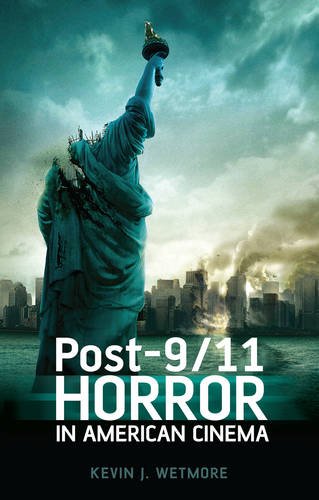

Kevin Wetmore returns to TheoFantastique to discuss his new book Post-9/11 Horror in American Cinema (Continuum, 2012). Wetmore is an associate professor of theatre at Loyola Marymount University, the author and/or editor of ten books including The Empire Triumphant: Race, Religion and Rebellion in the Star Wars Films, and a contributor to numerous volumes on sci-fi, pop culture and religion, including essays on Godzilla, Star Wars, and Battlestar Galactica. Previously he was a guest here when he discussed his book Back from the Dead, which looked at how zombie films reflect the culture of their time.

TheoFantastique: Kevin, your book looking at how 9/11 impacted American horror films was an enjoyable read. When did you first begin to notice that post-9/11 horror was surfacing as an influence, and what specific types of things do you see that is new or amplified that differentiates it from pre-9/11 horror?

Kevin Wetmore: I began to notice that more and more films were concluding with the deaths of the entire cast and that the rules of conventional horror were being violated all over the place. I also noticed a much more dark and bleak attitude within these films. Lastly, like many I noticed the large number of found-footage films. While there are economic reasons to do found footage films (they are cheaper to make, don’t need stars, and can go for easy scares), I think the experience of 9/11, mediated as it was for most of the world, and of the events since, also experienced by most through images on a television screen rather than direct experience, has made people come to perceive found footage films in the same way they do disasters and terrorist attacks. There is a lot of Hurricane Katrina in Paranormal Activity; there is a lot of 9/11 in [Rec] and Quarantine. So sometime around 2008 I began writing about what I saw were the changes in horror as a result of 9/11.

It’s not that 9/11 introduced anything new into horror, but what it did was amplify certain elements and disempower others. We also began to recapitulate 9/11 in film form, so you get movies like Spielberg’s War of the Worlds, Cloverfield, Vanishing on 7th Street, Mulberry Street and Pulse, all of which recreate 9/11 as a horror film, all of which directly quote images from that day.

Other ways that 9/11 has changed horror is an increase in body counts, a transformation in morality in horror films, and an increased nihilism and bleakness. So in the remake of Dawn of the Dead, by the end of the credits all of the characters are dead. Whereas pre-9/11 slasher films dealt with a rather conservative morality – do drugs, have premarital sex or behave foolishly in the woods and you die – post-9/11 horror shows that you die not because of what you did but because you were in the wrong place at the wrong time. And in The Strangers, when asked why they were torturing the couple, one of the killers simply responds, “Because you were home.” The monsters get you because of where you were standing, reflecting the reality of 9/11 itself: if you were on one floor of the twin towers, you lived, one floor up and you died; took one flight on 9/11, you flew into a building, another leaving ten minutes later and you lived. Death is random, meaningless, and undeserved. Horror after 9/11 reflects a much scarier world without rules.

TheoFantastique: One of your discussions that I found interesting was the fear of religion. In a post-9/11 environment a fear of terrorism related to Islam is understandable, but with this has also come a fear of Christian fundamentalism. Can you share how this has surfaced in post-9/11 horror films and why it surfaces along with fear rooted in Islamic extremism?

Kevin Wetmore: In the book I argue that religion in horror film is rooted in several different fears. First is the idea that the tenets of religion are real, which means that evil as a personality, as a force, as a group of entities is real. The devil exists. Demons exist. Evil ghosts, monsters and long-legged beasties exist. That is a scary idea and goes against pre-9/11 horror. Look at the most popular horror films of the 1990s – Scream, I Know What You Did Last Summer, Silence of the Lambs – they are all about human monsters, human killers. But the past decade has brought us more films about exorcisms than the wake of the original Exorcist, more movies about demons and ghosts. Again this is not to say that human monsters are passé – for God’s sake there are seven Saw films – but 9/11 brings demons, devils and monsters back to the fore.

