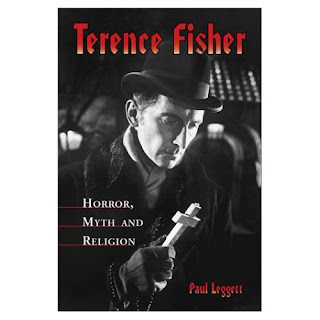

Paul Leggett is one of the most interesting and unique Presbyterian pastors around. In fact, it has been said that Paul is probably the most knowledgeable Presbyterian pastor on horror films that one can find. I first met Paul at Cornerstone Festival in the Imaginarium, and have had the pleasure of hearing his insights on a number of films. Paul is Pastor of Grace Presbyterian Church in New Jersey, the author of a number of articles Sherlock Holmes, horror films (particularly Gothic horror), and is the author of the book Terence Fisher: Horror, Myth and Religion (McFarland & Company, 2002). Paul has graciously taken a few moments from his pastoral responsibilities to share his thoughts with us.

Paul Leggett is one of the most interesting and unique Presbyterian pastors around. In fact, it has been said that Paul is probably the most knowledgeable Presbyterian pastor on horror films that one can find. I first met Paul at Cornerstone Festival in the Imaginarium, and have had the pleasure of hearing his insights on a number of films. Paul is Pastor of Grace Presbyterian Church in New Jersey, the author of a number of articles Sherlock Holmes, horror films (particularly Gothic horror), and is the author of the book Terence Fisher: Horror, Myth and Religion (McFarland & Company, 2002). Paul has graciously taken a few moments from his pastoral responsibilities to share his thoughts with us.

TF: You have a special interest in Gothic horror. Why does this form of horror most interest you as opposed to other expressions?

Paul Leggett: Gothic horror has most appealed to me because it is the closest artistic form to the biblical picture of the conflict between good and evil, God and Satan. If the fundamental struggle of life is spiritual (Eph. 6:12) then the classic stories of Frankenstein, Dracula, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, etc. give best expression to that reality using symbol and myth.

TF: Have you ever preach any sermons based upon this material? If so, I’d love to hear them!

Paul Leggett: I’ve preached a lot on these subjects. It’s unavoidable. That however is nothing new. When Robert Louis Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde was first published it was the subject of sermons all over England.

TF: Can you briefly sketch the origins and development of Gothic horror from literature to film by noting some highlights for us?

Paul Leggett: The Gothic horror story actually begins as a reaction against the extreme rationalism and overconfidence of the Enlightenment of the eighteenth century. The first so-called Gothic novel was The Castle of Otranto (1764) by Hugh Walpole. It introduced the classic elements of a dark sinster castle, evil villains, terrified heroines, brave heroes, ghosts and supernatural events. There were many early such novels, some being overtly supernatural (M.G. Lewis’ The Monk), others appearing to be supernatural but actually the activity of evil human figures (Ann Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho). In the nineteenth century the influence of gothic horror can be seen in such classic novels as Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey, Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights and Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre. In 1818 Mary Shelly writes the most famous gothic horror story, Frankenstein and the rest is history.

TF: Why do you see Gothic horror as relevant and import both for contemporary evangelicals, and for the period of late modernity or post-modernity in which we live?

Paul Leggett: Gothic horror is important for evangelicals because it presents an essentially Christian worldview. In some cases , like Dracula and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde this is very explicit. It generally has an orthodox view of human nature, sin, and redemption. Because the Gothic horror story is a reaction against early modernity it relates well to the post-modern. It challenges the assumptions of modernism. It is interesting to reflect that we remain fascinated by these stories and they are still being dramatized in the twenty first century.

TF: Let’s move to a discussion of director Terence Fisher and his Hammer films, some of my favorites. When were you first drawn to an interest in Fisher’s work?

Paul Leggett: My first Fisher film was The Hound of the Baskervilles. I was (and am) a huge Sherlock Holmes fan so I insisted my parents drive me to a theater where it was still playing after we had returned from summer vacation. My initial reaction was negative. It was so different from the Basil Rathbone films. However when I saw it again later on television I realized what a great film it was. The first Fisher film that excited me immediately was The Brides of Dracula.

TF: The subtitle of your book on Fisher is interesting, where you connect his depiction of horror to myth and religion. How do you make this connection?

Paul Leggett: Horror, myth and religion overlap everywhere in ancient myth, the Bible, Shakespeare’s plays, classic horror stories, films, etc. The Bible actually has more monsters in it than any other book I can think of. Literalists sometimes want to play this down but they then miss a critical theme. For example, Jonah isn’t swallowed by a whale but by a sea monster (Matthew 12:40).

TF: The Epilogue of your book is titled “The Lessons of Horror: Terence Fisher in Context.” What might the informed viewer take away from Fisher’s depiction of horror in terms of religious and thematic elements?

Paul Leggett: The dominant theme of Fisher’s films is the power of the cross. This power is independent of humans. The cross in his films has a life of its own. It often emerges out of ordinary things like candlesticks and windmills. The cross is the ultimate symbol for Fisher of the power of good over evil. His fundamental message is that good ultimately conquers evil and this good is often depicted in Christian symbols. Fisher also emphasize the idolatry and inevitable destruction of human pride. This is a key theme in his Frankenstein series. These are the central themes that I think emerge for a viewer of Fisher’s work.

TF: You also conclude your book with the statement that “the horror film bears study as a symbolic statement of the spiritual crisis of Western culture.” What do you mean by this, and how might Christians draw upon the horror film as a product of culture that informs our understanding of the culture, its hopes and fears, and the key issues related to religion and spirituality?

Paul Leggett: The horror film gives us an insight into the spiritual condition of our culture. This has been true for almost a century. The nature and tone of horror films reveal the outlook and fears of the culture. A classic horror film like The Black Cat (1934) tells us more about the lingering mood of World War I for example than any overt war picture of the period. Unfortunately, we now live predominantly in an age of nihilistic horror where evil is often triumphant. Nonetheless the continuing interest in gothic horror gives us a point of response. The most recent version of Dracula contains both classic gothic themes and the post-modern view of the invincibility of evil. The fact that it is Dracula however still provides us with a Christian context for discussion and hopefully, witness.

TF: Paul, thank you so much for sharing your insights. I hope you continue writing and sharing your expertise at Imaginarium for years to come.

There are no responses yet