I first heard of W. Scott Poole through the Religion Dispatches website that involves scholars interacting with pop culture and religion. Scott wrote an article on Jennifer’s Body that I commented on here, and which attracted a lot of interest at the now defunct HorrorBlips. Scott is associate professor of history at the College of Charleston, and the author of Satan in America: The Devil We Know (Rowman & Littlefield, 2009). After some time, and overcoming a number of challenges, we were able to connect for an interview on the thesis of his book as expressed in American horror and pop culture.

I first heard of W. Scott Poole through the Religion Dispatches website that involves scholars interacting with pop culture and religion. Scott wrote an article on Jennifer’s Body that I commented on here, and which attracted a lot of interest at the now defunct HorrorBlips. Scott is associate professor of history at the College of Charleston, and the author of Satan in America: The Devil We Know (Rowman & Littlefield, 2009). After some time, and overcoming a number of challenges, we were able to connect for an interview on the thesis of his book as expressed in American horror and pop culture.

TheoFantastique: Scott, thanks for writing a great book that addresses an interesting thesis. Can you summarize your thesis for readers as we begin our discussion?

W. Scott Poole: The book is a kind of biography of the American Devil, an examination of how this theological and literary concept (and pop culture icon) has changed over time. I argue that there has been, since the colonial era, an American obsession with Satan and I try to suggest that this obsession comes in part because of a deeply held American belief in national innocence. If you believe the notion of “American exceptionalism,” that the United States is in some sense always the good guy on the world stage, then you desperately need an ultimate villain. Satan has provided that and I hope my readers will be stunned at how prevalent the use of satanic imagery has been by various groups in American society who see him behind ever enemy, foreign and domestic.

The book also asserts that the 20th century was a kind of “satanic century” in the sense that the Devil comes to the fore in both pop culture and popular religious movements. Beginning in the 1960s, and connected with the social dislocations and social anxieties produced in that era, fascination with the Devil became common, especially early on with conservative Christians who began to see his influence throughout the culture.

TheoFantastique: As you discuss your thesis you draw upon aspects of popular culture as illustrations and examples, some of which we will discuss in our interview. What is the relationship between religious faith and popular culture, and how might mythic ideas from aspects of pop culture inform our personal and national narratives?

W. Scott Poole: Clifford Geertz famously said (and I paraphrase) that we are all suspended in webs of meaning. I think scholars have to take into account that these webs include the powerful strand of popular culture.

I see images of the Devil popular religious movements and popular culture as coming out of a common matrix, overlapping and reinforcing one another in all kinds of surprising ways. I think I expected to find that the major story when it comes to pop culture images of the devil and evangelical Christian or Fundamentalist images is that they were at war with one another. What I found was much more interesting…they actually borrow heavily from one another, even when they are claiming to be at war.

Pop culture, in my view, always informs and shapes what we think of as more substantial narratives…whether those be theological or national narratives. I know some believe that the there is little substantive in pop culture, that its very nature is ephemeral. I am struck by how powerful pop culture images are and how they draw strength out of what seems to me to be root paradigms in human cultural and religious experience. The notion of apocalypse has, for centuries, been one of those root paradigms and in the last ten to fifteen years everything from the Left Behind phenomenon to Buffy the Vampire Slayer to the films of George Romero has made use of this imagery, shaped and reshaped it while never getting away from the central questions about death and dissolution of the social and human order it raises.

TheoFantastique: Given the focus of exploration of TheoFantastique I am particularly interested in your discussion of the satanic in film. How significant have cinematic depictions of demonic evil been in influencing the American consciousness?

W. Scott Poole: Films dating from the silent era have played a role in what I see as a kind of satanic cultural revival in the 20th century. Comic devils, horrifying devils, sympathetic devils of one kind or another are so common at the cineplex that I think many moviegoers don’t even notice, or at least are so deluged with demonic beings that they don’t notice what a cultural obsession this is.

While I certainly don’t think all beliefs about the Devil are formed solely by films, I do think that film exists in a dialectical relationship with religious belief. For many Americans, portrayals of the Devil on film act as what Peter Berger might call “plausibility structures,” cultural way stations that reconfirm, or simply add color and texture, to beliefs that have come out of folk traditions and institutional churches.

TheoFantastique: How early does Satan or demonic themes appear in American cinema?