Second is the fear of fundamentalism. Yes, Islamic fundamentalism was behind 9/11, but to the best of my knowledge there has only been one film that deals with horror from Afghanistan or Iraq and that is Red Sands. Instead, we prefer the devil we know, if you’ll pardon the pun. I think there is also a concern about our own growing fundamentalist streak in this nation. In the wake of 9/11, President Bush used a lot of religious and especially apocalyptic language. Evangelical Christians cast the war or terror as a holy war. nd we have had our own instances of Christian fundamentalists doing things in this nation that could be perceived as terrorism – shooting of doctors who perform abortions; the Westboro Baptist Church protesting military funerals with hateful, homophobic rhetoric; just recently one minister proposed putting homosexuals into concentration camps and “letting them die out” and his congregation approved. Hollywood has always had a problematic relationship with religion, but after 9/11, fear of fundamentalism trumps fear of Islam. With fundamentalists, it does not matter if the devil is real or not, because they are happy to kill and torture in God’s name.

Third, linking the two, is the religious bait and switch – the religious person who is somehow involved in devil worship, or at least facilitating the work of the devil, like in House of the Devil, The Last Exorcism, The Rite, The Reaping and Devil Inside. We distrust people who live their faith a bit too openly. Partly this is because of fallen idols in our own culture: the Catholic Church’s pedophilia scandal, the fall of Ted Haggard, the too-numerous-to-count instances of pastors being caught in sexual scandals combined with the anti-progressive stance of many denominations (the active work of the Catholic Church and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in California to outlaw gay marriage, for example) reinforce the idea that behind closed doors religious people are even more evil and dangerous than those they speak out against. So we get films in which the rural Methodists are actually Satanists. And they want to sacrifice you to their dark master.

TheoFantastique: One of the most interesting post-9/11 horror films for me is Spielberg’s The War of the Worlds. You mention how this film is very much a representation of the experience of 9/11. It is curious for me in that Spielberg has had a more positive view of aliens in past films (as well as in his personal philosophy of extraterrestrials), and yet it is so dark and depicts the experience of 9/11 and the refugees from war as well. Strangely, one of the first major buildings destroyed in the film is a church, and yet the ending of the film includes the same narration of divine planning which has saved humanity much as in the 1953 version of the film (both representing substantial changes from Wells’ story). In your view, what was Spielberg doing in this film which so graphically depicts not only war (a focus of the director in the past), but also 9/11 and the religious imagery in the film?

Kevin Wetmore: War of the Worlds may end up being Spielberg’s most criticized film, mostly because if its direct quoting of 9/11. More than one critic referred to it as “pornographic” and “needlessly exploitive.” I think in some ways Spielberg was attempting to rewrite 9/11 in a sense. You mention his war and alien fixation, but Spielberg also is a director driven by the need for redemption and reintegration. Heroes must win in Spielberg’s world. His two Second World War movies are Schindler’s List, in which even the horror of the Holocaust is somehow mitigated by Schindler’s work and the personification of Nazi evil in the form of Goeth is justly punished at the end of the film, and Saving Private Ryan, in which even with the deaths of most of the focal characters, Private Ryan is saved and returns to the graves of the men who saved him in order to thank them and show his family who the heroes of the war were. Spielberg wants human action to mean something. After 9/11, much pop culture went nihilistic and existential – bad things happen because bad things happen and we cannot stop it nor even always fight against it. Spielberg on the other hand shows New York and New Jersey being devastated, but a single father is able to get his children safely to Boston and the aliens are defeated. It’s 9/11 with a happy ending, which is why critics object to it.

For me, the defining image of the film is the moment when Tom Cruise and his children hide in the basement of an abandoned upper-middle class house, clearly far larger and nicer than the one Cruise’s character owns. They hear something crashing into the house above and the implication is that the aliens are attacking. Come morning, however, Cruise exits the basement and discovers that a passenger jet liner has crashed into the house (somehow without setting it on fire!?!). It is the literalization of a metaphor: 9/11 is when a plane crashed into every living room in America and changed the world forever. That, I think, is the most effective visual element of War of the Worlds, not the more direct quoting of boards full of photos of the missing, the running crowds or the destruction of buildings seemingly lifted directly from footage of that day.

