Joseph Laycock is an independent scholar and doctoral candidate at Boston University, and author of Vampires Today: The Truth About Modern Vampirism (Praeger, 2009) who was interviewed here in the recent past on this book. He has returned to discuss a paper he submitted to the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion titled “The Folk Piety of William Peter Blatty: The Exorcist in the Context of Secularization.”

Joseph Laycock is an independent scholar and doctoral candidate at Boston University, and author of Vampires Today: The Truth About Modern Vampirism (Praeger, 2009) who was interviewed here in the recent past on this book. He has returned to discuss a paper he submitted to the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion titled “The Folk Piety of William Peter Blatty: The Exorcist in the Context of Secularization.”

TheoFantastique: Joe, as a younger scholar who likely did not see The Exorcist when it appeared in theaters in the 1970s, what is the personal interest in it for you personally and as a researcher in religion and theology?

Joseph Laycock: As I allude to in the paper, I first saw The Exorcist when it was re-released in 2000. I saw the premiere at the SXSW music and film festival in Austin, Texas. I remember there was a bat flying around the theater. (Austin is home to the largest urban bat colony in the world). I sat in the back row and the man sitting in front of me turned out to be William Peter Blatty himself. Afterwards he went before the audience and took questions. There were a lot of film buffs and he seemed slightly annoyed by their inquiries. He must have repeated three times that nothing was meant to be symbolic and that everything in his story was based on actual experience.

I didn’t get around to reading the novel until the summer of 2008, but when I did I immediately wanted to write a paper on it. I think what struck me most was not the supernatural elements but the little things, like a character chanting “Namu Myoho Renge Kyo.” I remember thinking that The Exorcist is a sort of time capsule of what America’s religious landscape looked like circa 1970. Similarly, the description of Father Karras’ crisis of faith and his struggle to reconcile it with his scientific training has an amazing verisimilitude that I thought could only come from actual experience. The final catalyst in starting this project was working with Dr. Jon Roberts of Boston University. Roberts uses The Exorcist in a course on American religious history for the very reasons I’ve described.

TheoFantastique: How influential was The Exorcist both on the original audiences who watched it decades ago, and in the subsequent development of aspects of pop culture?

Joseph Laycock: In the 1970s, The Exorcist was on the New York Times best-seller list for fifty-five weeks. Its commercial success paved the way for Stephen King and other best-selling horror novelists. But it was the film adaptation in 1973 that is most remembered.

A Time article described a line 5,000 people long to buy tickets. And in almost every screening of the film, people would become overwhelmed and have to leave, faint, and, of course, vomit. There are numerous articles from 1973 describing theaters soaked in vomit after showing The Exorcist. The film even appears in the Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, because it was linked to cases of psychosis. It also created a demand for actual exorcisms. Numerous charismatic “deliverance ministries” arose after the film.

Obviously, nothing like that happened when I saw The Exorcist in 2000. Since the re-release you can find Regan’s demonic face covered with vomit grinning at you from T-shirts and even bobble-head toys. The “hipster” culture has been accused of “fetishizing authenticity” as they plunder all of post-war culture searching for fresh artifacts of retro chic. Sadly, I think this has become the fate of The Exorcist. On the other hand, only a handful of horror movies are remembered in this fashion. I think Generation Y has fetishized The Exorcist precisely because they can sense its authenticity.

Obviously, nothing like that happened when I saw The Exorcist in 2000. Since the re-release you can find Regan’s demonic face covered with vomit grinning at you from T-shirts and even bobble-head toys. The “hipster” culture has been accused of “fetishizing authenticity” as they plunder all of post-war culture searching for fresh artifacts of retro chic. Sadly, I think this has become the fate of The Exorcist. On the other hand, only a handful of horror movies are remembered in this fashion. I think Generation Y has fetishized The Exorcist precisely because they can sense its authenticity.

TheoFantastique: Can you sketch the ways in which the film has been interpreted critically and how this contrasts with your own interpretive approach?

Joseph Laycock: Relatively little has been written on the novel, but volumes have been written on the film. One thing I noticed was resistance to the idea that this could actually be a story about religion. Numerous theorists (including Stephen King) have read possession as code for something else that we fear either consciously or sub-consciously. According to most film theorists, The Exorcist is actually about fear of the counter-culture, fear of children, fear of women, etc. Conversely, many critics who thought The Exorcist was actually about demonic possession found it distasteful. S.T. Joshi, for instance, characterizes Blatty as a Catholic evangelist and The Exorcist as a sort of hellfire sermon.

