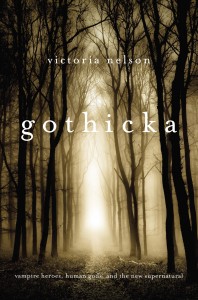

This is an exciting time for those interested in the intersection of religion, popular culture, and the fantastic genres. A number of scholars are producing fascinating works in this area, and one of those is Victoria Nelson. Victoria is an essayist and fiction writer who teaches in the Goddard College graduate program in creative writing. She is the author of The Secret Life of Puppets, and the new volume, Gothicka: vampire heroes, human gods, and the new supernatural (Harvard University Press, 2012). Victoria agreed to return to TheoFantastique. In the past she discussed the work of Guillermo del Toro, and now she responds to my voluminous questions on Gothicka.

This is an exciting time for those interested in the intersection of religion, popular culture, and the fantastic genres. A number of scholars are producing fascinating works in this area, and one of those is Victoria Nelson. Victoria is an essayist and fiction writer who teaches in the Goddard College graduate program in creative writing. She is the author of The Secret Life of Puppets, and the new volume, Gothicka: vampire heroes, human gods, and the new supernatural (Harvard University Press, 2012). Victoria agreed to return to TheoFantastique. In the past she discussed the work of Guillermo del Toro, and now she responds to my voluminous questions on Gothicka.

TheoFantastique: Victoria, thank you for an enjoyable read, and your patience with my questions. I’d like to explore some of your ideas in Gothicka. When you talk about the “sub-Zeitgeist” of dark supernaturalism in popular culture, what do you mean by this, and how does it relate to the Gothic of the past?

Victoria Nelson: “Sub-Zeitgeist” is a label I coined, a bit tongue in cheek, in The Secret Life of Puppets. It refers to the no-man’s-land of popular culture in all its lowbrow manifestations—genre film, mass market paperbacks, comic books — the fads, fancies, and stories the high culture of “serious” art and intellectual inquiry routinely excludes.

Through most of the 20th century, you rarely find the supernatural represented outside pop culture genres. Even there, it has mostly been cast in terms of the bad stuff — evil, terror, horror. The only exception was Victorian children’s fantasy, another Gothick subgenre that eventually morphed into the Harry Potter series and so much more.

That’s our unique cultural legacy from the Protestant Reformation, which planted the idea that anything uncanny was likely to be the Devil’s work, and also from the Scientific Revolution, which focused squarely on cause and effect within the material world. By the end of the 17th century, miracles and other divine/supernatural interventions in daily life were no longer considered possible in mainstream Euro-American culture.

The Gothic genre began in the mid-18th century as part of a sub-Zeitgeist reaction to this new rationalism. These lurid novels about violence, incest, fornicating nuns and priests, brooding castles and abbeys harboring dark secrets began pouring out of England as part of a wave of nostalgic medievalism and a love-hate relationship with the old Catholicism. One strand of the classic Gothic incorporated supernatural events, another didn’t, but as this very durable literary shock genre flourished and morphed over the next two hundred and fifty years into Victorian ghost stories, pulp horror fiction, 20th century B movies, and mainstream films and novels today. By the 21st century, significantly, the supernatural element it carried became greatly magnified and the Gothick stopped being all about the dark and scary side.

TheoFantastique: How do you see this incorporating elements of gnosis and premodern Catholicism?

Victoria Nelson: Gnosis is a huge category that covers a lot of territory. There’s the original Gnosticism of Western late antiquity, a religious-philosophical tradition that influenced and overlapped with early Christianity.

Victoria Nelson: Gnosis is a huge category that covers a lot of territory. There’s the original Gnosticism of Western late antiquity, a religious-philosophical tradition that influenced and overlapped with early Christianity.

Then there’s the gnosis we think of generically as an intuitive, nonrational, transcendental way of knowing. It contrasts with the rational-empirical, scientific, information-bearing episteme most Westerners valorize today as the only legitimate way of accessing knowledge. I did a whole long rap about these two in the puppet book.