I suspect religion is not as important in the film. Yes, a church is destroyed first, but other than that there is little religious iconography or theological thought in the film. If anything, it depicts people with no faith trying to survive in a world that suddenly makes no sense and is far more dangerous than any of them thought.

TheoFantastique: How did 9/11 contribute to the so-called “torture porn” subgenre as the nation wrestled with concerns over torture and “enhanced interrogation” in relation to terrorism?

Kevin Wetmore: 9/11 itself did not contribute to torture porn, but American activity afterwards literally invented the genre. In 2002 America began keeping prisoners of war in a camp in Guantanamo, followed by the atrocities at Abu Ghraib in 2003. There were iconic images of people chained in jumpsuits, men made to strip naked and get into human pyramids or be attacked by dogs. Most famous was the hooded man, standing on a box, his face hidden, electrodes attached to his body. These images could have been from horror films or from archives on the Nazis. Instead, these were Americans doing it. Shortly afterwards we began to learn about “enhanced interrogation” and water boarding. There was a huge national debate about torture, which was a deep concern because we were doing the torturing, or at least were the ones sending these people to places we knew they would be tortured. As a result two trends began in horror. The first was the exploration of torture defining Americans abroad. The first two Hostel films show people being tortured not because of anything they did but precisely because they were American. The second one shows Americans paying to torture Americans. The Saw series very rapidly came to be about how the human body might be tortured. So we were exploring our role as torturer while distancing the experience by saying, “Hey, Americans get tortured for being American. It’s a far scarier world for us.” Rapidly, films like Turistas, The Last Resort and even The Ruins follow in which young Americans are tortured and killed because they are young Americans abroad. In almost every single one of these films, however, there is a reversal. One of the people escapes and then begins hunting, torturing, and killing the torturers. The torture of the people who pay to torture Americans and those who work for Elite Hunting in the Hostel films is justified because they started it. In other words, America does not torture people; we are driven to do so when they do it first and we have no other choice. Torture porn allows us the fantasy of torturing without being guilty of being a torturer.

TheoFantastique: I was pleased to see your discussion of The Mist, one of the best horror films of the first decade of the new millennium, in my view. How did this film draw upon 9/11 to include a strong sense of nihilism, despair, and fear of institutions including the military and religious fundamentalism?

Kevin Wetmore: I loved Stephen King’s novella. I also thought the last lines were wonderful, the idea that this small group had driven south from a Maine still covered in the mist and the two words keeping David going being “hope” and “Hartford” (it also helped that I grew up in Connecticut). The film, however, just blew me away with its unrelenting bleak nihilism and despair. Ironically, the film version, in which the mist dispels fairly quickly, is far more devastating than the implication that the entire world might be covered with the mist and things have changed forever found in the story. The film version keeps most of the novella intact, creating a microcosm within the supermarket. We have a group of people who, faced with an attack from outside, devolve into separate camps: those who do not believe there is a threat, those who want to fortify and then respond as coolly an rationally as possible, and those who see a larger metanarrative in the events (“prophecy is coming true”) and wish to respond through fear and violence. Nobody escapes. Mrs. Carmody is the voice of a judgmental fundamentalism that wants to divide the supermarket into the sheep and the goats, and then sacrifice the goats. Brent Norton thinks the townies are having fun with him and does not believe there is a genuine threat. The military initially keeps information from the civilians, but when soldiers commit suicide, folks begin to realize that the situation is far worse than they imagined. David just wants to get his son back home and rescue his wife. People respond to every crises and every response proves to be unhelpful at best and devastating at worst. Finally, a small group of rational individuals are able to get out to the car and escape, only to learn David’s wife is dead. When they run out of gas, David kills everyone in the car, including his son, to spare them the pain of the monsters in the mist, only to learn seconds later that they were about to be rescued by the Army. Adding insult to injury, the woman who left the supermarket alone after no one would go with her successfully rescued her children and is safe with the military. David just falls to his knees and screams. It’s beautiful. It’s brilliant. And it is one of the most painful moments on film in the last decade. In the theatre where I saw it, the audience, which had been screaming and laughing and responding to the film as one does to horror films, fell silent at that moment. No one talked on the way out except in hushed whispers. It was like we had just seen an atrocity. That, to me, was the heart of the horror of The Mist – no matter what you do, it’s the wrong thing, and those you love will die as a result, but they did not need to. The Mist shows us a world without meaning, without hope, with only bleak despair. The War of the Worlds reproduces 9/11 to make it safer for us; The Mist reproduces 9/11 as it was, not playing at horror but showing loss without hope.

