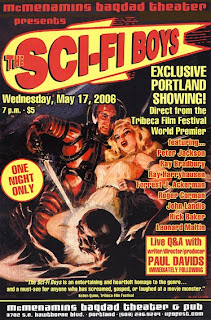

A while ago I was channel surfing and came across a late night showing of a great documentary film called The Sci-Fi Boys. I have commented on this film previously, which documents the tremendous influence of the films of Ray Harryhausen and the publishing work of Forrest J. Ackerman on several generations of young people. This film has won several awards, including the 2007 Hollywood Saturn Award for Best DVD from the Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Horror, and the 2007 fan-based Rondo Award for Best Independent Genre Film. The Sci-Fi Boys is the work of Paul Davids, who agreed to discuss the film and some of the interesting questions it raises.

A while ago I was channel surfing and came across a late night showing of a great documentary film called The Sci-Fi Boys. I have commented on this film previously, which documents the tremendous influence of the films of Ray Harryhausen and the publishing work of Forrest J. Ackerman on several generations of young people. This film has won several awards, including the 2007 Hollywood Saturn Award for Best DVD from the Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Horror, and the 2007 fan-based Rondo Award for Best Independent Genre Film. The Sci-Fi Boys is the work of Paul Davids, who agreed to discuss the film and some of the interesting questions it raises.

TheoFantastique: Paul, thank you for responding positively to my request for an interview. I caught a showing of your documentary, The Sci-Fi Boys on the SciFi Channel and enjoyed it immensely. I ended up purchasing a copy for my further review and reflection and I’d like to ask you some questions to tease out some of the thinking behind it. This documentary is obviously the result of your personal interests and passions on the subject matter. How did you develop these interests and what led you to produce this film?

Paul Davids: At specific moments in time, things burst upon the scene that capture the imagination of youth in a way that changes everything. Look at the advent of video games, from the first primitive Pong and Pacman and Space Invaders games, and how for awhile video games became an all-consuming entertainment and then got massively more sophisticated, eventually losing their novelty. You can name a hundred technological developments in our lifetime that had great impact like that. When I was a kid (pre cell-phone, pre-computer, pre-Internet, pre-video game) special effects in film were great novelty. It was like being fascinated with a magic trick. Gigantic monsters in movies and other effects would cause kids to wonder: how did they do that? And if you ever got over that question, the next question was can I do that too? And so the games began. There were no courses, textbooks, rules – it was (a) figure it out on your own or (b) find the magazine with an article that will give away the secrets. And there were few, because the techniques were largely guarded as “trade secrets.” Special effects were really special – even just the simple effect of making someone disappear or become gradually invisible…it all seemed so complex and ingenious. We had nothing that approached what can be done with high end graphics today that gives us moving imagery, sweeping us through heights and unusual angles to watch impossible things happening on screen. There is something similar or parallel in the personalities of those who embraced special effects and those who loved sleight of hand and other forms of magical illusions. I had those particular attractions. (I’ve been a member of the Magic Castle in Hollywood since the late 1980’s and try to go there once a week when I’m not traveling.) The “tricks” that are taken for granted in cinema today (and get a “ho hum” response now) were at one point in time impossible to accomplish and only vaguely imagined. Thus the pioneers of the field, men like Willis O’Brien, George Pal and Ray Harryhausen, were really brilliant inventors with soaring imaginations to take us as far as they did, each in their primes and their own time… they were master magicians of cinema who could fool the eye and trick us into imagining the impossible. Brilliant inventiveness keeps getting overtaken and supplanted, generation after generation. The generation of telegraph Morse Code could hardly conceive (except as science-fiction) the advent of the eras of telephone and television. The cycle continues.

TheoFantastique: The film focuses on the work and influence of Ray Harryhausen and Forrest J. Ackerman on several generations of young men that you call “the sci-fi boys.” How did you come to recognize the strong and ongoing influence of these men on professional filmmakers and average viewers alike?

Paul Davids: Their influence was impossible to ignore growing up in the late 1950’s and the 1960’s if you were a person who liked visual stimulation that was “out of the mainstream.” Whether you are talking about sci-fi imaginative imagery or sexual imagery or horror imagery, there was much less access and availability for any of that kind of sensory stimulation. If Forrest Ackerman caught your attention with his FAMOUS MONSTERS magazine, you got hooked. He always listed dozens of titles of upcoming monster or imaginative movies that were in the planning stages to be made. You waited and waited…. Half of them or more never were produced, or when they came out they had a different name and had changed so much you couldn’t recognize them from what he had described. But he teased and whetted your appetite and did something that great movie trailers do…created a sense of anticipation. If you became a Ray Harryhausen fan, you felt starved like a wanderer in the desert during a great drought in between the release of his films. You had to wait one or two years for the next one to come out! And there was hardly anything comparable to compete with him. There were a few imitators (anybody remember JACK THE GIANT KILLER?) but never would you think they were as good, as clever, as original. So like any forceful and inspiring personalities who dominate their professional field, these men became the Pied Pipers for males with intense imagination. They had vast followings. The kids whose lives were dominated by sports could have grown up and had very happy childhoods without ever hearing of them. But most of us horror/sci-fi fans lived for that Saturday afternoon double-feature, and we could only hope against hope that one of them would be a Ray Harryhausen film.