For Renaissance thinkers like Giordano Bruno, gnosis was a process, a mystical act of knowing God in which the knower himself also becomes divine. This is the kind of gnosis I see all over the Gothick today, and in particular in the kind of spiritual practice called “personal gnosis,” where a person basically fills his or her Internet shopping cart full of mix-and-match eclectic beliefs drawn from Wicca, Buddhism, Egyptian mythology, and many other mythic strands to create a kind of personal religion. There’s a tendency to laugh at this practice, but I don’t. A lot of very thoughtful people do it. The only danger I see is a tendency to overtrust one’s own intuition at the expense of collective wisdom or higher principles that have been debated and refined by many minds over a long period of time.

As for premodern Catholicism, the kinds of personal gnosis practices we see growing out of Gothick fictions and films in the last thirty or so years show some odd similarities to the popular religion of medieval Catholic Europe — all that worship of the female god Mary, a host of strange and peculiar saints of both sexes, even a female or hermaphroditic Jesus. The medieval Christian gods, goddesses, and demigods are very much equivalent to the divinities, demigods and demigoddesses of other traditional religions like Hinduism. More significantly, these female and “monstrous” supernatural figures were mostly benign and beneficent. So are the main characters of today’s Gothick. Think Bella, Shrek, Hellboy. Characters like these form a kind of subliminal anti-pantheon to Protestant Christianity’s three male gods.

TheoFantastique: You refer to Gothick subgenres as involving “an implicit heterodox spirituality,” and further you state that we “are moving intuitively toward an image-based, animistic, supernaturalist orientation that has some common features with the worldview that fueled this older historical substratum of our culture.” Can you unpack some of the meaning of this for us, and provide a few examples of how this plays out in popular culture?

Victoria Nelson: Protestant Christianity is supremely a religion of the word. It’s text based and iconoclastic, anti-image, and it came, as all great religious movements do, at exactly the time it was most needed. It reformed a corrupt and backward-leaning institution, gave every person who could read and write access to scripture, and as an extra benefit paved the way for the mind-bendingly wonderful developments that science and technology have given us.

But history isn’t linear and progressive; it’s cyclical and repetitive. The very technology that grew out of the epochal separation of spirit and matter that took place between the Renaissance and the Enlightenment is leading us not backward but spiralwise into an intensely visual culture in which we navigate iconic imagery fueled by film, videogame, and the Internet. We tend to allegorize the Net into a “real” space, an unconscious habit that leaves us far more open to the possibility of dimensions that aren’t experienced by the five senses. An integral part of this new culture is the budding spirituality of personal gnosis I mentioned above that uses pop culture stories of fully realized alternative worlds to spin new mythologies and inspire new spiritual practices. I believe the influence of these new pop mythologies, as they saturate our imaginations, may paradoxically begin to foster a more sophisticated consideration of spirituality in mainstream secular culture.

But history isn’t linear and progressive; it’s cyclical and repetitive. The very technology that grew out of the epochal separation of spirit and matter that took place between the Renaissance and the Enlightenment is leading us not backward but spiralwise into an intensely visual culture in which we navigate iconic imagery fueled by film, videogame, and the Internet. We tend to allegorize the Net into a “real” space, an unconscious habit that leaves us far more open to the possibility of dimensions that aren’t experienced by the five senses. An integral part of this new culture is the budding spirituality of personal gnosis I mentioned above that uses pop culture stories of fully realized alternative worlds to spin new mythologies and inspire new spiritual practices. I believe the influence of these new pop mythologies, as they saturate our imaginations, may paradoxically begin to foster a more sophisticated consideration of spirituality in mainstream secular culture.

I think we live in the most exciting of times, at the beginning of a century where mystical and rational ways of knowing have the potential to approach the equal footing they once had in the Renaissance. Neither way of thinking is right or wrong in itself; they cover completely different territories. But sparks fly when one doesn’t completely squash the other and they are forced to rub up against each other out in the open.

TheoFantastique: I was struck by this statement in your book: “The cultivation of feelings of terror or dread in the face of evil forces serves as a flawed vehicle to the transcendent – a dark transcendent shorn of the larger metaphysical context that embraces the divine as well as the demonic.” In my view there tends to be a dualistic dynamic in relation to such things, and conservative Christians in particular tend to sanitize their views on such things so as to embrace the divine and the light but to the neglect of the darkness. How does this observation connect with some of what you were trying to get at in this section of your book?

