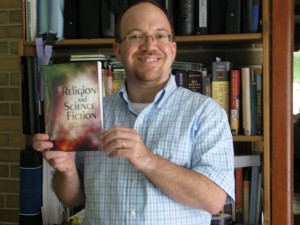

James McGrath has been a guest previously with an interview on religion and science fiction. He now returns to discuss the topic as the editor and contributor of a new book titled, appropriately enough, Religion and Science Fiction (Wipf & Stock, 2011). Following is the volume’s description:

James McGrath has been a guest previously with an interview on religion and science fiction. He now returns to discuss the topic as the editor and contributor of a new book titled, appropriately enough, Religion and Science Fiction (Wipf & Stock, 2011). Following is the volume’s description:

Religious themes, concepts, imagery, and terminology have featured prominently in much recent science fiction. In the book you hold in your hands, scholars working in a range of disciplines (such as theology, literature, history, music, and anthropology) offer their perspectives on a variety of points at which religion and science fiction intersect. From Frankenstein, by way of Christian apocalyptic, to Star Wars, Star Trek, Battlestar Galactica, and much more, and from the United States to China and back again, the authors who contribute to this volume serve as guides in the exploration of religion and science fiction as a multifaceted, multidisciplinary, and multicultural phenomenon.

TheoFantastique: James, thanks for helping me secure a review copy of the book, and for making time to participate in this interview. How did you personally come to an interest in the intersection between religion and science fiction as a fan and as a scholar?

James McGrath: Thanks for the opportunity to talk about the book with you! My interest began with science fiction fandom, and only later became a scholarly interest. I have been a science fiction fan for longer than I can remember – best illustrated, perhaps, by sharing one very vague memory from one Christmas very early in my childhood when I remember receiving a Star Trek play set and action figures. I remember watching shows like Star Trek and Battlestar Galactica as early as I have any childhood memories at all.

My main scholarly field is in fact New Testament. But because my position at Butler involves teaching more broadly in religion, and our program is small and flexible enough to allow for teaching in side interests, I have been able to teach on the subject of religion and sci-fi a couple of times. And as I discovered that the intersection of religion and science fiction was a subject that I could not only research, write about and teach on, but talk about with friends who were scholars working in very different fields from my own, the idea of collecting these diverse perspectives into a book was born.

TheoFantastique: From time to time I read online about whether science fiction is compatible with religion, and in one instance about whether there is too much religion in some science fiction television shows. When I read these things I wonder what the debate is about. I am thinking here of statements like those by David Hartwell who wrote:

A sense of wonder, awe at the vastness of space and time, is at the root of the excitement of science fiction…

To say that science fiction is in essence a religious literature is an overstatement, but one that contains truth. SF is a uniquely modern incarnation of an ancient tradition: the tale of wonder. Tales of miracles, tales of great powers and consequences beyond the experience of people in your neighborhood, tales of the gods who inhabit other worlds and sometimes descend to visit ours, tales of humans traveling to the abode of the gods, tales of the uncanny: all exist now as science fiction.

Science fiction’s appeal lies in its combination of the rational, the believable, with the miraculous. It is an appeal to the sense of wonder.

And I also think of other instances where science fiction may function for some in certain contexts as a sacred mythology. What is your perspective on this? Is this a case of secular ideology not recognizing sacred aspects to science fiction, or at least an overlap to religion in some instances?

James McGrath: I do think there is an overlap, and while it may be an overstatement to say that “science fiction is in essence” and by definition “a religious literature,” clearly some science fiction inherently is religious in character, and some science fiction blends seamlessly into religious expressions – not only in the form of UFO cults or Scientology, but in many other ways as well.

James McGrath: I do think there is an overlap, and while it may be an overstatement to say that “science fiction is in essence” and by definition “a religious literature,” clearly some science fiction inherently is religious in character, and some science fiction blends seamlessly into religious expressions – not only in the form of UFO cults or Scientology, but in many other ways as well.

While Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is regarded as the first work of science fiction proper, the reason we do not trace sci-fi back further is because as we go back into the pre-Enlightenment era, we cease to have something that we can call “science” in the sense in which we use that term today. But apart from the element of science that gives science fiction half of its name, many of the same sorts of stories have been told long before, in a continuous tradition that does not experience a radical discontinuity when sci-fi appears on the scene. Those earlier stories which involve beings from our world ascending to the heavens, or from the heavens to earth, have them doing so in the framework of a religious cosmology and by supernatural rather than scientific means. There’s definitely some continuity there, and sometimes it is in the details and not only the broad strokes.

And so there is something quite natural about science fiction being the means by which some religious questions – whether about the nature of reality, moral dilemmas, or our place in the universe – are asked and answered in the context of our present age.

TheoFantastique: Let’s move from these background questions to some specifics about the book you edited. With the previous examinations of religion and science fiction from various disciplinary perspectives, what does Religion and Science Fiction try to provide in filling the gap left perhaps by other treatments?

James McGrath: There have been numerous treatments of some particular aspect of the intersection of religion (broadly construed) and science fiction. The “X and Philosophy” series tends to include some treatment of religion, but is not exclusively about that. Treatments of Star Wars or The Matrix and religion have been offered, both from an academic perspective and as works using the films to advance and illustrate popular theology in this or that tradition. Treatments which seek to do justice to the broad sweep of religion, and the broad spectrum of sci-fi, have been relatively rare, at least until very recently. This isn’t surprising, since being comprehensive is difficult if not impossible. Leigh Grossman’s recently-published textbook seeking to cover a century of science fiction is massive in its physical width and height, printed in a very small font, and nearly a thousand pages long. One has no choice but to be selective in tackling science fiction, but in general treatments of religion and sci-fi have been narrower than the volume I put together, and so I wanted to offer something broader and that transcended the typical disciplinary boundaries reflected in and reinforced by previous books on the subject.

James McGrath: There have been numerous treatments of some particular aspect of the intersection of religion (broadly construed) and science fiction. The “X and Philosophy” series tends to include some treatment of religion, but is not exclusively about that. Treatments of Star Wars or The Matrix and religion have been offered, both from an academic perspective and as works using the films to advance and illustrate popular theology in this or that tradition. Treatments which seek to do justice to the broad sweep of religion, and the broad spectrum of sci-fi, have been relatively rare, at least until very recently. This isn’t surprising, since being comprehensive is difficult if not impossible. Leigh Grossman’s recently-published textbook seeking to cover a century of science fiction is massive in its physical width and height, printed in a very small font, and nearly a thousand pages long. One has no choice but to be selective in tackling science fiction, but in general treatments of religion and sci-fi have been narrower than the volume I put together, and so I wanted to offer something broader and that transcended the typical disciplinary boundaries reflected in and reinforced by previous books on the subject.

It was above all else that desire to bring the various disciplinary perspectives that have touched on the intersection of religion and sci-fi into a single volume, in which they themselves have the opportunity to meet and intersect, that led to the idea for the book Religion and Science Fiction. The norm is still for work in film studies, English and literature, religious studies, theology, philosophy, history and so on to look at the intersection of religion and science fiction largely independently of one another, each doing their own thing. I’m hoping this book will draw some of the bigger and wider scholarly picture to the attention of those interested in the subject from the perspective of the various disciplines represented among the book’s authors.

TheoFantastique: In Joyce Janca-Aji’s chapter on postmodern theology, one of the film’s she interacts with is Alien Resurrection. I must admit this is not one of my favorite films of the Alien franchise, but I was pleased to see some of her analysis of the film which brought out elements I hadn’t seen before. Some of these include “gender-conscious” elements that allude to Christianity. Can you touch on some of this and how this might function as a response to the patriarchal elements of “Christian science fiction” like Left Behind?