While psychoanalytical readings are interesting, I don’t believe they can explain the behavior of audiences watching The Exorcist in 1973. I think those reactions can be attributed to a very literal fear of demonic possession. Furthermore, I think these readings of the film point to a disconnect between popular religion and the idea of secularization. The secularization narrative is so powerful, that even when audiences are fainting from terror while watching The Exorcist, it is assumed that this is the catharsis of some repressed and previously unknown fear, rampant in our collective subconscious, because the idea that modern Westerners could actually be afraid of the devil seems an impossibility.

TheoFantastique: How might The Exorcist reflect author William Peter Blatty’s life experiences?

Joseph Laycock: Blatty has described himself as a “relaxed Catholic” and his spiritual life is reflected in both the Catholic character Father Karras and the secular character Chris MacNeil. Like Karras, Blatty was raised by his mother in extreme poverty and was extremely troubled by her death. He attended Georgetown University, a Jesuit school, which serves as the setting for The Exorcist. Blatty suffered the same doubts as Father Karras and described a longing for a miracle that might shore up his faith. This “miracle” came in 1949 when a story appeared in The Washington Post about a boy from Mount Ranier, Maryland who had become possessed and been successfully exorcised. Blatty had already heard rumors of the exorcism through the Jesuits and successfully tracked down the exorcist. However, he would not begin writing his novel for another twenty years. After Georgetown, Blatty learned Arabic and worked for the US Information Agency in Beirut. His time in the Middle East became the inspiration for the opening scene of The Exorcist in Iraq.

Joseph Laycock: Blatty has described himself as a “relaxed Catholic” and his spiritual life is reflected in both the Catholic character Father Karras and the secular character Chris MacNeil. Like Karras, Blatty was raised by his mother in extreme poverty and was extremely troubled by her death. He attended Georgetown University, a Jesuit school, which serves as the setting for The Exorcist. Blatty suffered the same doubts as Father Karras and described a longing for a miracle that might shore up his faith. This “miracle” came in 1949 when a story appeared in The Washington Post about a boy from Mount Ranier, Maryland who had become possessed and been successfully exorcised. Blatty had already heard rumors of the exorcism through the Jesuits and successfully tracked down the exorcist. However, he would not begin writing his novel for another twenty years. After Georgetown, Blatty learned Arabic and worked for the US Information Agency in Beirut. His time in the Middle East became the inspiration for the opening scene of The Exorcist in Iraq.

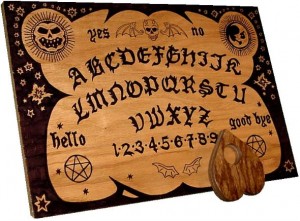

Chris MacNeil and her family are based directly on the actress Shirley MacLaine who was once Blatty’s neighbor. MacLaine was an actress and single mother with a young daughter. MacLaine’s French housekeepers were also turned into characters, as was the British director J. Lee Thompson. Although MacNeil is not religious she experiments with a variety of spiritual practices, including using a Ouija board “to access her unconscious.” In fact, Blatty used a Ouija board after the death of his mother and, according to MacLaine, once organized a séance at her house.

TheoFantastique: Can you describe secularization theory and how The Exorcist would seem to counter this in your thesis regarding folk piety?

Joseph Laycock: There are two versions of what has been called, “The cultural myth of universal secularization.” In one version, belief in the supernatural is unable to compete with scientific rationalism: Accordingly, religion will be forced to renounce supernaturalism or else die out. In another variant, religion will continue to exist but only as a very private phenomenon with no social or political significance. While both these trends have occurred in Western culture, most sociologists of religion now agree that any sort of universal secularization is unlikely to happen anytime soon.

However, the secularization narrative carried a lot of weight when Blatty was writing his novel. The Exorcist was written in 1969, three years after Time magazine ran its famous cover asking “Is God Dead?” A Gallup poll taken in January 1970 indicated that 75 percent of survey respondents felt religion was losing influence. This is the highest percentage ever recorded since Gallup began this poll in 1957. I argue that by simply showing the religious elements from his own life-world in his novel, Blatty created a counter-narrative to the myth of universal secularization. I also think that this critique is part of the appeal of The Exorcist. For people who wanted to believe in demons, The Exorcist gave them permission to do so even if the intellectual elite didn’t.