W. Scott Poole: Very early, in the era of the silents. It’s very striking to me that some of the earliest European films dealt with both the devil, such as the 1913 film The Student of Prague. It’s almost a kind of “return of the repressed” to use Freudian language. Supposedly the 18th and 19th centuries had created a post-enlightenment intellectual milieu and yet, filmmakers portray these powerful mythic images the moment that it becomes possible in this new medium. In American film, images of Satan become part of the “vamp” tradition in which the Devil is portrayed as using seductive women to corrupt American domestic bliss (usually portrayed by Theda Bara or Adele Farrington).

W. Scott Poole: Very early, in the era of the silents. It’s very striking to me that some of the earliest European films dealt with both the devil, such as the 1913 film The Student of Prague. It’s almost a kind of “return of the repressed” to use Freudian language. Supposedly the 18th and 19th centuries had created a post-enlightenment intellectual milieu and yet, filmmakers portray these powerful mythic images the moment that it becomes possible in this new medium. In American film, images of Satan become part of the “vamp” tradition in which the Devil is portrayed as using seductive women to corrupt American domestic bliss (usually portrayed by Theda Bara or Adele Farrington).

TheoFantastique: You state that “Turn-of-the-century European (particularly Parisian) fascination with Satanism lay at the roots of the horror film in America.” How was this the case, and how did this then develop into the classic Universal horror films?

W. Scott Poole: I talk a bit about what David Skal describes as the emergence of “satanic chic” in nineteenth century Paris. There was a deep romantic fascination with the Devil and a kind of “literary Satanism” represented by the works of Charles Baudelaire and the work of the Symbolist poets more generally. The infamous Grand Guignol Company, with its theatrical representations of morbid topics and gruesome death enjoyed most of its success on the European continent but still included some of the basic themes that would eventually emerge in American horror films. What I argue in the book about most of the Universal films is that they actually play on some of the basic satanic themes that emerged in Europe, using much of the imagery, while also being careful not to make the Devil into the central monster. Tod Browning’s Dracula is dressed as the Mephistophelean character that stage musicians had evoked (because, remember, popular 19th century magicians often evoked the Devil in their advertising to increase the mysticism and mystery of their acts). The Wolf Man is presented to us as being under a kind of satanic curse (remember that glowing pentagram in his hand). Still, in an America where evangelical Protestantism would go from strength to strength throughout the 20th century, there was a tentative approach to any notion of what we would call “religious horror.”

W. Scott Poole: I talk a bit about what David Skal describes as the emergence of “satanic chic” in nineteenth century Paris. There was a deep romantic fascination with the Devil and a kind of “literary Satanism” represented by the works of Charles Baudelaire and the work of the Symbolist poets more generally. The infamous Grand Guignol Company, with its theatrical representations of morbid topics and gruesome death enjoyed most of its success on the European continent but still included some of the basic themes that would eventually emerge in American horror films. What I argue in the book about most of the Universal films is that they actually play on some of the basic satanic themes that emerged in Europe, using much of the imagery, while also being careful not to make the Devil into the central monster. Tod Browning’s Dracula is dressed as the Mephistophelean character that stage musicians had evoked (because, remember, popular 19th century magicians often evoked the Devil in their advertising to increase the mysticism and mystery of their acts). The Wolf Man is presented to us as being under a kind of satanic curse (remember that glowing pentagram in his hand). Still, in an America where evangelical Protestantism would go from strength to strength throughout the 20th century, there was a tentative approach to any notion of what we would call “religious horror.”

TheoFantastique: Can you provide a few examples of how horror films, in the past and continuing on into the present, have drawn upon Satan as a figure for the demonization of the Other?

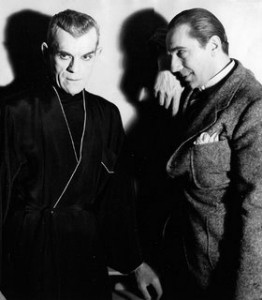

W. Scott Poole: One of the more interesting films from the classic period of the Universal monsters in Karloff and Lugosi in The Black Cat (1934). It’s fairly shocking to me that this film ever gets made in this period since it actually manages to evoke everything from Satanism to incest to necrophilia. American audiences only saw a heavily edited, really heavily censored, version of this film that portrayed Karloff as a satanic grand master of an evil cabal and Lugosi as almost his equally diabolical opponent. What made this possible is that both are portrayed (very easily in Lugosi’s case) as rather diabolical foreigners and the environment they inhabit is a rather decadent European landscape of complete with Bauhaus architecture. The theme that the dark memories of the First World War set off this struggle as something happening “over there”-the foreign Other rather than something in the heart of America.

