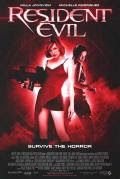

Paul Teusner is another Australian “mate” of mine. I first encountered his work through an intriguing paper he wrote on horror and religious identity. Paul has experience in research and writing for Christian ministry work among youth, and is working through post-graduate research on religion in cyberspace. Paul’s paper that I encountered is titled “Resident Evil: Horror Film and the Construction of Religious Identity in Contemporary Media Culture” that was written as part of his Master of Theology at Melbourne College of Divinity in 2002. As the title of his paper indicates, his thesis brings together issues related to religion, horror, religious identity, and the significance of the media to these issues. Paul has agreed to share his thinking with us.

Paul Teusner is another Australian “mate” of mine. I first encountered his work through an intriguing paper he wrote on horror and religious identity. Paul has experience in research and writing for Christian ministry work among youth, and is working through post-graduate research on religion in cyberspace. Paul’s paper that I encountered is titled “Resident Evil: Horror Film and the Construction of Religious Identity in Contemporary Media Culture” that was written as part of his Master of Theology at Melbourne College of Divinity in 2002. As the title of his paper indicates, his thesis brings together issues related to religion, horror, religious identity, and the significance of the media to these issues. Paul has agreed to share his thinking with us.

TheoFantastique: Paul, not a whole lot of graduate students working their way through a masters degree in a divinity school are drawing upon the types of subject matter you chose. I find this refreshing, but what in your background and interests might have helped shape you in moving in this direction?

Paul Teusner: In my undergraduate degree I did fairly well in Biblical Studies and Practical Theology, but only just made it through the Systematic Theology subjects I had to endure. There was something about the nature of those courses which made me think it was an exercise in placing God on some sort of theoretical flow-chart. I realised that my present and future ministry with people would never involve any of the language that was employed in those courses, and I guess I found the whole exercise quite alienating for myself. So rose my interest in finding out what language ordinary people, and in particular young people, use to talk about God, faith and organised religion. I was particularly keen to explore where people find the tools for religious expression and imagination. So I turned to horror film as an example, knowing that in this popular film genre, perhaps more than any other, explicit religious themes are explored.

TheoFantastique: You begin your paper with a discussion of culture and then you connect myths and rituals in this context as cultural mechanisms. Can you briefly summarize some of your thinking here?

Paul Teusner: I don’t think I can, but I’ll give it a shot. I believe that cultures and subcultures are formed by stories (myths, histories, popular narratives) and communal acts that connect us to those stories (that we call rituals). A useful example for us Aussies is the story of Gallipoli, where in World War I Australian and New Zealand troops were sent on a mission to defeat the Ottoman army that was doomed to fail. Our knowledge and respect for what happened on that day in history is an especial component of what makes us Australian. The Anzac Day march is a cultural act that reconnects us to the communal memory of that day, where we make present a time gone-by, and express our hopes for a future without war. The ritual is the act that connects us to the myth or the story, and reinforces our identity as a people who own and are made by that story. So rituals and myths are used to construct a communal identity and our belonging therein.

TheoFantastique: So then you see horror, science fiction, and fantasy films as serious expressions of the mythic and the ritualualistic, and therefore these are more than just entertainment and in many instances, they represent important cultural and religious components for us to understand?

Paul Teusner: I think these popular movies tend to reinvent some of the stories that have existed in cultures all around the world, but that may have been marginalised by secular liberalism that has dominated modern Western culture. These movies point to ancient ways of seeing the world, but using contemporary symbols, characters and language. the cultural significance of these films are always underpayed by mainstream society, but you only have to spend some time in the “cult” section of your video library to see members of subcultures that have been formed by these films, attesting to their power to reconstruct notions of cultural identity.

TheoFantastique: In my own research I have drawn upon the work of the late anthropologist Victor Turner in relation to his concept of communitas. How has his work, and that of others, helped you understand ritual, myth, its connection to mass media, and how this is significant for culture today?

Paul Teusner: Turner’s notion of comunitas has been extremely helpful for my understanding of popular myth and ritual practice. For Turner, a ritual is an act which has relatively little practical use (unlike a “habit” which is something you perform every day, like shaving, but is done to for other reasons besides) compared to its symbolic significance. A ritual practice is the making of the doorway between the societas (ordinary world) and the comunitas – the world of the mythic, full of possibility and imagining. For example, Christian Eucharist is more than giving thanks to God, but in participating in the ritual we endeavour to create, for a moment, a community of people who are in full connection with God. In doing it Christians remember and relive the history of Jesus who lived that life, and remind themselves that in the future the possibility will be realised. The ritual makes past and future imaginings actualised. Pierre Babin offers a useful understanding of rituals, as those practices where the a communication of myth – something that reveals the essence of life, an emergence of identity or a flowering of conscience, and a communication of something that connects with a deep consternation or aspiration for life. This definition is useful as it reveals how symbols and narrative structures in film can be seen as ritual processes.

TheoFantastique: How is horror a “ritual activity?”

Paul Teusner: I believe audiovisual media are replacing some of the common rituals in contemporary popular culture, but more than that, I think most popular films follow a common narrative structure that involves their audience in a ritual process – portraying an ordinary or slightly idyllistic world, then introducing an evil that threatens the stability of that depicted world, and then the battle of good vs evil begins. Audiences leave the film recognising that the world, though returned to its former stability, is to be seen in a different way, through different eyes, with new or renewed values. This, I think, is the goal of any ritual – to leave and return to the ordinary world with a refreshed understanding of it, and our place in it.

