship with technology. As computers, artificial intelligence, and robotics become more advanced this pushes the boundaries of our conceptions of ourselves and what it means to be human. How have aspects of science fiction such as Star Trek: The Next Generation with its Commander Data, and the film I, Robot, explored transcendence in this context?

Doug Cowan: Well, I think first of all we need to abandon (or at least deemphasize) the question of “what it means to be human” as the benchmark of meaning and value. Of course, I’m not the first to suggest this by a long shot, but it is implicit in much of science fiction cinema and television. All too often, “human” is a slippery synonym for “like us,” especially given the numerous historical examples in which dominant cultures have labelled non-dominant ones “sub-human,” and when something is not “like us” we seem to feel we have license to treat it less than “humanely.” Consider, for example, Sarah Connor’s voiceover at the end of Terminator 2: Judgment Day (which, in my opinion, should have been the end of the franchise, it was that good): “The unknown future rolls toward us. I face it for the first time with a sense of hope. Because if a machine, a Terminator, can learn the value of human life, maybe we can too.”

That said, usually, the relationship between humans and machines is considered solely from our point of view, and arguably, in the vast majority of cases, this is entirely appropriate. If my toaster goes on a rampage, I want it stopped. Now. When we are the victims of technological malfunction or the intended targets of mechanical malfeasance, the machines are defined as defective or evil (or possibly both). HAL in 2001: A Space Odyssey is a good example of this—though I argue that HAL is anything but evil. As long as machines meet the needs for which we created them, then all is well. If, for whatever reason, the understood economy between creator and creation shifts, few films leave any doubt that the latter must be terminated in favor of the former. As more than half a century of science fiction cinema (especially in its science fiction–horror hybrid) makes clear, in the balance between humanity and technology the scales must always tip in our favor. A number of films, however, suggest that the issue is not quite so clear-cut as this, not quite so obviously androcentric as we might like. These films ask us to imagine the question of transcendence from a rather different point of view.

Star Trek: First Contact is one of my favorites in the film series and it is among the most multifaceted, much of it turning on various metaphors of touch and sensation, of boundaries and evolution both achieved and denied. Indeed, First Contact illustrates three broad variations on the question of transcendence and artificial lifeforms. First is the issue of robotic consciousness. How far can it evolve and into what? What are the criteria we should use to determine whether something is a lifeform and what does that imply for the relationships into which we enter? After all, in the film Picard is prepared to sacrifice himself to the Borg collective in order to save Data—a human willing to die, essentially, for a machine. Second is the creation or modification of life “in our own image.” What happens when we create new life, not from neural nets and positronic matrices, but by manipulating our own cells, our own selves? What responsibilities do we have to those creatures that evolve in the laboratory under our often less-then-tender mercies? These are the questions that are raised in films such as The Island or Blade Runner. Are they simply organic material that we are free to use as we please, or does the potential for a separate consciousness demand the freedom and protection of a separate destiny? As the Creature says to Frankenstein in what has become the cinematic icon of the science fiction–horror hybrid, “What of my soul? Do I have one? Or was that a part you left out?” Third, if transhumanism represents the hubristic belief that the synthesis between humanity and machine will inevitably lead to a better, brighter future—a utopic melding of form and function—then the Borg represent the dystopic teleology of that vision. Unlike the tentative ventures into the cyborg represented by The Six Million Dollar Man and The Bionic Woman, in which the essence of humanity remains the touchstone of reality, such characters as Robocop, the Lawnmower Man, Johnny Mnemonic, and the numberless inhabitants of The Matrix suggest that the hope of transcendence is all too often bound by the unseen consequences of our limitations.