W. Scott Poole: One of the more interesting films from the classic period of the Universal monsters in Karloff and Lugosi in The Black Cat (1934). It’s fairly shocking to me that this film ever gets made in this period since it actually manages to evoke everything from Satanism to incest to necrophilia. American audiences only saw a heavily edited, really heavily censored, version of this film that portrayed Karloff as a satanic grand master of an evil cabal and Lugosi as almost his equally diabolical opponent. What made this possible is that both are portrayed (very easily in Lugosi’s case) as rather diabolical foreigners and the environment they inhabit is a rather decadent European landscape of complete with Bauhaus architecture. The theme that the dark memories of the First World War set off this struggle as something happening “over there”-the foreign Other rather than something in the heart of America.

Jumping ahead a bit (we will come back, I know, to the late 60s/early 70s) I firmly believe that white, middle class anxieties over the Other helped produce a significant amount of satanic horror in the 1980s. Thoroughly forgettable films like The First Power portrayed the Devil as able to inhabit human bodies and it was the bodies of the homeless and the drug abusers who proved especially susceptible. Even very good films from the 80s like Angel Heart traded in this kind of stuff to a degree, with African folkways and magical traditional portrayed as gateways for the Devil.

More recently, I’ve become interested in how horror in which Satan or the demonic is featured does not only portray women as victims but actually as demonic avatars. To me this, reaches back to some of those silent “vamp” tales I spoke of earlier. I’ve written about Jennifer’s Body in this connection.

The Exorcist deals with some of the same themes though I know we will be talking more about that in a moment.

TheoFantastique: How have horror films like The Exorcist, Rosemary’s Baby, and The Omen drawn upon and informed Catholic and Protestant evangelical conceptions of evil and the satanic in popular culture?

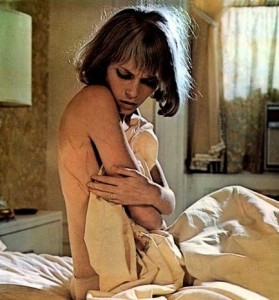

W. Scott Poole: These films are crucial to understanding the place of Satan in both pop culture and popular religion today. All three are products of their particular cultural moment that also tell us something about the direction of American religion and cultural conflict over moral issues. Rosemary’s Baby is, actually, a very subversive document in many ways, telling a story about the efforts of seemingly normal upper middle class people (who are really Satanists) to control Rosemary’s body and force her to bear the antichrist. Often missed is the fact that this narrative is told against the backdrop of Pope Paul VI’s visit to New York, Rosemary’s descriptions of herself as a lapsed Catholic who has married outside of the Church and is not “breeding” like her sisters. Combine all this with the fact that the film appears eight years after the FDA approved Enovin (“the Pill”) and in 1968, the year of the highly controversial papal encyclical Humanae Vita and you have a very interesting window into the emerging crisis in the American Catholic Church.

W. Scott Poole: These films are crucial to understanding the place of Satan in both pop culture and popular religion today. All three are products of their particular cultural moment that also tell us something about the direction of American religion and cultural conflict over moral issues. Rosemary’s Baby is, actually, a very subversive document in many ways, telling a story about the efforts of seemingly normal upper middle class people (who are really Satanists) to control Rosemary’s body and force her to bear the antichrist. Often missed is the fact that this narrative is told against the backdrop of Pope Paul VI’s visit to New York, Rosemary’s descriptions of herself as a lapsed Catholic who has married outside of the Church and is not “breeding” like her sisters. Combine all this with the fact that the film appears eight years after the FDA approved Enovin (“the Pill”) and in 1968, the year of the highly controversial papal encyclical Humanae Vita and you have a very interesting window into the emerging crisis in the American Catholic Church.