Victoria Nelson: I’d distinguish here between orthodox religious doctrine and types of alternative spirituality that get activated from the imaginary worlds of individual writers and filmmakers. Christianity contains within it the light and the dark in equal measure, but conservative Protestant Christians especially tend to put an emphasis on the Devil’s side of things, as witness the very popular Halloween “Hell Houses” I talk about in Gothicka. When I speak of “the cultivation of feelings of terror or dread,” I refer to the sensations one has on reading a horror story or watching a horror film — until recently the only kind of representation of the supernatural you could experience outside a church, temple or synagogue — as a weird kind of repressed and rather negative religious experience. And weird and rather negative because of the centuries-old link between the supernatural and the Devil in our culture. Some people — not everyone — take this feeling farther and turn it into a religious practice based on the story or film they consumed.

TheoFantastique: The tendency of many, whether academics or religious conservatives, is to ignore or dismiss the Gothick in pop culture as “low brow,” or an inappropriate vehicle for consideration of the transcendent. Why have you interacted with these elements so positively as elements of the sacred?

Victoria Nelson: Great religious shifts tend to come from below, from a common sentiment that reaches a kind of critical mass, which is then catalyzed by a leader who emerges seemingly from out of nowhere, not from a theological seminary. Joseph Smith, the founder of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints who was steeped in the popular folklore of his day, produced a narrative that situated Jesus Christ in North America. That twist filled a perceived need to update an Old World religion to a New World framework, and it doesn’t diminish the Mormon contention that this information was divine revelation to say so.

Victoria Nelson: Great religious shifts tend to come from below, from a common sentiment that reaches a kind of critical mass, which is then catalyzed by a leader who emerges seemingly from out of nowhere, not from a theological seminary. Joseph Smith, the founder of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints who was steeped in the popular folklore of his day, produced a narrative that situated Jesus Christ in North America. That twist filled a perceived need to update an Old World religion to a New World framework, and it doesn’t diminish the Mormon contention that this information was divine revelation to say so.

TheoFantastique: In your chapter on Gothick Gods you discuss the significance of the mythic narratives of horror and science fiction, as well as those who consume such things in the categories of fans and believers. How are these fantastic myths fueling the imagination in ways that blur the lines between imagination and belief, fans and believers?

Victoria Nelson: Fan culture is a very broad continuum these days. I divide it into the categories Consumer, Performer, and Believer. It’s important to note that there’s not necessarily a slippery slope from one category to the next.

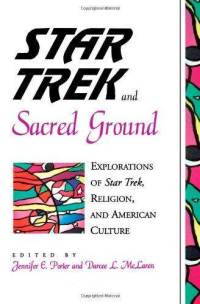

Consumers consume and enjoy. Performers take it a step farther into interactivity. They write fan fiction based on the fictional works they love or take on the identities of favorite characters at conventions, film premieres or other gatherings (for instance, the summertime “orc” meetings in Sweden). Extreme Performers are fans like those Trekkers who adopted the characters’ identities in daily life, either as Klingons speaking that invented language or as Star Fleet officers in uniform, living their daily lives within the code of behavior they see as governing them. Same with the Na’vi kinfolk out of Avatar. They adopt a fictive identity and engage in a lifestyle practice that is primarily ethical, not spiritual.

Believers, finally, are those who resonate so deeply with certain books, TV shows, or movies that they form a spiritual practice for which the fiction serves as a kind of scripture. The Church of All Worlds, founded more than forty years ago, is based on Robert Heinlein’s sci fi novel Stranger in a Strange Land. Many groups and individual practitioners base their spiritual practice on the imaginary universe of H. P. Lovecraft. Most recently, a small group of “Cullenists” profess that they worship the vampire Cullen family of Twilight as gods and read the four volumes of the series randomly every day as a form of spiritual practice. And there are many other examples, most of them Christian influenced in one way or another.

TheoFantastique: Although I am not a fan of Twilight, I found your discussion of this and paranormal romance of interest. How has this series of novels and films helped construct a new Dance with Death, the divine feminine, and human deification?

TheoFantastique: Although I am not a fan of Twilight, I found your discussion of this and paranormal romance of interest. How has this series of novels and films helped construct a new Dance with Death, the divine feminine, and human deification?