James McGrath: I learned a lot from the contributors to the volume, and Joyce’s chapter is a particularly good example. As a scholar of French language and literature with a secondary expertise in religion, and in particular Buddhism, Joyce placed the Alien films – and Left Behind – into conversation with other films that I might never have encountered had her chapter not introduced me to them.

James McGrath: I learned a lot from the contributors to the volume, and Joyce’s chapter is a particularly good example. As a scholar of French language and literature with a secondary expertise in religion, and in particular Buddhism, Joyce placed the Alien films – and Left Behind – into conversation with other films that I might never have encountered had her chapter not introduced me to them.

The Left Behind series is typified, inasmuch as I am familiar with it, by male characters whose allegiance may change over the course of the story, but is either on one side of the line or the other, either with Christ or Antichrist, reflecting the black-and-white worldview of Christian fundamentalism and its premillennial dispensationalist eschatology. The Alien films, on the other hand, not only feature a female lead and other strong female characters, but focus on reproduction, motherhood, and the possibility of boundaries being transgressed, as happens whenever one human life begins within the confines of the body of another, the mother. Not only the divide between good vs. evil, but also that between human vs. alien, is compromised in the Alien films, in a way that gets at the complexities of human personhood and the ambiguities of moral allegiances which are treated less well by the cardboard stereotypes of Christian apocalyptic sci-fi – the villains of which rarely seem to have plausible motivations for their actions or personalities that are more than caricatures.

TheoFantastique: C. K. Robertson has a chapter with a subtitle that refers to “Old Mythologies in New Guises.” In this analysis Robertson refers to these comic characters and gods as “new household gods,” and that this “visible religion” might have great appeal for today’s comic fans as those on the margins, much as the ancient pantheon appealed to the marginalized giving Christianity with its invisible god a run for its money. Leaving the first century context aside, I wonder whether this might not be so much the case today with the “geeks” leading in pop culture in so many ways, from films based on comics to the pop culture phenomenon of Comic-Con. What might your thoughts be on this?

James McGrath: There are forms of religion, such as in Reform Judaism or the non-realist theology of Don Cupitt, which focus on language about God as a symbolic expression of our highest values. There is no particular reason why figures from ancient pantheons, or from comic books, could not serve a similar function. In fact, science fiction fandom is famous for having inspired people to shape their lives in relation to its stories. And while those who have listed “Jedi” as their religion on recent censuses are probably no stronger with the Force than Han Solo, and did not intend this affiliation to be taken particularly seriously, it remains the case that many people relate to sci-fi stories more than to traditional religious ones, and whether they acknowledge it or not, look to those stories for some of the same purposes that religious believers look to their own stories.

James McGrath: There are forms of religion, such as in Reform Judaism or the non-realist theology of Don Cupitt, which focus on language about God as a symbolic expression of our highest values. There is no particular reason why figures from ancient pantheons, or from comic books, could not serve a similar function. In fact, science fiction fandom is famous for having inspired people to shape their lives in relation to its stories. And while those who have listed “Jedi” as their religion on recent censuses are probably no stronger with the Force than Han Solo, and did not intend this affiliation to be taken particularly seriously, it remains the case that many people relate to sci-fi stories more than to traditional religious ones, and whether they acknowledge it or not, look to those stories for some of the same purposes that religious believers look to their own stories.

TheoFantastique: I found it interesting that Robertson also refers to the mythic superhero tradition, and while it is acknowledged that this “tradition is not religious,” Robertson acknowledges that “the comics subculture treasure it with near-religious devotion.” In light shift of religion beyond the more traditional boundaries of conventional religions, and the interesting social space between the secular and religion, is it possible that various science fiction mythologies might be understood to function as sacred mythologies for some?

