A piece in this weekend’s Los Angeles Times website holds dire implications for classic fantastic films. It is titled “Perspective: Millennials seem to have little use for old movies” by Neal Gabler. The point of departure for Gabler’s essay is the release of the new Spider-Man film, just a decade after the release of the film that started the franchise. According to those quoted in the article, such a period of time is an eternity for millennials, a major viewing demographic. Beyond this, it also demonstrates something significant about young people and their relationship to film. Gabler writes,

Young people, so-called millennials, don’t seem to think of movies as art the way so many boomers did. They think of them as fashion, and like fashion, movies have to be new and cool to warrant attention. Living in a world of the here-and-now, obsessed with whatever is current, kids seem no more interested in seeing their parents’ movies than they are in wearing their parents’ clothes.

This is very different than my experience, and perhaps the generation in which I was raised. I remember watching films as a kid with my dad, and even without him when my local Fox station held its annual summer film festival which played titles like King Kong, Dracula, The Caine Mutiny, and The Maltese Falcon. As a result I was familiar with stars and films from my parents and even my grandparents generations, a phenomenon which continued as I built upon this with the addition of successive aspects of cinema history. From time to time in the past my now grown children would find me watching black and white films, whether horror films from the 1930s and 1940s, or science fiction-horror from the 1950s, only to ask what obscure films these were, and demonstrating not only no awareness of such things, but no interest as well. In their thinking, surely only current films were worth watching and appreciating. With this in mind it would seem that Gabler’s perspective may be correct, and that millennials do indeed view film not so much as art or history valued in its past expressions as much as in the present, but rather as a trend as fleeting as today’s fashion.

But perhaps such attitudes to film may not be as widespread as Gabler fears. He notes that scientific studies on such questions have yet to be undertaken:

There are, unfortunately, no studies of which I am aware that examine the relationship of millennials to old movies. At best we have dated surveys about the antipathy of young people to black-and-white films. But MTV did conduct a study recently of how young people relate to contemporary films, which found that movies are deeply embedded in the social networking process. Young people begin tweeting about films in anticipation of their release and continue discussing them after the release so that the buzz is now more sustained than it has been. In effect, movies, new movies at least, create an occasion for an ongoing conversation.

But the fodder for conversations on Facebook or Twitter are hardly the stuff of depth in cinematic appreciation, and Gabler’s comments earlier in the essay on millennials and their stance on “old movies” should raise concerns. He writes,

They find old movies hopelessly passé — technically primitive, politically incorrect, narratively dull, slowly paced. In short, old-fashioned. Even Tobey Maguire’s Spider-Man is a Model T next to Andrew Garfield’s rocket ship of a movie. And Model Ts get thrown on the junk heap.

This also raises the question about how millennials define “old movies.” From someone my age this might be understood as films in the 1920s or 1930s, but from a millennial perspective it would appear that any film with a shelf life beyond ten years is in danger of begin cast aside for the latest cinematic fashion update.

I would also suggest that Gabler’s essay poses dire implications for the future of classic fantastic films of the silent era and on into the Universal films of the 1930s and 1940s, and beyond that the horror-science fiction films of the 1950s (and possibly even later films in following decades depending upon how older films are defined). These films, and others, have been extremely influential on a previous generation of filmmakers, and much of contemporary horror, science fiction, and fantasy, has come about as a result of the influence of this body of material. What forces will influence the preservation of these films, not only as entertainment, but also as art, and the foundation of a variety of subcultures? Presently their continued financial value is a sustaining force, as studios release new versions of these films on Blu-ray for contemporary audiences. The forthcoming release of Universal Classic Monsters: The Essential Collection is a welcome example of this. They will also survive in terms of homage, and a contemporary example of this is reflect forthcoming comedy-horror animated films, including Hotel Transylvania and Frankenweenie. But beyond this, if millennials and their attitudes toward “old movies” represent one of the primary forces that shape how film is not only produced for the future, but also how it is remembered and taken care of from the past, then it may be that a vast array of horror, science fiction, and fantasy films are in danger of loss in the following decades. Gabler recognizes this potential for older films in general. He concludes his essay with these sober words:

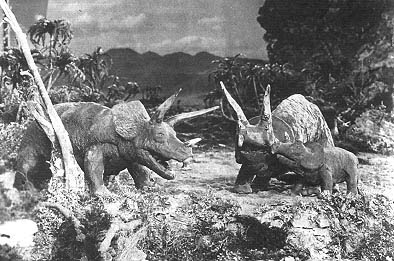

All of this makes it tough not only for old movies to survive but for movie history to matter. There is a sense that if you can’t tweet about it or post a comment about it on your Facebook wall, it has no value. Once, not so long ago, old and new movies, middle-aged audiences and young audiences, happily coexisted. Movies brought us together. Now a chasm widens between the new and the old, one aesthetic and another, one generation and another. It widens until the past recedes into nothingness, leaving us with an endless stream of the very latest with no regard for what came before. Old movies are now like dinosaurs, and like dinosaurs, they are threatened with extinction.

I have raised this concern previously and wondered what might be done as a result. How might fans and the organizations and networks they have created work together with film and popular culture historians and scholars to preserve older fantastic films? And how might older generations of fans work with those in younger generations to educate and inspire them about their value? Perhaps we can find ways to build bridges across the chasm, and in so doing save our beloved cinematic dinosaurs from extinction.

John, I’ve seen this phenomenon all-too often. I attribute it to the fact that this is the first generation to have its own media spoon-fed to it. When we were kids, there were no 24-hour channels devoted to kids’ programming. We had to watch what the grown-ups were watching. There was a handful of channels, and we learned to appreciate all different kinds of things, simply because that’s what was on. Not so anymore. If a young person wants to expose himself only to what is new and tailored just to him, he can do so very easily. It is a simple matter to avoid older media one is less interested in, because it’s been ghetto-ized on home video and specialty cable channels. There is no longer ready opportunity to expand your horizons as easily and prevalently as there used to be. That said, I don’t know if it’s as widespread as we fear it is. There will always be young people who take an interest in entertainment before their time, even if it is a lower percentage now. For instance, my ten-year-old daughter, without any direct influence from me, recently took her mother to the video store and rented the 1945 horror anthology film Dead of Night. Of course, that’s because I’ve worked to raise her with an open mind about old film, TV, music, literature, etc. You have to work at it, but parents can and do make a difference.

This is the same thing people have been saying about young people for decades. They said it about my generation and they said it about my parents and my grandparents. And NOT every movie is a classic, no matter how old it might be.

For example, Mrs. MIniver was considered an amazing movie in its time because it was some kind of a WWII propaganda film to get America into the war. Greer Garson won the Academy Award for essentially looking pretty and delivering her lines without choking. The music was static and it dragged on. YEt, it was supposedly a “classic” and AMazon reviewers are still claiming that it’s a wonderful film.

But it’s not. It’s an old movie that sucks. When the generation that loved this movie dies, it will not be mourned. Just like no one is really going to care about AC/DC in 30 years.

I can sort of see both of the sides to this argument. I’m 30 and grew up watching Universal,Hammer and TV form way before i was born. My daughter’s 8 and loves Tom Baker in Dr Who but would never sit through anything in b/w. Even i find it hard to sit through some films and programs now without ffwd through them. There’s a quasi-darwinian side to this if the script and plot remain revelant to some people then there will alway be a market for older films and tv on the internet but some films and tv programs will eventually disappear because we evolve as a culture. Film Four are still broadcasting films from 50/60 years ago but maybe in 50/60 years more some films and tv programs will become the preserve of fan clubs and media studies students