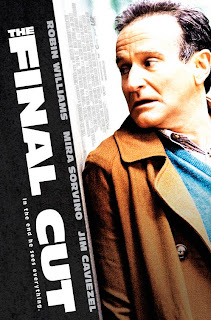

From time to time I try to do a little treasure hunting, not the kind where you dive deep below the ocean’s surface, or the kind where you use a metal detector and scan the sands of the beach, but the kind that can result in literary or cinematic treasures. Last week I engaged in a cinematic treasure hunt as I sifted through the discount video bin at Wal-Mart for DVDs of interest and purchased The Final Cut, a thought provoking sci-fi/thriller from 2004 starring Robin Williams. (See the trailer here.) This film was the brainchild of Omar Naim who wrote the screenplay and directed the film. The limited amount of special features with the DVD includes a “making of” segment where Naim mentions that he came up with the general idea for the story based upon his experiences in editing his documentary project. As he put it, “I really learned how manipulative the media can be, and how much you can transform truth and reality.” This insight, coupled with his curiosity about the background of his parents’ lives, provided the creative inspiration which led to the writing of what would become The Final Cut.

From time to time I try to do a little treasure hunting, not the kind where you dive deep below the ocean’s surface, or the kind where you use a metal detector and scan the sands of the beach, but the kind that can result in literary or cinematic treasures. Last week I engaged in a cinematic treasure hunt as I sifted through the discount video bin at Wal-Mart for DVDs of interest and purchased The Final Cut, a thought provoking sci-fi/thriller from 2004 starring Robin Williams. (See the trailer here.) This film was the brainchild of Omar Naim who wrote the screenplay and directed the film. The limited amount of special features with the DVD includes a “making of” segment where Naim mentions that he came up with the general idea for the story based upon his experiences in editing his documentary project. As he put it, “I really learned how manipulative the media can be, and how much you can transform truth and reality.” This insight, coupled with his curiosity about the background of his parents’ lives, provided the creative inspiration which led to the writing of what would become The Final Cut.

The story takes place in the near-future where parents with financial resources can choose to have their children receive a “Zoe implant,” a chip in the brain that grows with the individual and records every moment of their lives from the first person perspective. Upon the death of the individual, the implant is removed and the years of “footage” that can be edited with the help of surviving family members. There are a small number of people who do the editing, called “Cutters”, who putt together select life moments thus producing a film-like piece that is then viewed by family members and friends in a “Rememory” memorial service. Robin Williams plays a Cutter, Alan Hakman, who is known for the exceptional quality of his work, and also for his willingness to take on projects involving those who have lived less than exceptional lives and whose families want a life edit that presents the best possible Rememory for the individual. As the story develops we learn that Hakman struggles with his own troubling memories from his childhood, and his work on a client, an executive from EYE Tech that produces the Zoe implant technology, involves Hakman in dark memories and a life and death struggle with those opposed to EYE Tech and its impact on society.

Although this film involves an interesting scenario as its premise, and presents an interesting overall story, unfortunately it fails to deliver with its ending, and it left this viewer feeling let down as the many intriguing possibilities were left hanging by its disappointing conclusion. Nevertheless, for those who appreciate science fiction’s ability to present us with a medium for personal, social, and cultural reflection on significant topics of the day, and the critical distance by which to explore them, this film touches on several issues.

Subjective-objective frames of reference – In a scene from the film one of Hakman’s clients asks him if he changed the color of a fishing boat in his late brother’s Rememory that he recalls from a childhood fishing trip. While Hakman denies he’s changed the color and insists “I’d never do that,” this is contrary to the specific memory of the individual. In another scene Hakman revisits his own memory of a detail related to a negative childhood experience. It is Hakman’s faulty memory of this detail that contributes to his life-long guilt over the event. These scenes, as well as the overall thrust of the film, serve as a reminder not only of the faulty nature of our memories of the details of our experiences, but also contribute to our need to reflect on the distinction between the objective and the subjective, an issue of continuing debate in the shift from modernity to late modernity or postmodernity in the area of epistemology or how we know what we know.