TheoFantastique: At one point in your book you state that “a major theme of horror films of the last decade is that exorcism does not work.” Given the popularity of The Exorcist in past decades, and to expand a little on our discussion of the fear of Christian fundamentalism previously, what types of shifts have taken place that results in a different perception of the place of Satan, diabolical spirits, and exorcism so that these things no longer offer hope?

Kevin Wetmore: It’s funny but yesterday (Friday the 13th) I went to see The Exorcist on stage, where an adaptation of the novel is playing right now in Los Angeles, and I also just showed the film to a class, many of whom had not seen it before. One of the main things folks have said about both is that the story is still scary, but now somehow dated. What people forget, though, is that the exorcism in that film is ultimately a failure. Prayer and rituals do not drive the demon from the girl. Rather, Father Karras demands that the demon “come into me,” and then commits suicide so as to free her from possession. So even the original film does not have much faith, pardon the pun, in ritual and prayer, even if it does have faith in faith. However, look at the post-9/11 prevalence of movies about possession and exorcism: The Exorcism of Emily Rose, The Last Exorcism, The Rite, The Devil Inside, Dominion, and Exorcist: The Beginning, to name just the best known ones. So, as I said before, evil is real. The devil is real. Demons are real. And our biggest weapon against them is a rite that often does not work. The exorcisms do not work in The Last Exorcism, The Exorcism of Emily Rose and The Devil Inside. As often as not, the possessed person dies. More often than not, others die too. As part of the larger continuum of post-9/11 horror, exorcism films show that we have little hope in the face of evil out to get us. Satan, as it turns out, is a diabolical Osama bin Laden. He is out to get us and it will be a long time before we can track him down and defeat him.

TheoFantastique: You include a discussion of The Village, in my view an underrated film by critics of Shyamalan. How did this film’s use of fear through the creation of monsters as a means of social control connect to America’s experience of fear post-9/11?

Kevin Wetmore: The thrust of that film is manufactured fear. You find this also with Cry Wolf, which pretends to be a run-of-the-mill slasher film but turns out to be an elaborate plot to generate chaos for nefarious purposes, one subgenre of post-9/11 horror is the “manufactured fear movie” – films in which the monster or threat has been entirely invented by an individual or a group in order to achieve something else. The elders of the village have created “the ones of whom we don’t speak” as a means of social control. No children or young adults wander too far because of fear. They are also able to preserve the status quo and power structure – only the elders know how to fight the monsters that live in the woods. The problem occurs when Noah finds a costume and begins doing what the monsters in the woods do, which is frighten people and kill things. You must be careful of the monsters you create because they tend to come to life. Likewise, in Cry Wolf, a group of students create “The Wolf”, a serial killer supposedly on their campus. It is revealed, however, that the whole creation of this hoax was so that on girl could get revenge on a teacher who broke off their affair. These films and others like them echo the government’s use of fear after 9/11. We had a color-coded chart for how scared we should be. We also used al-Qaeda as a boogey man to do what we wanted, from the invasion of Iraq to encouraging people to vote a particular way (I am thinking here of Dick Cheney going on the Sunday news shows and saying a vote for John Kerry increased the likelihood of terror attacks). We now take away nail clippers on airplanes because of “the ones of whom we don’t speak,” but insist that we be free to buy armor-piercing rounds for semi-assault weapons. Since horror is the genre in which we explore fear, it is logical that it also be the genre in which we explore the exploitation of fear.

TheoFantastique: Thank you again for your thoughts, and for the great book.

Kevin Wetmore: Thank you for the opportunity and your kind words.

Related posts:

“Wetmore on Romero Zombies as Markers of Their Times”

“Kevin Wetmore on Dawn of the Dead (2004) and the Zombie Terrorist”

There are no responses yet