Normally my family opens Christmas presents on Christmas morning, but after weeks of pressuring and begging by our two teenage children, my wife agreed to a gift opening on Christmas Eve. This left us free to sleep in a little on Christmas morning, and after breakfast we went to the movies to see I Am Legend starring Will Smith.

Normally my family opens Christmas presents on Christmas morning, but after weeks of pressuring and begging by our two teenage children, my wife agreed to a gift opening on Christmas Eve. This left us free to sleep in a little on Christmas morning, and after breakfast we went to the movies to see I Am Legend starring Will Smith.

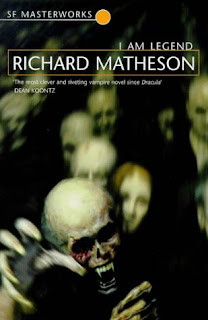

This film represents the latest cinematic treatment of Richard Matheson’s book I Am Legend published in 1954. In a story that has entertained readers and viewers for over fifty years, it is no surprise that it has resulted in three films formally based upon it, has influenced other films such as 28 Days Later, another film produced as straight-to-video, and has also resulted in a graphic novel.

I enjoyed the previous film versions of this story, especially The Last Man on Earth from 1964 starring Vincent Price, but was less pleased with 1971’s The Omega Man starring Charleton Heston. Like any cultural artifact, each film should be understood as a reflection of its times, including not only its choice in stars, but also its treatment and adaptation of the story’s subject matter. Each of the story’s incarnations demonstrate similarities and difference as the main character deals with an apocalyptic scenario that leaves him (to the best of his knowledge) as the world’s lone survivor after a viral or biological phenomenon kills the vast majority of humanity, and turns the rest into a collection of vampire-zombie-like mutants intent on killing the living.

Having recently watched both the 1964 film as well as the latest version, I was struck by the contrasts. In both films the main character seeks to use his immunity to the plague or virus to cure humanity, but in the current film there is a much stronger emphasis on this desire. This is connected to an important story element where Will Smith’s character, Robert Neville, is a high ranking Army medical officer who contributed to medical work on a genetically altered form of a measles virus used to treat cancer which eventually mutates bringing humanity to the brink of extinction. Smith’s character thus has a stake in setting things right, and there are a number of times where he states that he wants to stay in New York at this apocalypse’s “Ground Zero” in order to “fix this.” Another difference is the main character’s daytime efforts at stalking and killing the vampire-like creatures in the 1964 film, whereas Smith’s character largely avoids the creatures in an attempt to survive, even while capturing the creatures from time to time in order to conduct human trials on various vaccines he is experimenting with.

I Am Legend taps into several contemporary fears of late modern Westerners, such as apocalypticism at our own hands, genetic engineering gone awry, widespread death by disease, fears of loneliness, societal breakdown and the resulting massive chaos, and questions about meaning and purpose in response to an apparently nihilistic and godless universe.

The most significant issues for me in this film were the notions of loneliness and the need for human social interaction, order versus chaos, and the question of the meaning of life and God’s (non)existence. As the film develops the viewer comes to understand how Neville continues to deal with the challenge of being the lone human survivor. Two elements are most striking here. In the first Neville sets up manikins in a video store he frequents, going so far as to interact with them verbally each time he goes to the store to borrow a video. The second element that exemplifies Neville’s struggles with loneliness is his touching relationship with his dog Samantha (Sam). I don’t want to spoil any plot lines for those who have not seen the movie yet, but as the film develops it is a breakdown in Neville’s ability to deal with his loneliness as illustrated with these examples that becomes an almost fatal weakness.

Another striking element of the film is the issue of order versus chaos. As we watch Neville go through his daily routine it becomes apparent that he is a very orderly person. He arises each day to an alarm at the same time, accomplishes various tasks at home and in his explorations of New York, only to return to his home and laboratory by alarm each evening. The order and routine of Neville’s life is a stark contrast and response to the chaos and disorder which now characterizes his post-apocalyptic world. His orderly life provides a means for him to survive and to retain his sanity in the face of the chaos that threatens to engulf him.