James McGrath: Absolutely. I assume that you are asking about ways in which this might go beyond the sorts of phenomena already mentioned in my answer to the previous question. In Dynamics of Faith, Paul Tillich talks about those myths which are recognized as mythological and symbolic in character as “broken myths.” He suggested moreover that the recognition of myth as myth, the breaking of the myth, is crucial to the avoidance of idolatrous faith. If Christianity can find expression as a religion in which the mythical character of some of its stories and Scriptures are recognized, and yet nevertheless still appreciated and harnessed as the means to expressing ultimate concern, then why could already broken myths (such as those in comic books or in science fiction TV and film) not be utilized for a similar purpose?

As for what that might look like if fully explored and utilized, it is hard to say. But I see no reason why it could not be done.

TheoFantastique: You served not only as editor of this volume, but also as a contributor with a chapter on artificial intelligence and religion. How can science fiction help us, including theologians, reflect on important issues related to robotics and AI?

James McGrath: Science fiction is particularly good at creating situations that could not arise in the present with our current technology, but which allow us to explore important philosophical or moral questions. This is true not only of instances when already-existing sci-fi shows like Star Trek: The Next Generation use a transporter accident or the trial of an android to explore questions of identity and human nature, but also when philosophers write what are essentially sci-fi stories to illustrate their points, as happens for instance with Daniel Dennett’s classic piece “Where Am I?”

James McGrath: Science fiction is particularly good at creating situations that could not arise in the present with our current technology, but which allow us to explore important philosophical or moral questions. This is true not only of instances when already-existing sci-fi shows like Star Trek: The Next Generation use a transporter accident or the trial of an android to explore questions of identity and human nature, but also when philosophers write what are essentially sci-fi stories to illustrate their points, as happens for instance with Daniel Dennett’s classic piece “Where Am I?”

In the case of robotics and artificial intelligence, the exploration of such possible future technology is useful as a way of preparing for a time when such tech may become reality. But more than that, it allows us to explore questions that are relevant now with respect to our own humanity and our notions of personhood. It is precisely because there are questions about human personhood and consciousness that it seems impossible to answer through objective analysis, but only through empathy and analogy with our own subjective experience, that it becomes clear that if we are to press ahead with the effort to create full-fledged artificial minds and persons, then we must be prepared to address the moral issues which are raised. And since we will almost certainly not be able to say definitively “This is a real artificial person” or “This is merely a machine imitating personhood,” it will (as I suggest in my chapter) be a test of our humanity when we decide whether to err on the side of giving rights to our creations, or keeping them as slaves. And the very act of reflecting on the question, even when the technology does not currently exist, gives us the opportunity to reflect on our own beliefs and values.

TheoFantastique: What have the responses been thus far to the book, and are there any plans at this point for a follow up volume?

James McGrath: The responses have been positive, and interest in the subject matter seems to be continuing to grow. There will be a session at the American Academy of Religion conference this year on religion and science fiction, and I am looking forward to participating in it. My impression is that both in the academy and more generally, the novelty of looking at religion and science fiction is wearing off, and so it will be interesting to see whether the subject proves to be of lasting interest rather than a passing fad. But since the connection between religion and sci-fi has deep roots, I expect the interest in the topic that we see at present to continue or increase in the future.

I don’t have plans for a follow-up volume at this point, but if I do pursue that at some point in the future, it might perhaps take the form of a single-author work of my own, seeking to bring together some of my thoughts on a range of topics, literary works, shows, and films, or perhaps (if what I have just described proves too enormous) simply doing what others have already done, taking one particular series and focusing my attention there. Doctor Who and time travel were under-represented in Religion and Science Fiction, and so perhaps I could make amends at some point in the future by focusing on that topic or show. I also have an idea for a science fiction short story that would explore religious themes, and so perhaps I will find the time to turn that idea into a published work at some point in the not too distant future.

TheoFantastique: James, thank you again for your time, and thoughts on Religion and Science Fiction.

I enjoyed the interview. I love science fiction and I believe that science fiction and religion can co exist. I believe that if there are aliens out there, then God created them. I am the author of, Tale Spinner a science fiction novel published by Otherworld Publications. It is available on Kindle at Amazon. My blog site is http://dhdonaghe.blogspot.com/