The Achilles’ heel of the secularization narrative is folk piety. Folk piety, or popular religion, is distinct from ecclesiastical religion, the official doctrines of the church. Since the Protestant Reformation, the Catholic Church has been forced to take an increasingly guarded position about the supernatural. Issues of exorcism and the demonic in particular, are often regarded as a source of embarrassment by the modern church. This trend would seem to support the idea of universal secularization. However, supernaturalism lives on in the form of folk piety. The Exorcist portrays numerous examples of supernaturalism and the fantastic from American folk piety such the belief in demons, the use of Ouija boards, parapsychology, and rumors of Satanic cults.

The Achilles’ heel of the secularization narrative is folk piety. Folk piety, or popular religion, is distinct from ecclesiastical religion, the official doctrines of the church. Since the Protestant Reformation, the Catholic Church has been forced to take an increasingly guarded position about the supernatural. Issues of exorcism and the demonic in particular, are often regarded as a source of embarrassment by the modern church. This trend would seem to support the idea of universal secularization. However, supernaturalism lives on in the form of folk piety. The Exorcist portrays numerous examples of supernaturalism and the fantastic from American folk piety such the belief in demons, the use of Ouija boards, parapsychology, and rumors of Satanic cults.

Today, sociological data suggests that the America Blatty presents in The Exorcist is accurate. While ecclesiastical religion may frown at talk of demons, we have numerous polls indicating that many Americans do believe that angels and demons are active in the world. Furthermore, these beliefs are not always private but are continually leaking into the political sphere. One example of this comes from a research report on a Christian picket of pornography. 98 percent of the picketers reported a belief in an active personal “transcendent” force of evil that was directly involved in pornography. Another example is Louisiana Governor Bobby Jindal, who has openly described his participation in an exorcism. Clearly, supernaturalism is in no danger of disappearing anytime soon.

TheoFantastique: One aspect of disenchantment that I find intriguing, and which I wish more ecclesiastical authorities would become aware of, is Weber’s idea that you discuss in your paper wherein “church apologists had a hand in bringing about ‘the disenchantment of the world’ as they defended their doctrines through rationalization, banishing the supernatural to an increasingly transcendent role.” Doesn’t this mean that ecclesiastical authorities have to walk a fine line in late modernity in seeking both rationality and a level of enchantment?

Joseph Laycock: Weber argues that church apologists were forced to “rationalize” their doctrines or else be accused of superstition. So in ecclesiastical religion, the supernatural became increasingly less immanent and more transcendent. These changes made religious doctrine more resistant to the critiques of rationalists, but they also made religion less meaningful to practitioners.

The process of disenchantment can be seen quite starkly in the Christian tradition of exorcism. There are virtually no demons at all in the Hebrew Bible. By contrast, the world of the New Testament is full of demons. Christians have the power to cast them out and, in their own way, demons affirm that Jesus is the messiah and that God is immanent in the world. It seems that the early Christian church had a rich tradition of exorcism. Early writings suggest that Pagans sometimes went to Christians for exorcisms, and this may have furthered the spread of Christianity.

This changed after the Protestant Reformation, which Weber cites as a seminal moment in the history of disenchantment. Exorcists were accused of being in league with the demons (a similar accusation is made against Jesus in the Gospel of Luke). Not wanting to lose face in front of their Protestant critics, Catholic authorities began to regulate who could perform an exorcism and to consolidate what had been essentially a folk tradition into the formal rite of exorcism that appears in the Ritual Romanum, written in 1614. (A passage from this text appears in the novel).

With the rise of medical science, exorcism became even more regulated and increasingly deferential to scientific authority. While the church has not denied the reality of possession entirely, the criteria for a case of genuine possession are now so demanding that an official exorcism is nearly impossible to obtain in developed countries. Of course, rationalism is not necessarily a bad thing, but it has left many Catholics dissatisfied. Those seeking an exorcism now frequently turn to groups that have splintered from the Catholic Church or to charismatic Protestant movements.

For Weber, there was no happy medium to be found: We can either stubbornly cling to supernaturalism, or we can stoically choose the path of rationalism and disenchantment. Both reactions can be found among American Catholic clergy and The Exorcist actually exasperated these differences. I think that the ad hoc solution lies in the division of labor between ecclesiastical religion and folk piety: The church can worry about reconciling religion and reason, while the lay people are free to pursue meaning through supernaturalism. In some cases, Catholic clergy have arranged “under the table” exorcisms in order to maintain this division of labor.

TheoFantastique: How is folk piety expressed through the rite of exorcism and ouija boards in the film and its cultural context?