The way the film treats the issue of religion in the face of apocalypse and chaos is also interesting. This issue is addressed in both a general fashion and in Neville’s personal faith. In general, the issue of religion is touched on visually very briefly in the film when we first encounter Neville hunting deer in the vacant streets of New York. The camera pans across the empty city and we see a billboard plastered with a sign posted during the initial stages of the viral outbreak that reads “God still loves us.” The viewer has to pay close attention to various details in the city to catch this visual cue, but it seems to picture the efforts of some to retain the notion of divine love in the face of this growing tragedy, an item that takes on an even greater sense of urgency in Neville’s post-apocalyptic scenario.

The issue of religion is dealt with personally in the development of Neville’s life in response to the breakdown of society and his intense isolation and daily threat to life. Early on in the film, as the government and the military respond to the spreading virus, we see Neville praying in a traditional Christian type of prayer with his family. A little later when another character places blame for God on the virus and its spread Neville corrects them very pointedly with the words, “God didn’t do this. We did.” But toward the end of the film, in one of the more emotionally charged scenes, Neville has a dialogue with another survivor who finds him due to his daily radio broadcasts, and in this dialogue he states explicitly that for him God cannot exist in the face of such widespread death and suffering. There is the possibility that Neville recovers some form of faith at the end of the film in response to the prodding of his fellow survivor who encourages him to listen more carefully for the divine as she has done in finding Neville, but as Neville listens as he fights his nihilism it is the voice of his deceased daughter he hears guiding him. Is the viewer to understand that Neville has regained faith in the divine as he hears the voice of God speak through his daughter, or has Neville experienced only a partial ability to overcome his nihilism that places faith in love for family but nothing beyond this?

One other element of the film struck me after reflecting on a reader’s comment to this post, and that is the dynamics related to social groupings and the tendency to dehumanize “the other.” After an encounter with the mutants Neville makes the statement in his scientific notes that they have lost all connection with normal human social behavior. While this opinion might be understandable given his situation, it is inaccurate, and his misjudgment proves fatal to him by the film’s end. The mutants do indeed utilize a form of socialization, albeit a very different form than that which Neville enjoyed with pre-infected humanity. They care for each other in some sense and demonstrate anger and resentment at Neville’s continual capturing of various mutants for his clinical trials experiments. They also demonstrate intelligence, and use Neville’s attempts at maintaining sanity against him as he battles loneliness in the absence of his normal means of socialization through human to human contact. This interesting example of dehumanizing and demonizing of the social other in this film works in two directions as Neville assumes the mutants are now completely animal-like and unsocial, while the mutants assume Neville means them harm rather than good in his capturing of mutants for experimentation.

If I were to state a criticism of the film it would be in the treatment the film gives of the mutant humans infected by the virus. The critique here is twofold. First, the mutants suffer from our contemporary tendency to want things bigger and somewhat over the top. In this film the mutants are not only faster runners than average human beings, but they also possess incredible strength that goes beyond anything would normally associate with a human being, even those with a rabies-like infection that might tend to amplify rage and an adreline rush. The mutants were, in my view, too strong and too fast, thus dehumanizing them in some way, which makes it more diffuclt for the audience to empathize with them. Second, the computer generated effects were lacking. They appear mixed in effectiveness to this viewer, looking realistic with the recreations of deer, but looking far less so with their recreations of lions and the human mutants. I admit my bias here for physical effects, but I would have liked to have seen the filmmakers emphasizing physical effects for the mutants whenever possible and using CGI when necessary as a compliment to the physical. However, handling the speical effects for the mutants in this way would have been difficult given the incredible strength and speed required of them as discussed previously. But even with this criticism most viewers will likely be pleased with the special effects this film provides as a compliment to the psychological terror the scenario of the film presents.