Victoria Nelson: What I found fascinating in the Twilight novels, besides a compelling love story very much in the Gothick tradition of Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre, was the rich strand of Western esoteric traditions that Stephenie Meyer reflects in her novels. Bella, the human girl who decides she must become a vampire to be a fit partner for her vampire lover Edward, actually becomes the Bride of Death — a very ancient pancultural myth. Like the Christian Mary, she births a half-human, half-immortal child (in this case, a girl, not a boy!). Like Jesus, Bella suffers her own harrowing of hell, a three-day sensation of unbearable burning, as she turns into a vampire. Once she’s a vampire, she enters a world of immortal beauty and perfection—these are abstinent vampires, remember, who have overcome their lust for human blood — where she has superpowers of every imaginable sort as well as immortality. Theosis, the idea that humans can become gods on a par with Jesus after death, is an important Mormon doctrine that I suspect Meyer, a Mormon, may have drawn on in creating her beautiful, beneficent godlike vampires.

So the Twilight series is a great example of the evil-becomes-good turn in Gothick supernatural narratives at the end of the 20th century. This is the big, big shift at work in this new century and it has profound implications. Somehow the collective imagination has gotten to work on these dark Gothick narratives and brightened them, and that broader, sunnier framework is what has allowed these stories to start working as scripture, as the basis for a spiritual practice for more people.

The hunger for some kind of transcendental worldview or experience people outside organized religion feel is immense, it can’t be underestimated. If they only find the non-material, the supernatural, in stories of evil spirits, they are going to start working on that to make it work for them! Out of all humankind, only a very few want to worship the God of Darkness. The big trend is now to open the door and let some daylight in. Repentance and salvation are open to every creature in the Gothick universe today, even zombies. Why worship Dracula if you can pray to Carlyle Cullen? Why not worship a reformed immortal vampire?

TheoFantastique: You may recall from our last discussion on Guillermo del Toro that I am a huge fan of his work. Although he professes skepticism, how do you see his work as exhibiting the monstrous sacred as a spiritual reality?

Victoria Nelson: Del Toro professes skepticism around the religion of his birth, Catholicism, but not around the existence of other dimensions or realms beyond the material. He has famously stated that his main character Ofelia of Pan’s Labyrinth is not fantasizing her world of fairies — one possible interpretation of that story — but is perceiving a fully blown spiritual reality.

Victoria Nelson: Del Toro professes skepticism around the religion of his birth, Catholicism, but not around the existence of other dimensions or realms beyond the material. He has famously stated that his main character Ofelia of Pan’s Labyrinth is not fantasizing her world of fairies — one possible interpretation of that story — but is perceiving a fully blown spiritual reality.

He also admits the deep influence medieval Catholicism has had on him, from the bestiaries of fanciful creatures to gargoyles and other religious images. He has created a unique and distinctive mythic pantheon assembled, personal gnosis style, not only from Catholic iconography but also from a mélange of other influences ranging from Celtic mythology to Mexican folk creatures to Lovecraftian monsters. And his two Hellboy movies, adapted from the Mike Mignola graphic novels, present yet another half-human, half-supernatural character who comes from a dark place (hell, in this case!) only to become a good guy. But he doesn’t like nice vampires particularly. In that subgenre he’s still very much on the dark side.

So del Toro’s hybrid imaginary universe certainly contains monsters, but whether it also holds the possibility of the sacred is up to him to tell us. I don’t think he has yet.

TheoFantastique: In the Los Angeles Review of Books analysis of your volume, Mark McGurl asked his readers to assume atheism and materialism, and then proceed to engage your book as flawed in interpreting the Gothick. For him one of the problems is that this supernaturalism ignores atheistic realism. I have seen similar debates where those from a skeptical orientation assume the nihilism of horror and find its connection to the sacred improbable or impossible. How would you respond?

Victoria Nelson: As a writer, I am always happy when a reviewer shows he has read my book all the way through and attempts to address its arguments seriously. That was the case here. A belief system is a belief system, however, whether it’s spiritual or atheistic. I presented a cultural phenomenon, and out of his own belief system this reviewer conflated the phenomenon with my presentation of it. You can argue against an interpretation, as he does against mine, but not a phenomenon.

TheoFantastique: Victoria, thank you again for this discussion and your book. I hope it gains a wide readership and lots of discussion.

2 Responses to “Interview with Victoria Nelson on Gothicka: Vampire Heroes, Human Gods, and the New Supernatural”