TheoFantastique: How is folk piety expressed through the rite of exorcism and ouija boards in the film and its cultural context?

Joseph Laycock: Ouija boards were incredibly popular when Blatty was writing The Exorcist. There was also a Ouija board connected to the Mount Ranier exorcism. Structurally, using a Ouija board is very similar to conducting an exorcism. Both activities involve calling out, engaging, and then dismissing a supernatural being and they are both regarded as perilous endeavors. Not surprisingly, the Catholic Church has attempted to control both practices. A campaign to warn American Catholics about the spiritual dangers of Ouija boards was launched as early as 1918.

Blatty seems to have experimented with Ouija boards for the same reason he was interested in exorcisms: He wanted a direct experience of the supernatural that ecclesiastical religion could no longer provide. I think that most people who are interested in these activities have similar motives.

TheoFantastique: You conclude that The Exorcist “fueled a resurgence of folk piety” for audiences of the 1970s. How might contemporary films that touch on the demonic, particularly in the context of apocalyptic, serve the same function in our time?

Joseph Laycock: Millennial expectations are often not amenable to established religious institutions. In 2006 Pope Benedict XVI commented that the Book of Revelation is not about imminent catastrophe but the struggle of Christian churches in Asia in the first century. Benedict’s historical-critical reading still has a message that is relevant for modern Christians, but it makes poor fodder for charismatic religious movements or Hollywood movies. Recent apocalyptic films like Knowing and the upcoming Legion draw on folk piety rather than ecclesiastical religion. These films take a few elements from the Christian tradition and combine them with occultism, extra-terrestrials, and fears of planet-wide disasters. The result is a supernatural story that seems somehow both strange and familiar.

Joseph Laycock: Millennial expectations are often not amenable to established religious institutions. In 2006 Pope Benedict XVI commented that the Book of Revelation is not about imminent catastrophe but the struggle of Christian churches in Asia in the first century. Benedict’s historical-critical reading still has a message that is relevant for modern Christians, but it makes poor fodder for charismatic religious movements or Hollywood movies. Recent apocalyptic films like Knowing and the upcoming Legion draw on folk piety rather than ecclesiastical religion. These films take a few elements from the Christian tradition and combine them with occultism, extra-terrestrials, and fears of planet-wide disasters. The result is a supernatural story that seems somehow both strange and familiar.

Tonight I saw Paranormal Activity, which (spoiler alert!) I think is actually a re-telling of the Book of Tobit. So far this film has grossed over $48 million and seems destined to be a cult classic. It may be the closest thing the millennial generation will ever have to The Exorcist. As the title suggests, it derives its plausibility more from fringe science than from Catholic tradition but the same elements are there including demonology and the ubiquitous Ouija board. Although no one vomited, as the credits rolled someone shouted, “That was the scariest movie I’ve seen in my life!” What is interesting is that the events on the screen were not scary. Most of the shrieks and gasps were in response to things as mundane as thumps or a door slamming. These elements are frightening because of what Julia Kristeva calls “intertextuality.” Regardless of their religious affiliation, the audience knew from folk piety what a door slamming at 3 AM signifies. It this knowledge, and the belief that such things might actually happen, that makes the slamming door scary.

Obviously, a film like Paranormal Activity could not have been created, let alone frightening, if there was not already widespread interest in investigating the paranormal. But it is also likely that in response to this film more people will discover their houses are haunted, conduct amateur experiments in parapsychology, and report belief in demons on Gallup polls. As with The Exorcist and exorcism, art imitates life and life imitates art.

TheoFantastique: Joe, thanks again for discussing your article. I appreciate your research interests.

Joe:

I’m curious about this comment:

The secularization narrative is so powerful, that even when audiences are fainting from terror while watching The Exorcist, it is assumed that this is the catharsis of some repressed and previously unknown fear, rampant in our collective subconscious, because the idea that modern Westerners could actually be afraid of the devil seems an impossibility.

Are these necessarily incompatible conditions? It seems to me that it’s at least plausible to suggest that “Fear of the Devil” is itself a manifestation of a collective subconscious function. If the idea of a kind of separation between an increasingly rationalized ecclesiastical religion and an increasingly (or, at least, stubbornly) superstitious folk religion is accurate, then I think we’re left with an interesting conundrum: did The Exorcist reinvigorate a Western “Fear of the Devil” that can be identified as being fundamentally separate from some broader subconscious fear, or was the consequence of The Exorcist that this broader subconscious fear was given a form and name (“The Devil”) by people who otherwise would have never named it?