Star Trek: First Contact is one of my favorites in the film series and it is among the most multifaceted, much of it turning on various metaphors of touch and sensation, of boundaries and evolution both achieved and denied. Indeed, First Contact illustrates three broad variations on the question of transcendence and artificial lifeforms. First is the issue of robotic consciousness. How far can it evolve and into what? What are the criteria we should use to determine whether something is a lifeform and what does that imply for the relationships into which we enter? After all, in the film Picard is prepared to sacrifice himself to the Borg collective in order to save Data—a human willing to die, essentially, for a machine. Second is the creation or modification of life “in our own image.” What happens when we create new life, not from neural nets and positronic matrices, but by manipulating our own cells, our own selves? What responsibilities do we have to those creatures that evolve in the laboratory under our often less-then-tender mercies? These are the questions that are raised in films such as The Island or Blade Runner. Are they simply organic material that we are free to use as we please, or does the potential for a separate consciousness demand the freedom and protection of a separate destiny? As the Creature says to Frankenstein in what has become the cinematic icon of the science fiction–horror hybrid, “What of my soul? Do I have one? Or was that a part you left out?” Third, if transhumanism represents the hubristic belief that the synthesis between humanity and machine will inevitably lead to a better, brighter future—a utopic melding of form and function—then the Borg represent the dystopic teleology of that vision. Unlike the tentative ventures into the cyborg represented by The Six Million Dollar Man and The Bionic Woman, in which the essence of humanity remains the touchstone of reality, such characters as Robocop, the Lawnmower Man, Johnny Mnemonic, and the numberless inhabitants of The Matrix suggest that the hope of transcendence is all too often bound by the unseen consequences of our limitations.

As TNG fans of the series know very well, Data has in many ways already achieved that which he seeks. Like a Zen Buddhist, he simply needs to realize it. In The Next Generation (and Star Trek: Voyager, in which Seven-of-Nine approaches the problem from the perspective of the Borg), transcendence is not a function of sensation, but of relationship and the reciprocal permeability of the boundaries between those who exist in relationship.

This is also clear in films such as I, Robot. First, the special NS-5 robot Sonny invites us to consider the evolution of consciousness, of personality in artificial lifeforms. Besides the distinction of having a personal name, he stands out in both behavior and self-awareness. He stands apart. “They all look like me,” he says, wondering at the ranks of other NS-5s and articulating a level of apperception never before heard in robots, “but none of them are me.”

This is also clear in films such as I, Robot. First, the special NS-5 robot Sonny invites us to consider the evolution of consciousness, of personality in artificial lifeforms. Besides the distinction of having a personal name, he stands out in both behavior and self-awareness. He stands apart. “They all look like me,” he says, wondering at the ranks of other NS-5s and articulating a level of apperception never before heard in robots, “but none of them are me.”

One way (though not the only way) to evaluate the evolving self-consciousness of a robot as an entity apart from its programming considers its ability to fashion cognitive models of both internal and external worlds, and to understand both the difference and the relationship between those worlds. As consciousness develops and personality individuates, these internal and external models—self and world, as it were—appear increasingly distinct but require increasingly complex and nuanced interaction. What we perceive as “outside” influences who we are “inside,” demanding (and driving) the development of a reflexive autonomy that far exceeds the basic “if, then do” module on which all binary computing—whether human or robotic—is based.

This is most profoundly implicated in the moment of existential crisis, the ability to imagine a world in which one does not exist. So far as we know, death takes most creatures by surprise. If they are aware of it at all, it is in the fleeting moment of its occurrence, not the drawn-out uncertainty of its approach. We, on the other hand, contemplate death; we fear it, avoiding it when we can, preparing for it when we must; we ritualize and fetishize it, doing all we can to ignore its reality and forestall its inevitability. “Will it hurt?” Sonny asks Calvin as she prepares to use nanobots to decommission him, to “kill” him and bring forth a world in which he is suddenly and irrevocably not.

Once again, though, these are not simply questions of filmmaking and storytelling, but have serious implications offscreen. We may not be there yet, but they are issues with which we will need to deal someday. Perhaps someday sooner than many of us think.