The Exorcist has been viewed by some as fairly simplistic Catholic propaganda because it portrays the Church as equipped with the power of exorcism. It really isn’t that simple, on a number of levels. I agree, for example, with a number of horror historians who see it as a comment on the state of the family, a very conservative comment in which a single mother has no idea how to handle her adolescent daughter and relationships cannot be restored, the Devil cannot be cast out, until two representatives from the patriarchal tradition come and fix it. I would also note, as Michael Cuneo says in his book American Exorcism, Protestants as well as Catholics seize on this movie and its imagery as a kind of response to perceived secularization in American society. A wave of fascination with possession and exorcism engulfed American religious life after the film appeared and really continues to this day. Recently, Joseph Laycock has followed up on this discussion in a very fine article that sees The Exorcist as the beginning of a kind of folk religious revival which you have explored with him in a recent interview.

I think The Omen is important as a kind of register for some of the latter part of the 20th century’s obsessions with the coming apocalypse. The Catholic Church figures in this narrative but less as an enemy of the Devil and more as an institution that has been corrupted by him. Some have seen it as a kind of Protestant version of The Exorcist.

It is significant to me that Omen appears around the time that Hal Lindsey’s Late Great Planet Earth purported to forecast the rise of the Antichrist based on a creative reading of the Hebrew and Christian scriptures alongside the daily newspaper. A generation of evangelicals gets their information about the end of the world from a combination of Lindsey and The Omen. This prepares the way for the pop culture juggernaut Left Behind. Of course, all of these materials are drawing on about a hundred years of what scholars of American religion refer to as “premillenial dispensationalism,” an interpretive tradition popular in American Christian Fundamentalism in which the end of human history is understood as a distinct age, preceded by a “rapture” of true Christians that heralds a period of “tribulation” on earth that will include the rise of the Antichrist. While The Omen certainly doesn’t follow this tradition very closely, it borrows significant elements from it.

It is significant to me that Omen appears around the time that Hal Lindsey’s Late Great Planet Earth purported to forecast the rise of the Antichrist based on a creative reading of the Hebrew and Christian scriptures alongside the daily newspaper. A generation of evangelicals gets their information about the end of the world from a combination of Lindsey and The Omen. This prepares the way for the pop culture juggernaut Left Behind. Of course, all of these materials are drawing on about a hundred years of what scholars of American religion refer to as “premillenial dispensationalism,” an interpretive tradition popular in American Christian Fundamentalism in which the end of human history is understood as a distinct age, preceded by a “rapture” of true Christians that heralds a period of “tribulation” on earth that will include the rise of the Antichrist. While The Omen certainly doesn’t follow this tradition very closely, it borrows significant elements from it.

TheoFantastique: As you raise this important topic and then critique the size and role of Satan in American culture, and its popular religion, are you worried that many won’t be able to step back and think reflexively and that you might be seen as watering down the concern for the diabolical, if not in league with it yourself (however unwittingly)? How would you respond to those who might have these concerns?

W. Scott Poole: I do think about this and it actually came up in a public talk I gave Halloween week. I think though that anyone who reads the book will understand that my critique is of a naïve understanding of the nature of evil rather than any effort to try and dilute our conceptions of evil. One of the smartest of the many smart things that scholar Jeffrey Burton Russell said about the idea of Satan is that in the early 1970’s Americans were willing to believe the Devil possessed a teen-age girl but not that he possessed a national government. I point out that in the 1980s, at the same time that “rumor panics” about satanic covens convinced some Americans that most missing children were being kidnapped and tortured by Satanists, millions of children in the US were sinking far beneath the poverty line, living on a nutritional scale similar to developing nations in dangerous neighborhoods gutted by the crack epidemic that was itself a product of a vast and growing inequality of wealth in this country.

So I hope readers will step back and reflect on what “watering down a concept of the diabolical” might really mean. Perhaps you can have a strong, vibrant and even exotic belief in Satan and have a limited, naïve, and simplistic notion of the nature of evil?

TheoFantastique: In your Epilogue you write: “The devil’s greatest trick is not to convince us that he does not exist. It is, instead, to convince us that he lives in our enemies, that he surrounds us, and that he must be destroyed, no matter the cost, no matter the collateral damage. … The devil is the negation and hatred of the Other…” As I reflected on these words I was struck that in 2001 a handful of individuals who were convinced that the United States is the Great Satan committed great acts of violence that led to loss of life, and in response American political leaders were motivated in part by the belief that the attackers were the ones acting as agents of Satan. With this tendency to see the other as diabolical evil while missing one’s own moral blindspots, do you have any suggestions for how we might reflect more self-critically on pop culture as an expression of our dark shadows?

