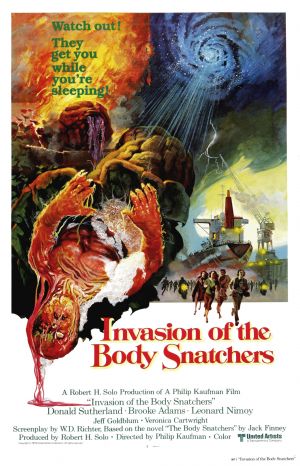

I have been fortunate with the holidays to have a little extra spending cash that I have been able to put into adding to my video library. One of the films added to my collection was Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978). Of course, this film is based on the book by Jack Finney from 1954, and rather than being a remake of the 1956 classic film star Kevin McCarthy, the 1978 version is better understood as a reimagining of Finney’s ideas, shaped to reflect the social and cultural circumstances of the 1970s.

I have been fortunate with the holidays to have a little extra spending cash that I have been able to put into adding to my video library. One of the films added to my collection was Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978). Of course, this film is based on the book by Jack Finney from 1954, and rather than being a remake of the 1956 classic film star Kevin McCarthy, the 1978 version is better understood as a reimagining of Finney’s ideas, shaped to reflect the social and cultural circumstances of the 1970s.

The 1956 film has been interpreted variously as reflecting fears (and paranoia) regarding Communism, and also a critique of social conformity as in the McCarthyism of the time. But Don Siegel, the director of the Fifties film, has offered a very different interpretation:

“Many of my associates are pods, people who have no feelings of love or emotion, who simply exist, breathe and sleep … To be a pod means that you have no passion, no anger, that you talk automatically, that the spark of life has left you … The pods in my picture and in the world believe they are doing good when they convert people into pods. They get rid of pain, ill health, mental anguish. It leaves you with a dull world, but that, my dear friends, is the world in which most of us live.”

Moving to the very different cultural context of the late 1970s, the Philip Kaufman directed version still retains a concern for paranoia and conspiracy, but it does so by interweaving the concerns of people two decades after the original film aired. The location for the 1978 film shifts from a small city to the major metropolitan area of San Francisco, and the concerns of the “me generation” are evident throughout the film. This is especially evident in the depiction of the significance of psychoanalysis as a means of sorting out all of life’s troubles, and (ineffectually) explaining away the growing fears of many in the city by the bay that loved ones and friends just aren’t the same on the inside anymore.

But in viewing the film I wonder if another element might be present that reflects some of the concerns of the time. In the late 1970s the Christian right was a significant force in the culture, particularly but not solely in politics. The general Christian background of America, coupled with the prominence of the religious right, may have contributed to a general background of religious conceptions of the body and the afterlife. It is here that I suggest that Invasion of the Body Snatchers may provide some kind of interaction if not critique.

In one scene near the end of the film, two of the main characters who are still human, Matthew Bennell (Donald Sutherland) and Elizabeth Driscoll (Brooke Adams) are confronted by the alien forms simulating what was once Dr. David Kibner (Leonard Nimoy) and Jack Bellicec (Jeff Goldblum). Kibner encourages them not to resist, and along with Belliceck, describes the benefits of leaving their humanity, and their bodies behind as the pods assume their current identities:

In one scene near the end of the film, two of the main characters who are still human, Matthew Bennell (Donald Sutherland) and Elizabeth Driscoll (Brooke Adams) are confronted by the alien forms simulating what was once Dr. David Kibner (Leonard Nimoy) and Jack Bellicec (Jeff Goldblum). Kibner encourages them not to resist, and along with Belliceck, describes the benefits of leaving their humanity, and their bodies behind as the pods assume their current identities:

David Kibner: “You will be born again into an untroubled world, free of anxiety, fear, hate…

Matthew Bennell: “David, you’re killing us!”

Jack Bellicec: “That’s not true. David’s right. Your minds and memories will be totally absorbed. Everything remains intact.”