TheoFantastique: What do you mean when you refer to a sense of “religious identity,” and how do horror films and other forms of mass media play a major role in the construction of this identity?

Paul Teusner: In the modern era “religious identity” generally referred to what religious group or denomination you belonged to. “I’m Jewish” or “I’m Presbyterian” would pretty much cover it. I believe the postmodern era is characterised by the disregard of these labels, and the accompanying demise of authority of religious institutions. I think nowadays religious identity has become an individual pursuit, that’s marked by phrases like “I’m not religious but…” or “I’m Catholic, but I don’t go for that stuff anymore”.

I think the stories that are retold in popular media offer us the tools, the language to be able to express and communicate our understandings about the origins of life, the presence or absence of a supreme being, the meaning of life, what we’re meant to do, etc. For example, young people I have interviewed have suggested that The Matrix, while not purporting a reasonable view of the real world, makes them think about forces in life that we can’t see, and helps them appreciate how to be sensitive to our definitions of “reality” and that there are countless alternative depictions possible.

TheoFantastique: In the late 1960s Harvey Cox spoke of human beings as homo festivus, given to festival and revelry, and homo fantasia, the “visionary dreamer and mythmaker.” He also spoke of Western culture at this time as being fantasy deprived. This may still be true, and with special application to the church. In your paper you select nine films and then us them as a means for engaging in a theological conversation as to how they impact religious identity. Do you think there is a significant place for fantasy, science fiction, and horror genres to inform the theological imagination, conversations, and reflection of the church in the West?

Paul Teusner: In the third year of my undergraduate studies I took a course titled Theological Reflections in Ministry, where a couple of weeks was spent talking about the nature of theological imagination, and the place of imagination in theological inquiry. I have to say the conversations surprised me, in a college that had placed so much importance on rational, theoretical approaches to theology. But it was a liberating exercise – to appreciate how the human mind can imagine future possibilities, and the responsibility of those in ministry to respect them and things of God. I was reminded that God has spoken to many in the Bible in dreams, and that Isaiah calls all to hope where dreams and visions thrive. So I definitely believe there’s a place for fantasy in theology, but I believe it’s been surpressed by mainstream Protestant institutions where only the academes survive. I would contend that any endeavour to engage in mission in contemporary media culture will necessarily involve embracing imagination as a tool of theological inquiry.

TheoFantastique: You also speak of theology as mythic, marginal, and as genre. Can you briefly summarize your thinking here?

Paul Teusner: In my paper I call readers to consider the parables of Jesus as retold in Luke. In these parable grand theological treatises about the nature of God and God’s desires for people were told using symbols and structures that were commonly used by the people of the time. The telling of these parables was in itself a political rebellion against the intellectual elite among the Jews and Romans. It was a marginalised form of theological communication. But the process of engaging with an audience through parable – presenting an ordinary world, then presenting a subversive influence to produce a new moral or value through which to see the world – is both an act of genre and an act of theology. Jesus’s relationship to his audience, as Luke’s relationship to his readers, involves all three aspects in the construction of a theology – myth, marginalisation and genre.

TheoFantastique: In your discussion of theology and religious identity you state that “visual and performance arts, over time, became a secular pursuit, away from the sanctions and supports of the Church.” How might the church begin to embrace these missing facets of expression and do so as part of the sacred realm?

Paul Teusner: Oh, man. If I knew I would be getting fat off the royalties of my book! Taisto Lehikoinen has written much on how different churches have engaged with contemporary media, and all have failed in some way. I would say at this time all endeavours are experiments, and most would cause tensions with those who hold to the tried-and-true ways of doing things. Essentially I believe it will really only be successful in the local setting, whether that be the small community church, Internet chat room or out the back of your local pub or coffee shop. What “the church” will do will depend on how well “the church” listens to the rebellious, curious, tentative and timid expressions of itself on the cusp between religious institution and local culture.

TheoFantastique: Finally, Paul, you state that “just as the printing press fuelled the Protestant Reformation in 16th century Europe, so audio-visual communication presents a challenge to established religion in this time.” You also state that “horror film, as much as all other forms of audio-visual media, present a new forum for theological discourse that impacts on Christian life.” Would you say that the cultural situation in the West makes this an ideal time for Christian storytellers, mythmakers, and filmmakers to get involved in producing good horror, science fiction, and fantasy?

Paul Teusner: Only if they have the money, unfortunately. We live in an era where media is controlled by the corporation. I believe that the Internet is offering a place for new and challenging uses of media are made available to more people. At the moment, Christian storytellers and film-makers should make the most of web sites like YouTube and myspace.com to connect with an audience and make their presence known.

TheoFantastique: Paul, thanks for your paper, and thanks as well for making the time to share some of your thinking with us.

Paul Teusner: No problem, mate. I appreciate your reading of my paper and thank you for making it known out there.

Looking at the list of films, none of which I have ever seen, most look like science-fiction even more than they are horror.

Perhaps I’m really out of touch with pop culture!

Sometimes the line between science fiction and horror is blurred these days, Steve, but this is not necessarily anything new. My wife recently gave me a Creature From the Black Lagoon trilogy collection and as I watched the extras someone commented on these films as science fiction. Usually they are classified as the last of Universal’s classic horror monsters. Don’t worry about the confusion!

Hey Steve,

About half would be classified as sci-fi horror … I’m about as big a sci-fi fan as I am a horror fan.