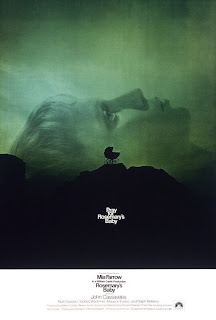

One of the horror films I remember watching in the 1970s as my television flickered with a Saturday night’s ritual connected to my local Creature Features was Rosemary’s Baby (1968). Next month this film will see its 40th anniversary, and I thought I’d use the occasion to take a walk down memory lane with this piece of classic horror cinema.

One of the horror films I remember watching in the 1970s as my television flickered with a Saturday night’s ritual connected to my local Creature Features was Rosemary’s Baby (1968). Next month this film will see its 40th anniversary, and I thought I’d use the occasion to take a walk down memory lane with this piece of classic horror cinema.

As Nikolas Schreck recounts the origins of the film in his interesting book The Satanic Screen (Creation Books, 2000), William Castle, known for his creativity and showmanship with horror films like The Tingler (1959) and House on Haunted Hill (1959), purchased the film rights to Ira Levin’s novel Rosemary’s Baby from 1967. Castle had the good sense to try to make the most of a film adaptation of the story and he did so by hiring Roman Polanski as director. Previously Polanski had directed other horror films such as Repulsion (1965) and Dance of the Vampires (1967). With Rosemary’s Baby he would prove himself to be a gifted director, and this film would remain his horror masterpiece perhaps surpassed byl his work with The Ninth Gate (1999).

Polanski’s treatment of his subject matter, the struggles of a young urban housewife to come to term with a pregnancy of questionable origins, draws upon treatments of the feminine and the body that find their origins in Gothic fiction, but Polanski developed and updated these aspects to reflect elements of the Sixties counterculture. For these reasons the story “hit home” for viewers that helped place supernatural horror in the middle of American suburbia. As Virginia Wright Wexman discusses in a chapter in American Horrors: Essays on the Modern American Horror Film, Gregory A. Waller, ed., (University of Illinois Press, 1987), the story moves the location for the tale from the exotic and distant places of the horror films of the 1930s and 1940s and places it squarely in a modern urban environment. Polanski also deals different with the object of horror, shifting from a typical concern for projecting horror as the external other to portraying protagonists in ways that cause the audience to identify with the character and their own inner struggles with objects of horror. Wexman suggests that earlier horror films were “marked by a sense of dissatisfaction between self and body,” and this is explored and modified by Polanski as he explores aspects of body and sexual dis-ease.

Wexman notes that the film also explores the religious element in ways that reflected the social turmoil of the times. This is expressed in the dramatically different way in which Polanski’s film presents the supernatural. The Levin story drew stark contrasts in its traditional, unambiguous presentations of good versus evil, God and the devil. Not so in Polanski’s treatment where ambiguity thrives, and where traditional religion in the form of Christianity is satirized and turned on its head. As Wexman notes, “Polanski calls all belief into question by continually playing tricks with the film’s illusion of reality.”

The film would go on to be very well received only as a generally good cinematic effort with its ability to provide great frights for viewing audiences, but also because touched on a number of elements that were of great interest in the culture of the time, including stories of Satanism, stereotypical representations of a satanic coven, secret societies and “cults,” questions surrounding the body and sexuality, and issues surrounding traditional authority structures. The film was influential as well in that it spawned responses in the form of imitators such as The Curse of the Crimson Altar (1968), and influenced later films such as The Exorcist (1973) and The Omen (1976). As Rosemary’s Baby celebrates its 40th birthday I wish it many more years as a source of scares and critical reflection.

There are no responses yet