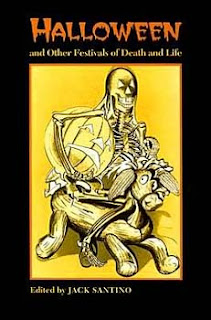

Dr. Jack Santino is a professor in the Department of Popular Culture at Bowling Green State University in Bowling Green, OH. His academic work has included an analysis of the cultural meaning of holidays and festivals. Among his many publications is the book Halloween and Other Festivals of Death and Life (Knoxville: University of Tennessee, 1994) which he edited. As the Halloween season approaches, the second largest holiday in retail sales in the U.S., we are privileged to have Dr. Santino provide his perspective on this interesting holiday.

Dr. Jack Santino is a professor in the Department of Popular Culture at Bowling Green State University in Bowling Green, OH. His academic work has included an analysis of the cultural meaning of holidays and festivals. Among his many publications is the book Halloween and Other Festivals of Death and Life (Knoxville: University of Tennessee, 1994) which he edited. As the Halloween season approaches, the second largest holiday in retail sales in the U.S., we are privileged to have Dr. Santino provide his perspective on this interesting holiday.

TheoFantastique: Dr. Santino, thank you for making time to share your research with the readers. Let’s begin with a little background on you. Where did you do your studies, and how did you end up teaching academically in the area of popular culture?

Jack Santino: I grew up in Boston and attended Boston College, but I really wasn’t too interested in academics. On my own, however, I had a great interest in folklore and mythology, as well as what we now call popular culture, particularly comics and rock’n’roll. Two years after I graduated I found out that there were graduate programs available in folklore. I applied to a couple, and I attended the University of Pennsylvania’s Graduate Department of Folklore and Folklife, where I got my Ph.D. From Penn I took a job at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, where I worked on the Annual Folklife Festival, and after 8 or 9 years I responded to an ad for a teaching position in the Department of Popular Culture at Bowling Green State University.

TheoFantastique: What contribution do the perspectives of festival and Folklore studies bring to an understanding of Halloween?

Jack Santino: As you mention, Halloween has become a major annual festival in the United States, and the American-style version of the holiday is being introduced abroad as well. Folklore helps us understand the customs and symbols that are central to the occasion, and how we received or inherited them. But as a discipline, Folklore is not only about the past. These customs and symbols are fluid, as are their meanings and the ways people use and understand them. I got interested in writing about Halloween because I enjoyed it as a child, but also because I could see it changing all around me. The rise of grown-up masquerade parties, the explosion of elaborately-decorated homes, and city-sponsored festivals — none of these were a part of my childhood experience. So I wanted to document and try to understand the change in Halloween from a child-oriented event to a more inclusive and multifaceted one. The study of ritual, festival, and celebration offers concepts for understanding large public events such as Halloween. The idea that there are certain periods when the everyday rules are meant to be broken is one. Also, the idea that during times of transition (in the life cycle or seasonal), all bets are off–the dead can mingle with the living; children are allowed to demand treats from adults, people dress in special costumes; things are turned upside-down and inside-out. These ideas help us to see Halloween for its importance. It is a time when we face our taboos (death being a major one) and playfully accept them as part of life.

TheoFantastique: From my research, including the book you edited on the topic, I know that Halloween has a long and continually evolving history and variety of influences. But can you summarize it for us as to where its roots may be traced, some of the key influences, and how it arrived at its present form in the U.S.?

Jack Santino: It is generally accepted that the most influential forerunner to Halloween is the Celtic festival of Samhain (pronounced “Sawin”). The Celts were the ancestors of today’s Irish Welsh, and Scottish, among others, and Samhain, on November 1, was both the first day of winter and the first day of the New Year. It was believed that the souls or spirits of those who had died during the year previous were now allowed access to the world of spirits. So spirits were wandering on the eve of Nov. 1, and people would leave their fires lit and put food and drink on the table for any family members who happened by. Ireland was converted to Christianity in the early centuries of the first millennium, and the Christian church tended to believe that people who held non-Christian beliefs had been deceived by the Devil. So the idea of evil was added into the mix. Eventually, the church set the Feast of All Saints, or All Hallows on November 1, and October 31 was known as Hallo Even, or Hallowe’en.