W. Scott Poole: As someone who consumes vast and possibly unhealthy amount of popular culture, I feel very strange saying this but here goes: there has to be a moral and spiritual component to our interaction with pop culture, maybe especially for those of us who love its dark shadows. This does not mean that we cannot have that experience of pure aesthetic enjoyment that powerful narrative provides. But we also have to step back and ponder what we love, not because of a puritanical worrying over what “message” is being conveyed but because it will only increase our love and enjoyment of these things if we make sense of their context and of the many different levels every pop culture document works on.

So, for example, I love The Exorcist. I think it’s one of the great films, in any genre of the 20th century (it would at least be on my top 20 list in fact). At the same time, I hate portions of its message because I have made myself aware of the social and historical context it comes out of. It’s also powerful enough as a work of art that it transcends that context and can be enjoyed in all the complex ways we enjoy any kind of art.

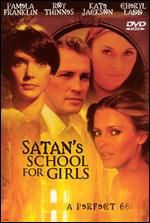

TheoFantastique I was struck in reading a book on television favorites like The Twilight Zone and the many episodes which featured Satan, or growing up in the 1970s and seeing made for television movies like Satan’s Triangle or Satan’s School for Girls. Your book had to limit the scope of discussion, but how might television have been as influential as film, or possibly more, in developing our popular conceptions of Satan and the battle against evil?

TheoFantastique I was struck in reading a book on television favorites like The Twilight Zone and the many episodes which featured Satan, or growing up in the 1970s and seeing made for television movies like Satan’s Triangle or Satan’s School for Girls. Your book had to limit the scope of discussion, but how might television have been as influential as film, or possibly more, in developing our popular conceptions of Satan and the battle against evil?

W. Scott Poole: In my view, made for TV movies often contain even more crude imprints of current cultural obsessions than do film. They are less interesting to me for this reason though they are certainly a part of this flood of interest in the Devil that begins in the late 60s. I have a vague memory of a film from the 80s that was a sort of satanic Stepford wives in which a middle class family discovers that their “perfect suburb” is really run by Satanists. This fed directly off the various conspiracy theories common to that era.

TheoFantasique: You also touch on the unfortunate instances of satanic ritual abuse and satanic panics. Related to this it is worth noting an irony in the case of the West Memphis Three, three teens in the 1990s convicted of allegedly murdering two young boys as they were allegedly influenced by occultism. This case is described in the book Devil’s Knot which is currently being made into a motion picture by director Scott Derrickson, an evangelical who also directed The Exorcism of Emily Rose. Any thoughts?

W. Scott Poole: I would say I touch on the many tragic instances of rumor panics about satanic ritual abuse that were based on various cultural anxieties rather than on any empirical evidence. To me, the West Memphis case is an especially horrible example of this. Here you have three teenagers convicted of a deeply disturbing crime based on little more than the fact that they wore Metallica t-shirts and checked out “occult” books from the library. This, to me, provides an example of how the satanic panic became more than urban legend and ended up destroying lives.

It’s of course interesting that Scott Derrickson will be making a film about this. I actually wonder if it needs a film given the excellent documentaries that have already been produced. Moreover, in Exorcism of Emily Rose, he took an actual case in which a priest had been accused, probably rightly, of negligent homicide in the death of a troubled young woman and raised the question about whether something truly supernatural had been at work. I hope he doesn’t plan the same for the West Memphis case but obviously we will have to see. I hope he makes it a film about the complexities of evil, rather than about visits from the Devil.

TheoFantastique: Scott, again, please accept my thanks for your fine book. I hope it receives the critical and popular attention it deserves.

W. Scott Poole: Thanks, John, for some great questions.

Very interesting interview. My only quibble would be that “American exceptionalism” is sort of the lite, low-cal, secular version of the phenomenon. I think one could make a reasonable argument that within a good number of American strains of what was once Christianity (and is now a sort of American civic folk religion), the United States has supplanted the Church as the Body of Christ and God’s primary, incarnational agency in the world. Satan isn’t just the big-bad supervillain; he’s the Anti-America, a very real power trying to destroy the country because it is in effect indistinguishable from God Himself. It goes a lot deeper than America is always, or at least mostly, a good influence on the world.