While I Am Legend should largely be understood as holiday escapist entertainment (which should not be construed as diminishing its importance as a serious story or film), nevertheless it draws upon quality source material that taps into some of the deepest fears and anxieties of people living in the first decade of the twenty-first century. It provides another testament to the enduring ability of horror and science fiction to help us articulate and address these fears.

I really enjoyed the film. Will Smith carried the first 3/4 of the film by himself very nicely. He really captured the edginess, and angst I imagine is involved in extreme isolation. The film is also well done in that it doesn’t explain what it can show you. Most of the information we’re given about what has brought the Neville to this point is through what we see either through signs, flashbacks, or Will Smith’s acting.

However, I walked away from the film disturbed. It seems to me that Neville has no qualms killing those he is attempting to save. He loves humanity, but has little regard for these “sick” humans. If the film was framed differently he would be the villain, similar to “Vickie” in “I, Robot” who believes that some humans must die in order to save humanity.

What I took away from the movie was a man whose penchant for abstraction drove him to stay at “ground zero” and fix his mistakes he had made that affected the abstract humanity, continuing to do damage to most “humans” he came across. One could even make that case that with his continued pleas at the end to “let me save you” that the film is a twisted view of Christian evangelizing. He even sacrifices himself at the end to save the “us” of those who weren’t infected.

It’s obvious that these people who are infected aren’t the mindless monsters who are devolved socially as Neville sees them, but care for one another as seen in the one’s willingness to be exposed to sunlight, and their attempt to rescue the female taken by Neville. In addition it is clear they possess some level of intelligence in that they bait Neville in order to capture him (which he falls for).

The film sets up a very dualistic us and them framework for which Neville devalues the abstract them in order to save the equally abstract us. At any rate I’m not sure that this was the director’s intent, but the construct seemed as clear to me at least.

Jason, thanks for your thoughts.

Your comments were interesting and it provides an example of how viewers gain very different interpretations from the same film.

I did not see Neville as having “no qualms” about his killing in his attempts to create a vaccine to save humanity. Yes, the photos on his lab wall of human beings who died in the vaccine testing process were many, but recall that he first tried his experiments on rats until a promising cure possibility presented itself, he did indeed photograph his test subjects as human beings rather than merely record them as abstract numbers and test subjects, and rather than hunting and killing the mutants as Vince Price did in the 1964 incarnation of this film he spent a good portion of his time while purposefully statying in “Ground Zero” in order to try to save humanity. At the end of the film he gives his life in a final effort at doing just this. This seems difficult to recocile with Neville as a villain who cares little for his test subjects.

As to Neville’s efforts as an analogy to a negative form of Christian evangelism as you see it, I’d be interested in hearing an argument for this position which seems a stretch, and especially difficult to square with Neville’s shift from some from of religious faith to atheistic nihilism in response to the global apocalypse.

Thanks for this text, John! I had fears of people pickung the movie up the wrong way. It is easily imaginable that Ned Flanders, after watching I Am Legend with his kids, says to them: “And that’s what you get if scientists go meddling around with human life, kids. So what do you want to become?” “Preachers.” “Doodeligood!”

It’s like Hollywood often retreats to romanticism and never goes further along the philosophical development timescale.

Often I hoped that Nevill would say “Right, stop here.” and every cg effect, including the vampires, becomes technically visible, and he goes on rambling about questions of “Why would we do this movie? Why should we do it? What’s the fear about?” and goes out of the movie studio into labs and religions talking with people, stating things. …

I have the desire to recommend to you the book “Challenging Nature” by Lee M. Silver of 2006. It anticipates exactly this and explains, from the view of a very far-travelled molecular biologist, the fears arising in western Christian cultures in respect to new biotechnologies.

John, Thanks so much for hosting our Purple State event. It sounds like your questions beautifully framed the documentary. I’m with Craig. Wish you could come along.

In the meantime, I shared your appreciation of I Am Legend. I probably liked it more than most critics because I have such a long history with the original novella. But I also expected very little and came away surprised at how touhg-minded a piece of entertainment it turned out to be.