TheoFantastique: At a couple of points you draw upon the film Contact in your discussion. In one instance you use it to illustrate human responses to contact with extraterrestrial intelligence. What basic forms have developed in science fiction to the earth-shattering “revelation” that would come with this form of transcendence?

TheoFantastique: At a couple of points you draw upon the film Contact in your discussion. In one instance you use it to illustrate human responses to contact with extraterrestrial intelligence. What basic forms have developed in science fiction to the earth-shattering “revelation” that would come with this form of transcendence?

Doug Cowan: Some would welcome it, others fear it. There are a range of responses. For the more conspiracy minded, there are the variety of pop culture products such as The X-Files which are predicated on the notion that alien contact has already occurred, for good or ill. In terms of the narrowness of theological vision, though, the “Your God is too small” problem of which Sagan spoke, for me the most interesting position is what I call “terracentric human exceptionalism”—Christian fundamentalists who believe that the humankind is the only intelligent life in the universe. Now, there are lots of different people who believe that, but the reasoning behind the argument is fascinating in the breadth of its claims and frightening in the depth of it hubris.

In what I call in the book “the calculus of transcendence” their logic is clear: we know that there are no extraterrestrials because the Bible does not mention them. “Though atheistic scientists would scoff at this,” writes Ron Rhodes, a widely read fundamentalist Christian researcher and writer, “Scripture does in fact point to the centrality of planet Earth and gives no hint that life exists elsewhere.” Earth, he writes elsewhere, is “absolutely unique in God’s eternal purposes.” The logical fallacies inherent in his argument notwithstanding, fellow fundamentalist Bob Larson could not put this more clearly. “While the Bible does not explicitly rule out extraterrestrial life-forms,” he writes, “there is sufficient scriptural evidence that life on Earth was created by God as a special act of divine grace, duplicated nowhere else in the universe. Thus the aliens who contact us cannot be from another planet or solar system . . . Biblical logic then concludes that demons, fallen angels, are the creatures behind legitimate UFO occurrences.” For people like this, the possibility of extraterrestrial life presents an enormous problem—one that is, once again, theological (and, in my view, therefore also sociological).

TheoFantastique: Later in the book you explore various questions related to the reenvisioned Battlestar Galactica series. Unfortunately, I was never able to see much of it since it always drew my wife’s ire given her devotion to the original series of the 1970s! Can you talk a little about the ways in which the second incarnation of Battlestar Galatica explored religion in complex and multifaceted ways?

Doug Cowan: I have to admit I got hooked on the reenvisioned series, though I think it was a three-season story arc that was stretched over four seasons simply because of its massive popularity and the money it was making for the producers. In terms of the storyline of the last season, God may have had a plan for Gaius Baltar, but Ronald Moore, not so much.

Many argue that there are really only two contending faiths represented on the show: a basic polytheism versus a basic monotheism. I suggest that this dichotomy seriously diminishes the potential richness of the series. Put differently, I begin many of the various religious studies courses I teach with some version of the statement, “There is no such thing as ‘Christianity,’” a comment that never fails to draw the ire of at least one student in the class. “Of course,” I respond to their almost inevitable indignation, “there’s no such thing as Buddhism either, or Judaism, or Islam, or Hinduism.” By this point, many students are wondering if they’ve enrolled in the wrong course, but the point is this: there is no one thing that we can definitively call “Christianity”; there are only various and sundry Christianities, religious traditions that can vary dramatically depending where in the world one looks and when, and which are often as different from each other as they are from other religions. Roman Catholicism in the twenty-first century, for example, seems an entirely different religion from that of fifteenth century. And, in many ways, it is.

In the same way, though, there is no such thing as the human religion in the Colonial fleet clustered around Galactica, just as there is no such thing as the Cylon religion, resurrection hub or not. There are only the religions of Battlestar Galactica, and as we have seen in each of the other series we have considered, they reveal themselves most clearly through the people in whom they are embodied.