I suggest that this segment of dialogue raises philosophical and religious questions about the nature of identity, consciousness and the body, and also Christian conceptions of the afterlife. Some may question my religious reading of this scene, but it would seem that the use of the phrase “born again,” a popular one in the religious right of the time where even President Jimmy Carter claimed to be a “born again Christian,” as well as the the immediate context for the term in reference to the type of world that Bennell and Driscoll are about to enter, permit a reading of religious implications in the scene. In addition, later in the film, after Bennell and Driscoll escape and find a moment of refuge from their alien pursuers, Bennell leaves Driscoll momentarily to track down the source of music he hears in the background. The music is coming from a radio found on a ship at a loading dock putting thousands of pods on board for exporting around the world, and the tune is “Amazing Grace” played on bagpipes. Of course, “Amazing grace” is a very popular Christian hymn, and a variation of this music is found later in the film at its pessimistic climax. The reader can watch the trailer for the film below and hear this music played at the conclusion of the promotional material. It is interesting to read some of the comments from YouTube where one individual shares that this is “an unusual song” to include in this kind of film. Indeed, unless some kind of commentary and critique were being offered of a theological nature related to the cultural context of the time.

Regardless of whether a direct reference is made to critique of aspects of the religious right, this film does provide an opportunity for theological reflection. Two items are in view in the dialogue reproduced above. First, the alien pods offer entrance into a trouble-free world without the struggles and pains connected with our present existence. While this may sound appealing, it also involves a life free of positive emotions as well, including love. The alien earth presented in this film echoes Siegel’s “dull world” that he critiqued in the 1956 version of the film, and it may also reflect the lack of appeal for bland depictions of the afterlife found in the religious right of the 1970s, and perhaps in the present time in less-than-robust presentations in Christian fundamentalism and evangelicalism.

Beyond this, the film may also provide for reflection on other aspects of eschatology, in terms of personal identity as it relates to life after death, and specifically the Christian idea of the resurrection of the body. In the dialogue above the human characters are concerned that as the alien pods assume their identities that in essence the aliens are killing them. Not so, argues one of the aliens: “our minds and memories will be totally absorbed. Everything remains intact.” This raises questions about personal identity in relation to the creation of another body, identical to the original in every way, complete with the mind and memories. Scholars of various stripes, including not only theologians, but philosophers and those in religious studies, have wrestled with this issue asking questions that are echoed in this film: “Is it rational to hope for life after death in bodily form? Will it truly be ‘we’ who are raised again or will it be post-mortem duplicates of us? How can personal identity be secured?”

Here in Invasion of the Body Snatchers, I believe we have yet another example of a slice of the fantastic in popular culture that can be mined more deeply to provide us not only with entertainment in the externalization of our fears, but also an expression of something more, the concerns and questions about personal identity and the shape of the afterlife from the perspective of a particular religious tradition.

You are a very in depth thinker. I am currently suffering from post partum mush brain, so it’s dangerous for me to try and comment intelligently. However, if you are correct that the “born again” reference is a subtle critique of the Christian right at the time, I think it is a critique based on misunderstanding–common misunderstanding of what heaven will be like. I don’t know what it will be like of course, but I can guess it won’t be dull and boring…exiting stuff will go on. I hate that some people turn away from the Christian message because they think “our heaven” sounds boring, but…it happens…

Identity is difficult anyway. Who am I? Past history shapes who we are; I am not the same person as I was (say) 20 years ago, and yet there is a continuity of identity.

One of the best images I have come across for this is the one of the waterfall. The waterfall is always changing; the water being replenished with other water; it is never the same any instant, and yet the pattern of the waterfall remains a constant (let’s not go into long term erosion). So you have something changing all the time, but with a pattern that is constant – and different from other waterfalls.

David Kibner: “You will be born again into an untroubled world, free of anxiety, fear, hate…

Matthew Bennell: “David, you’re killing us!”

Jack Bellicec: “That’s not true. David’s right. Your minds and memories will be totally absorbed. Everything remains intact.”

Of course, in the book, Bennell asks the key question: if there is no difference, why the change? And Kibner tells him the duplication isn’t perfect, it’s like the unstable elements which scientists use – which is why the emotions are lost, and why everything is not intact after all – telling Bennell that is simply a means of making him go along with the change; and it is in fact a lie.

The book certainly plays with an American SF motif very strong for the period “the alien among us”, which certainly has overlay of “reds under the bed”, the idea of the alien who is a facsimile of a human being, but very different (and bad) motivations.

Interestingly English SF does not generally have the “alien among us” nearly as strongly (and English society did not have the same concerns with communism).

Tony, thanks for sharing a UK perspective on this.