TheoFantastique: Those who might not consider themselves fantasy, sci fi, or horror fans and who enjoy films in these genres infrequently may not appreciate the impact of these men on the industry. Can you touch on some of their contributions to contemporary special effects as well as to the revitalization of the fantastic in films, and how they came to capture the imagination of numerous young people as filmgoers over the years?

Paul Davids: I think I’ve wrapped this answer into the preceding ones. But there was a small group of producers in the early days who believed totally in the power and importance of special effects. George Pal used to say that special effects were the “star” of any science-fiction motion picture. The impact of his influence, not just on entertainment, but on rallying a generation to the U.S. space program, was immense. George Pal made DESTINATION MOON, CONQUEST OF SPACE, WHEN WORLDS COLLIDE and WAR OF THE WORLDS…four major feature films dealing with different implications of man’s relationship to outer space, both exploration of space and outer space life. He was like a one-man NASA recruitment center. It’s worth noting though that the popularity of special effects ebbed and waned in cycles, like any other genre. When special effects were out of favor, George Pal couldn’t get any films to be greenlighted. It was the success of STAR WARS that really gave new life to special effects and to space films.

TheoFantastique: One of the things that struck me most as I watched your documentary was the strong connection I shared (and still share) with several generations of young boys from the 1950s through the 1970s who were captivated by the fantastic and the monstrous. The noted horror historian and author David J. Skal has expressed his feeling that these films and the monsters they portray function in some kind of function as participatory ritual for those who are a part of “Monster Culture”. He also feels that some expressions of the fantastic include “religio-mythic overtones”. Do you have any thoughts as to what was taking place in American culture during this timeframe that might have contributed to the hunger and thirst for the fantastic that helped make these men and their crafts so popular, and how they might have functioned beyond entertainment?

Paul Davids: The monster in movies, whether the gigantic beast or the slimy blood-sucking vampire, was the destroyer of civilization or the destroyer of souls. You’ve always had soul destroyers throughout the centuries, thus the concept of the Devil has been deeply ingrained. He deals with people on a one-to-one basis. But as for mass destruction, except for the plagues of the Middle Ages, the Baby Boom generation was the first to grow up with consciousness of the very real possibility of the total destruction of civilization as we know it. We were the first to grow up with the reality of nuclear weapons. So there was unconscious, suppressed fear and horror that was part of “normal” life. It was new to Western culture. In eastern culture, in Hinduism, the destroyer of worlds is built into the religious mythos. The triple godhead of the Hindus consists of Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva. Brahma creates the worlds. (And note that that’s plural — there are untold millions of worlds and Hinduism has always assumed that.) Vishnu preserves the worlds. But Shiva is the destroyer of worlds, and yet Shiva is worshipped and loved, not just feared. Hinduism, like Buddhism, recognizes the cyclical nature of life, that creation and destruction are the ultimate wheel, and that wheel turns round and endlessly, bringing worlds into existence and then shattering them. It’s a natural process. It’s God’s own original conception of creation. If not, why did God give stars a limited lifespan too and build into them the finality of exploding into a super-nova in their end? The Western concept of the Devil as an entity separate from God seems much more confining and limited. Western religions give a personality (in the form of the Devil or Satan) to the existence of evil – and at one level the monster is the cinema’s personification of evil. But the monster is not always like a demon — often the monster is simply the mindless force of absolute destruction and in that sense shows us different aspects and faces of Shiva, ultimate destroyer of worlds. In the West we should enlarge our dualistic concept of creation to something beyond just absolute good and absolute evil. The monster reminds us that we are stuck on that “wheel,” because although the monster destroys (thereby expressing our own inner primal rage and infantile fury) the monster is himself almost always destroyed too. The destroyer also has a destructive demise. Or at least he did before sequels came to rule the film business. Now many of those gigantic creatures simply must live to come again. (Anybody want to make a prediction about CLOVERFIELD?)

By the way, I must end with a plug for my new film, as long as we’re discussing religious mythology. Check out my website: http://www.jesus-in-india-the-movie.com/. This one will open your mind.

TheoFantastique: Paul, thanks again for participating in this interview, and for your fine documentary that helps preserve the legacy of those pioneers of the imagination that have been so influential.

One Response to “Paul Davids: Sci-Fi Boys and the Pied Pipers of the Imagination”