In the same way, though, there is no such thing as the human religion in the Colonial fleet clustered around Galactica, just as there is no such thing as the Cylon religion, resurrection hub or not. There are only the religions of Battlestar Galactica, and as we have seen in each of the other series we have considered, they reveal themselves most clearly through the people in whom they are embodied.

Many commentators, it seems to me, persist in posing entirely the wrong questions, questions that are either meaningless or unanswerable, both in the context of the series and of religious history and behavior. Noting the utilitarian ends to which both the Cylons and the humans put their respective religions, for example, Bryan McHenry asks, “Is the manipulation of religious beliefs ever justifiable?”—and goes on to interpret Adama’s original deception about knowing the way to Earth as a violation of the American Constitution. Although Ronald Moore, BSG’s creator, admits that “the show is really supposed to be about our society and political structure,” he warns us that relationships are not meant to be “as simple as the Cylons are Al Qaeda and Laura Roslin (the President) is George Bush.”

One certainly hopes not, since the analogy makes very little sense in the context of the “war on terror” waged by the Bush White House since October 2001 and the American invasion of Iraq in 2003, which at this point has resulted either directly or indirectly in more than one hundred thousand civilian deaths. Indeed, though it shouldn’t be necessary, it seems worth pointing out that the Twelve Colonies are not the United States and that the Cylon rout of humankind could arguably sanction any number of extraordinary measures. More importantly, however, the plain and simple fact is that, whether it seems justified or not, religious beliefs are manipulated regularly, often egregiously, to serve a wide variety of ends and agendas—not least by the Bush administration in the prosecution of its putative war on terror. Asking whether the manipulation of religion is warranted, legitimate, or ethically acceptable may be an interesting intellectual exercise, but the question relies on a naïve and simplistic understanding of religion and rings utterly hollow in the context of lived religious practice.

On the other hand, philosopher Taneli Kukkonen wonders, “Are the Cylons and Colonials both justified in their respective faiths? Or do religious believers on both sides merely impose meaning on an otherwise cold and uncaring universe?” Kukkonen’s implicit fallacy of limited alternatives notwithstanding, once again we are back to the problem of evaluation and adjudication: Is this a reasonable religion? Does it make sense? Indeed, as Kukkonen puts it, “Are there independent, rational criteria by which the merits of the two contending faiths can be assessed”? Unfortunately, this is a very common line of analysis, but put simply, “No, there aren’t.

Religion as a social and a human (or, perhaps, Cylon) phenomenon is neither rational nor irrational. It is both, and both rationality and irrationality depend on situation and perspective. What seems eminently reasonable to some—from simple belief in a nonempirical entity to the willingness either to kill or to die at the behest of that entity, or from prayer in the face of personal crisis to belief in the efficacy of that prayer—is for others profoundly irrational. More importantly, while Kukkonen wants to stand on the platform of “independent, rational criteria,” he both introduces and concludes his argument in explicitly theological ways—rational from a certain perspective, perhaps, but hardly independent. According to him, “the Cylon God’s plan seems cruel and inscrutable if it includes the Cylons’ attempt to eradicate humanity.” But inscrutable to whom, and according to what criteria? Is this any more cruel than the commands of the Hebrew God to eradicate various Canaanite tribes when the newly designated chosen people escaped from Egypt and made their way into the promised land? Falling completely into the trap of the good, moral, and decent fallacy, Kukkonen seems to forget that what is one group’s sacred story is another’s hidden history of genocide.

TheoFantastique: In your discussion of The Matrix you note how various commentators have interpreted the film in keeping with their own religious views. Can you share a few examples of how this has taken place, and how might this serve as a reminder about the need to be aware of our interpretive perspectives and biases that influence our interpretations?

TheoFantastique: In your discussion of The Matrix you note how various commentators have interpreted the film in keeping with their own religious views. Can you share a few examples of how this has taken place, and how might this serve as a reminder about the need to be aware of our interpretive perspectives and biases that influence our interpretations?