TheoFantastique: Unfortunately, many fundamentalist and evangelical Christians tend to focus on the Pagan origins and elements of Halloween to the exclusion of a variety of other elements, while also ignoring the continually evolving nature of the holiday as it takes new forms and meaning in American culture. How would you respond to this narrow interpretive lens through which some view the holiday?

Jack Santino: I understand people’s objection to Halloween insofar as they believe strongly in the existence of a literal Devil who is engaged in an effort to steal our souls. But I was raised in a religious atmosphere where that simply was not a problem with the celebration. I tend to view it as a healthy occasion for the parading and confronting of aspects of life — symbolically — that we usually pretend don’t exist. Also, Halloween is tied closely to harvest imagery, and I think the lesson is that, as the natural world faces death as a part of ongoing life, so must we. Halloween is many things. It allows us to mock our fears, and to celebrate life. There is room for parody and topical satire in the costumes and displays. But it also deals with deeply important issues involving life and death, nature and culture.

TheoFantastique: What does the increasing popularity of Halloween say about Americans if we understand Halloween in part as a vehicle “for the expression of personal, social, and cultural identity?”

Jack Santino: I think a lot of the popularity of Halloween is due to the maturing of the baby-boom generation. People who had fun after WWII and in the 1950s and 1960s seem to have decided not to give this up. In addition, the U.S. is a consumerist society. I have noticed that when people start to do something en masse, commercial entities jump on it pretty quickly. So when people started decorating with homemade dummies, it wasn’t long before mass-produced Halloween figures began to appear in the department stores. Likewise, as people began decorating more elaborately for the autumn season, electric outdoor lights, similar to those of Christmas, were offered.

TheoFantastique: How does Halloween compare with similar festivals and celebrations in other cultures?

Jack Santino: Halloween compares in a couple of ways. Many countries observe Halloween; it was very popular and important in Ireland long before it was widely-known in the US. Most Catholic countries observe certain rituals and customs for All Saints Day and also All Souls Day on November 2. These may involve visiting the family graves, for instance, and not resemble the current American Halloween at all. We are becoming increasingly aware of the Latino Day of the Dead celebrations (Dia de los Muertos), which are reminiscent of the U.S. Halloween in some ways but very different in others. On the other hand, many countries have celebrations that are reminiscent of Halloween but are different occasions, such as Walpurgisnacht in Germany (May 1). And the way Halloween is celebrated in street festivals in the U.S. reminds me of Mardi Gras in Louisiana and elsewhere.

TheoFantastique: Some scholars have applied the work of anthropologist Victor Turner and his notion of liminality to Halloween. Might the process of entering a liminal space and engaging in costuming as a process of social inversion in some instances account for the popularity of Halloween among adults? I was surprised to find the holiday and related items, like the haunted attraction industry, to be huge in Utah after my relocation from northern California. This is a religiously and culturally conservative state, and might the aspect of liminality and social inversion be part of the appeal in this state’s context?

Jack Santino: Yes, I think there is enormous appeal to adults to being allowed in this period of license to break everyday social rules. I see people working in banks on Halloween dressed as moose. I see grown-ups turning there homes into haunted houses and actually scaring children. I see people who keep their front yards impeccable and the lawns trimmed to the appearance of a golf course put fake gravestones and hang ghoulish monster on their property. At any other time of the year they would have the police at their door. But at Halloween, they have friends and neighbors congratulating them on their creativity.

TheoFantastique: Dr. Santino, thank you again for taking the time to share your thoughts. I hope the readers will pick up a copy of your book on the topic so that they will have a broader understanding of the history and multicultural influences of Halloween as we near the month of October.

3 Responses to “Jack Santino: Halloween, Folklore, and Death Festivals”