Privacy – One of the key issues in this film is the issue of privacy in contrast with public knowledge. In one scene family members for one of Hakman’s clients are shown walking through a crowd of protesters on their way to a Rememory service. Many in the crowd hold up signs as they share their concern over the violation of privacy presented by the Zoe implants (with protest signs and fervor reminiscent of anti-abortion protests). Of course the concern over privacy as depicted in the fictional framework of Final Cut is a live issue in America with our cultural debates over rights to privacy in competition with private information being accessible to various government entities in a variety of contexts from surveillance cameras in public spaces designed to deter crime, to wire tapping of phone calls ostensibly to monitor potential terrorist threats.

Voyeur culture – This film also touches on America’s continued fascination with watching the “real life” experiences of the self and others. In the film this is depicted as the select editing of life experiences for a memorial experience, but this is not far from our current fascination with watching ourselves on so-called “reality shows,” to the uploading of the most mundane experiences on YouTube.

Religious dimension – Final Cut also includes a mild religious or spiritual dimension, and this aspect comes together with the elements referenced above in a scene between Williams and James Caviezel who plays Fletcher, a former Cutter who is now part of the anti-EYE Tech/Zoe implant protest movement. Hakman and Fletcher meet in a public place as Fletcher tries to persuade Hakman to turn over the implant of an EYE Tech executive as a means of exposing his dark deeds rumored to be recorded by the implant:

Fletcher: It’s unbelievable when you think about it. One in twenty of these people have an implant. How will that baby remember his mother years from now? Will he remember the special moments between them, or moments someone like you decides are special?

Hakman: My job is to help people remember what they want to remember, Fletcher.

Fletcher: Ah, that’s noble. But I don’t think you understand the scope of the damage. There is no way to measure the scope of the damage the Zoe implant has had on the way people relate to each other. Am I being filmed? Should I say this or not? What will they think in thirty years if I do this or that? And what about the simple right not to be photographed, the right not to pop up in somebody’s Rememory without even knowing you were being filmed?

Hakman: I didn’t invent the technology. If people didn’t want it they wouldn’t buy it, Fletcher. It fulfills a human need.

Fletcher: Alan, you take murders and make them saints! That’s why we need Charles Bannister. He was a public figure for EYE Tech, their star attorney, well respected, loved his family, gave to charity, and after you get through with him that’s all anyone will ever know. But Bannister is the first EYE Tech employee who’s implant has left the confines of the corporation. His widow fought for that. We know she’s hiding something about him and his daughter, and we’re gonna find it. EYE Tech’s hands are not clean. Bannister’s implant is evidence.

Hakman: So you want to destroy EYE Tech with a scandal.

Fletcher: Absolutely. The press would go ape shit. He’s the perfect candidate. I must have his footage.

[Moving slightly forward in the dialogue.]

Fletcher: These implants destroy personal history, and therefore all history. I will not stand by while the past is rewritten for the sake of pleasant Rememories. Tell me something: Why is your name the first on the list for cutting scumbags and low lifes?

Hakman: Because I forgive people long after they can be punished for their sins.

Fletcher: I know what you do. Why do you do it?

Hakman: Do you know what a sin eater is? It’s part of an ancient tradition. When someone would die they would call for a sin eater. Sin eaters were social outcasts, marginals. They would lay out the body, put bread and salt on the chest, coins upon the eyes. The sin eater would eat the bread and salt, take the coins as payment. By doing this the sin eater absorbed the sins of the deceased, cleansing their soul and allowing them safe passage into the afterlife. That was their job.

Fletcher: And what about the sin eater who bears the burden of all of those wrongs? Hmm?

Hakman: Are you worried about my soul, Fletcher?

As I’ve mentioned previously this film does not end well, and because of this it comes across as an average to bad film overall in that it holds up much promise but in the end it fails to deliver. Nevertheless, for those interested in moving beyond the need for a completely satisfying cinematic experience, it is worth watching and enjoying for those who would like to enter into science fiction’s ability to stimulate reflection on our own lives as we enter into stories involving our speculative future.

One Response to “The Final Cut: Sci-Fi Thriller Connects with Contemporary Issues”