Doug Cowan: For all its action, intrigue, and dazzling special effects, and for all the commentary it has generated, I suggest that The Matrix is essentially tabula rasa, a blank slate. It’s a visual feast in many ways, but it’s also an empty canvas on which viewers inevitably paint their own understandings of reality, their own perceptions of the quest for transcendence. Contrary to outdated media theories that paint the audience as a collection of passive receivers and filmmakers as the ultimate arbiters of cinematic meaning, The Matrix is one of the best science fiction examples of the fact that what we take away from a film or television experience is inevitably a function of what we bring to it. Movies, as director Joe Dante says, are like Rorschach tests; “there is what you mean when you make them, and then there’s what people get out of them. And sometimes those two things are not always the same.” This is never more true than when we attempt to understand a film such as The Matrix in terms of the varied human quests for transcendence.

“The Matrix resounds with the elements of Jewish and Christian apocalyptic thought,” writes Paul Fontana, a New Testament student at the Harvard Divinity School, “specifically, hope for messianic deliverance, restoration and establishment of the Kingdom of God.” Indeed, Fontana asserts confidently that “anyone with a religious background”—by which we must assume he means either Jewish or Christian—“can notice some of the more obvious Biblical parallels in The Matrix.” There is no guarantee of this, however, as Stephen Prothero’s findings on the appalling lack of religious literacy in America make clear, but others concur, including fellow Christian Mark Stucky, who sees the first film as the “Gospel of Neo” and the two sequels—Reloaded and Revolutions—as the “Acts” and the “Apocalypse According to St. Neo” respectively. “Although various other allusions exist,” Stucky opines, “a major mythological motif in the film and its two sequels consists of blatant and vital references to Christ.”

Lest anyone think that The Matrix is little more than Christian missiology in black leather and bullet-time, however, there are a number of other interpretive options.

Acknowledging the film’s “the messianic motifs,” Buddhologist Paul Ford points out that “the Buddhist parallels in The Matrix are numerous.” “The Matrix itself is analogous to samsara, the illusory world that is not the reality it appears to be”; discipline and control à la the Noble Eightfold Path allow Neo to enter the Matrix as a bodhisattva; and the different characters’ actions demonstrate the balancing effects of karma. Moreover, at the conclusion, “no longer constrained by fear, doubt, or ignorance, Neo, like a Buddha, has transcended all dualities, even the ultimate duality of life and death.” On the other hand, Muslim philosopher Idris Hamid discusses “the Cosmological Journey of Neo” as “an Islamic Matrix,” while Anna Lännström writes about “The Matrix and Vedanta: Journeying from the Unreal to the Real.” Matt Lawrence offers a Taoist interpretation of the films, while Frances Flannery-Daily and Rachel Wagner see in them an unmistakable Gnostic allegory. Reading the films through the Advaitic teachings of the Indian guru Ramana Maharshi, Pradheep Chhalliyil interprets The Matrix trilogy as an elaborate tale of Self-realization.

As you know very well, indeed you’re writing about this for a collection in which I have an essay as well, The Matrix has even found its way into new religious consciousness, and in the years immediately following the trilogy’s release, I received regular emails inviting me to join Matrixism, “the Path of the One,” an online religion that, among other things, makes psychedelics a sacrament, equates pornography with prostitution, and locates the origins of its beliefs nearly a century ago in the public speeches of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, son of the founder of the Bahá’i faith.

In the end, whether you take the blue pill or the red, Morpheus is right: What matters is what you believe.

TheoFantastique: Is there any one major thing that you hope readers come away with from your discussion of science fiction and transcendence?

Doug Cowan: That these are important stories and that they tell us important things about who we are, what we value, and what we hope for.

TheoFantastique: Doug, thanks again for the opportunity to read the draft of the manuscript for Sacred Space, and for making time in a busy academic teaching schedule to discuss the book.

Doug Cowan: Always a pleasure, John.

2 Responses to “Douglas Cowan Interview Part 2: Sci-Fi, Transcendence and “Sacred Space””