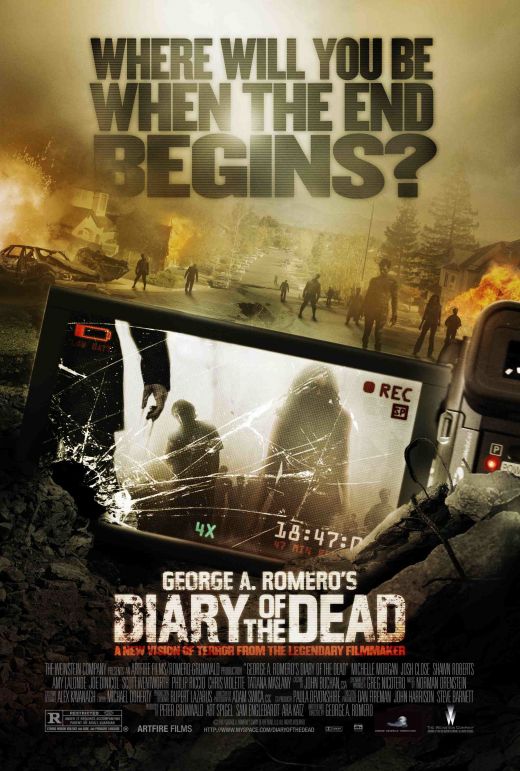

Last weekend my teenage son bought me a copy of Diary of the Dead (2008), George Romero’s latest installment in his infamous zombie series of films. I realize that the movie has been out for a while and that a number of reviews and commentary have been posted, but given the focus of this blog I may have something to contribute as I touch on aspects of Romero’s continuing social and cultural critique 40 years after his groundbreaking classic Night of the Living Dead (1968).

While I cannot say that this is my favorite Romero zombie film it did not disappoint, and it rounds out the director’s treatment of this iconic monster. In the late 1960s Romero changed horror films and popular culture forever with his unique take on zombies, transforming the previous conceptions of the figure of a living being in drug-induced limbo in servitude to others taken from from voodoo to corpses risen from the dead in search of the flesh of the living. The original film introduced Romero’s frightening apocalyptic scenario and each successive film in his series built upon this as the living came to grips with the challenges of survival. Diary of the Dead brings Romero’s zombie films full circle in that they return the time frame to the initial moments after the dead begin to rise.

A unique aspect of this film is its almost exclusive use of hand held cameras which simulate the characters’ subjective viewpoints as they record the zombie onslaught. Of course, this technique goes back to The Blair Witch Project, but this is the first time it has been applied to zombie horror. At times I found the use of this technique forced at times and I wondered whether the human desire for video documentation of graphic tragedies could really be stretched to such extensive proportions. Even so, I appreciated what Romero was trying to accomplish with his use of visual imagery in this fashion. As Romero fans are aware, the director has incorporated social and cultural critique in his zombie films, focusing in the past on racism, the breakdown of the nuclear family, and consumerism. Diary continues in this tradition by offering a brief critique of racism and an extended critique of our media saturated and voyeuristic culture.

Four decades after his initial critique of race in America, Diary expresses Romero’s continued concerns in this area. It is expressed in the film as the group of college filmmaking students traveling to escape the zombies encounter a group of African Americans. With the collapse of society they have formed a tight knit group focused on race as they come together to build their collection of weapons, gas, and food for survival. Although this is a brief segment of the film and nowhere near the extended treatment provided in Night of the Living Dead, at one point the leader of the African American group states that the tragedy has provided his group with the means of attaining power. This is obviously indicative of Romero’s continued concerns about racism in America, but given that this film was released prior to Barrack Obama being elected to the presidency it would be interesting to see how this segment of the film might have been modified with this change of circumstances reflecting changing American attitudes toward race.

Diary also includes a major and sustained critique of America’s obsession with the media and voyeurism through the recorded visual image. This plays itself out from the opening scene where the group of college filmmaking students stops their horror film production and the director continues filming which sets the stage for his continued recording of virtually every moment of their struggle for survival. This makes many of the other students uncomfortable, but eventually they take it for granted, and one of them even takes up the cause for continued documentation with [spoiler alert] the eventual death of the character behind the camera. Beyond the critique of our propensity to want to record and share every aspect of our lives, Romero also offers a critique of the expansive presence of the media and its technologies. Various images are shown in the film with voice-over narration that portray our global news media reacting to the zombie tragedy hauntingly familiar from 24/7 news broadcasts available via cable and satellite. Further, the characters in the film depend greatly upon their technology in the form of cell phones and wireless Internet connections expressing great surprise and dismay when these technologies give out as a result of the breakdown in society. No doubt Romero takes advantage of the media and its related technologies that have benefited him in the production and dissemination of his films, but he raises valid concerns about the extent of influence of these things and our obsession with them in terms of priorities and dependencies.

One might wonder whether Romero has gotten any less pessimistic since he first captured his zombies on celluloid. In his first zombie film a strong sense of pessimism, if not nihilism, is present as the major character survives the zombies and great interpersonal conflict with the living only to end up dead as a result of an overzealous “redneck” zombie hunting squad. This pessimism continues throughout the remainder of Romero’s zombie films with a slight injection of hope in Land of the Dead as it appears that zombie culture and living human culture might be able to learn to co-exist. With what may be Romero’s final installment in his zombie series, Diary seems to return once again to a sense of pessimism regarding human nature and the possibilities of avoiding self-destruction. It does so through not only the scenes of worldwide chaos that ensue with the breakdown of society, but most strongly in the final scene. This involves a dangling zombie tied by her hair to a tree limb. Once again the symbol of unthinking human destruction surfaces in the form of the “rednecks” who have been using zombies for target practice. In the case of the woman hanging from the tree they use a shotgun and shoot her in the head leaving only the head from the nose up remaining on the tree, the rest of her body falling limp to the ground. The camera slowly zooms in to the remains of the head as a blood trickle slowly works its way down from the tear duct of the left eye as the narrator asks the question as to whether humanity is worth saving. Although this scene is very graphic it is also very effective in providing a strong visual that climaxes the film while drawing attention to the human predicament. Like The Mist, this film suggests that it is only our social structures that prevent us from self-destruction, and we might indeed engage in sober self-reflection on our violent tendencies. It appears that Romero may not think humanity is worth saving, particularly if we are little more than self-obsessed, animated meat bent on annihilating ourselves and others, whether we document this in our visual diaries or not.

George Romero zombie film fans, and those interested in the social critique which is provided through late modernity’s favorite monstrous icon, will find this film entertaining and thought provoking.

I thought this one was actually very good.

I watched this film (yes, I said film. It has rated that high standard.) last night. I felt that Romero truly has out done himself. I scares the heck out of me how he hits the nail on the head with his critiques on today’s society. I was both angry and enthralled by the main character’s desire to capture these events from behind his camera with little or no regard for his friends, let alone his girlfriend. Zombies. They do not scare me. Humans…now there is a creature to fear. I did not, however, care for the redneck comment. I have found city dwellers to be as sadistic in their lust for violence. And not ALL southerners are racist.

If you enjoy this movie, then I recommend you read “the walking dead” and how one man is trying to deal with a changing world where the social norms are thrown out the window all in the name of survival.