What I am arguing, and what Douglas Cowan argues in Sacred Terror, is that there are no subconscious fears when it comes to religion and horror movies. The Devil has been part of our Western cultural heritage for over a thousand years. If American audiences are frightened by a film about demonic possession, it seems counter-productive to assume they are not literally frightened by demons.

I think that what you are getting is a Jungian reading in which Blatty’s film taps into a dark archetype that is part of the universal human experience. So far as I know, such a film reading has never been done before. It might be an interesting project.

The psychoanalytical readings that I am dissenting from are Freudian, not Jungian. In these readings, our repressed fears are not universal, they are neuroses specific to our culture, i.e. “Americans who raised their children in the 1960s are secretly afraid of their own offspring and so seeing a possessed child frightens them.” Furthermore, I think it would be hard to publish a Jungian reading in film studies precisely because Jung’s ideas defy the secularization narrative.

Hm. If this is the case, then shouldn’t there be a kind of concomitance between “belief in the Devil” and “fear of the Exorcist?” Of course, the Western Cultural tradition isn’t the only one that has a preoccupation with demonic possession–in fact, it’s been in our culture since before major conceptions of the devil were articulated–so there’d be no way to say, “Well, then obviously The Exorcist wouldn’t be scary to, I don’t know, Hindus, because they don’t believe in the Devil.”

But I think that this touches on a problem with evaluating horror movies, which is the (I think mistaken) assumption that something in a horror movie is frightening because the audience is literally afraid of the object of the fear. If that were the case, then there ought to be a clear connection between film-induced fear and fear that’s the product of a literal referent. Like, if I were literally afraid of plane crashes (which I am), I ought to also be afraid of movies about plane crashes (which I am not)–this despite the fact that I know that plane crashes are a real thing that can occur.

Simultaneously, I don’t believe in ghosts, but can still be scared by movies about ghosts. Why is the argument that the Devil, by virtue of its continued historical presence, in a privileged position regarding such fears? That unlike all other literary bogeymen, the fear of the Devil is not a product of the context in which the Devil is presented, but rather the product of an actual specific fear of the Devil that grips people who do and do not believe in it?

Obviously, we could say that even the intellectual elite, who conform to the ecclesiastical tradition of disbelief in demons, may remain subconsciously afraid of it; certainly, it’s true that the Devil has been a part of our cultural history for a long time–but, as I said, possession has been a part of our cultural history for even longer. How do we distinguish between an internalized, socially-inculcated fear in a fictional entity, and a wide-spread subconscious fear that comes from a cognitive structural source?

In terms of whether the audience reactions were the result of “subconscious repressions” or related to elements of folk belief systems, this is a very complex issue.

On the one hand, the film clearly had folk religious effects on the audience upon its initial release. Vatican II and the reforms in the Catholic Church in the years prior to the film’s release had begun a widespread “disenchantment” within Catholicism – removing saints from the Church’s calendar and discouraging/abandoning a wide range of sacramentals, prayer, and ritual practices – and Blatty was most probably confronting this process with his story. The Catholic apologetic element in the film was obvious to many, and I have talked to several Evangelical Protestants in recent years (who otherwise believe in demons) who discourage people from seeing the film, as they consider it a piece of Catholic propaganda.

On the other hand, if the film were only touching upon Catholic folk elements (or even generic Christian ones) it would not have had the large audience that it did, so there was obviously something else going on. I first saw the film a few years after its original release as part of a drive-in double feature. I was about 12 years old at the time (circa 1977) and had grown up in a mostly non-religious home. I only attended church a few times a year for special occasions (Xmas, Easter), and the church my family attended was a very liberal, mainline Protestant group that focused exclusively on world peace and brotherly love, while the most supernatural hymn we ever sang was Kumbaya. I don’t believe I had ever even considered whether the Devil existed or not at the time, and I had certainly never heard a sermon on the topic. And yet, the film scared me in a way that no other film has (and I have seen a lot of horror films). To this day, when I debate in my mind as to the best horror film I have ever seen, I place the Exorcist “off of the table” as it were, for it somehow “feels” to me like it was “more” than a movie; that it was somehow scarier than other films on some kind of “other” level.

I think that Blaylock is on to something when he refers to the visceral reactions that audiences were having to the film. I have always been impressed by the intensity of the emotional reactions to the film – including my own. Perhaps the “repressed subconscious reaction” to the film was actually folk Christian elements that have somehow been ingrained into our worldviews and ways of thinking? Either way, the subject clearly deserves more attention.