A while ago I first encountered Matt Cardin when he nominated this blog for an award between bloggers. Matt pursues his blogging at The Teeming Brain. In addition to being flattered, it was good to learn of someone else thinking through the issues related to the connection of horror and religion.

A while ago I first encountered Matt Cardin when he nominated this blog for an award between bloggers. Matt pursues his blogging at The Teeming Brain. In addition to being flattered, it was good to learn of someone else thinking through the issues related to the connection of horror and religion.

Matt’s biography on his website provides us with some background on his work:

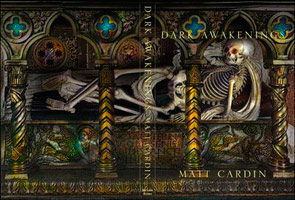

Matt Cardin is the author of Dark Awakenings (forthcoming), a collection of stories and academic essays exploring the intersections between religion and horror. His first book, Divinations of the Deep (2002), was chosen by Ash-Tree Press to launch their New Century Macabre line of contemporary literary horror fiction. His stories, essays, reviews, and interviews have appeared in Icons of Horror and the Supernatural, The HWA Presents: Dark Arts, Alone on the Darkside, The Thomas Ligotti Reader, Cemetery Dance, The New York Review of Science Fiction, Lovecraft Annual, and elsewhere.

He is a regular contributor to the horror review journal Dead Reckonings, and will contribute several entries, including an examination of vampires and religion, to the forthcoming reference work Encyclopedia of the Vampire: The Living Dead in Myth, Legend, and Popular Culture, edited by S.T. Joshi.

I was privileged to be able to take a look at Dark Awakenings, and as a result the following interview came together.

TheoFantastique: Matt, thanks for making me aware of your blog, and of your work in academic reflection on horror. It’s nice to find someone exploring a similar pathway in regards to horror. I’d like to begin by finding out a little about your background and passion for this subject matter. How did you come to be interested in horror, and what background do you bring to its analysis?

Matt Cardin: I tended to be interested in dark and scary entertainments from the time I was a child, despite – or maybe because of – the fact that they truly terrified me. I’m talking about real fear, to the point of mild neurosis. One time when my parents were away, I watched Kingdom of the Spiders – yes, the William Shatner cheese-fest – on network television and literally couldn’t sleep for a couple of days afterward. I had some similar experiences with Creepshow, The Twilight Zone, and a couple of episodes of Tales from the Darkside. There were comic books and novels, too. You get the idea. These things both terrified and horrified me, although I didn’t make that distinction until much later. I also took my inherited religion of evangelical Protestantism with the utmost seriousness, engaging in regular Bible reading, prayer, and so on. Somehow these tendencies started playing off each other in philosophical and emotional ways, and when I discovered Lovecraft in my early teens at about the same time that I began discovering non-Christian religious books and ideas, as well as philosophy in general, things just sort of came together to form me as a person who is deeply fascinated with the experience and theory of horror, particularly of the spiritual and philosophical sort. It also didn’t hurt that I began to experience life authentically and existentially as a kind of nightmare for a period of years in my 20s when I suffered from horrific episodes of sleep paralysis and the attendant hypnagogic visions.

So that’s the personal background that I bring to horror analytics. Academically, I studied film theory and video production as a college undergraduate, and I minored in philosophy. I spent quite a few years earning a master’s degree in religious studies, and my professors at Missouri State University were very good to let me pursue my multi-sided interests in horror and religion, and religion and film, and religion in horror, and horrific religion, and so on.

TheoFantastique: How did your book Dark Awakenings come together?

Matt Cardin: Dark Awakenings came about as a means of collecting my uncollected work, the stuff that hadn’t been collected in, or that had been written after, the publication of my first book, Divinations of the Deep. In the mid-1990s I began writing horror fiction out of that aforementioned experience of nightmare-fueled existential horror. Divinations was one result. The material in Dark Awakenings is another. The book was in the works for several years with its publisher, Mythos Books, and it began as a fiction-only collection. About three years ago I was commissioned to write a long entry about the iconic figures of the angel and the demon in horror literature and film for a reference work titled Icons of Horror and the Supernatural: An Encyclopedia of Our Worst Nightmares. I ended up producing an essay that ran nearly 10,000 words over the already generous word limit. This of course necessitated some serious paring down, and I approached Mythos to ask whether they’d be interested in publishing the full version as a standalone monograph. David Wynn, the proprietor and editor, suggested adding it along with some of my other academic nonfiction to Dark Awakenings. So that’s what we did, and thus was born a strange hybrid book that I’ve taken to describing as “horror fiction and nonfiction,” which tends to draw requests for an explanation, as when I listed that description in my bio for the programming brochure at a literary convention in Austin last summer and ended up having to explain my meaning to audience members at all the panels I spoke on.

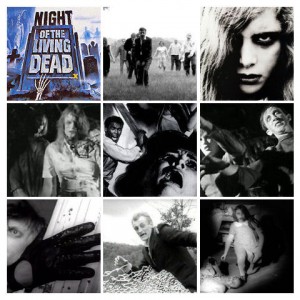

TheoFantastique: One of your chapters in the book was of great interest to me. It was “Loathsome Objects: George Romero’s Living Dead Films as Contemplative Tools.” In this chapter, among other things, you discuss the spiritual aspects of the first three installments in Romero’s zombie films. Most commentators either ignore this element, or look at them as expressing little more than nihilism. How did you come to focus on this aspect of the films?

TheoFantastique: One of your chapters in the book was of great interest to me. It was “Loathsome Objects: George Romero’s Living Dead Films as Contemplative Tools.” In this chapter, among other things, you discuss the spiritual aspects of the first three installments in Romero’s zombie films. Most commentators either ignore this element, or look at them as expressing little more than nihilism. How did you come to focus on this aspect of the films?

Matt Cardin: Before I say anything about “Loathsome Objects,” I should point out that the question of the spiritual element in those films has now received a masterful book-length explication by our mutual friend Kim Paffenroth, the religion scholar and zombie novelist who wrote Gospel of the Living Dead: George Romero’s Visions of Hell on Earth. I wrote my piece three years before Kim’s book appeared, and surely would have used him as a major resource if the timing had been different.

That said, my fundamental trajectory in considering the spiritual aspect of Romero’s films is quite different from Kim’s. He read them for their Judeo-Christian moral meanings, and drew lots of fascinating parallels between their iconography and that of Dante’s Inferno. I took a more explicitly reader-oriented approach by focusing on the way the films might be used as objects of and/or tools for spiritual contemplation through a deliberate focus on their muted spirituality and overt gore. My general approach came from two papers that I had written some years earlier. In one of them, I explored the possibility that the nasty, gory, morally repugnant story in chapter 19 of the biblical Book of Judges, where a Levite lets a gang of men rape his concubine to save his own skin, and then ritually dismembers her and sends the pieces to all the tribes of Israel, might actually be able to jar the reader into an experience of ego transcendence with its combination of moral horror and body horror. In the other, titled Awakening from the Nightmare: The Horror Film as a Tool for Transcendence, I applied the same idea to modern horror films in general, dating the “modern” period in standard fashion from 1968 and Night of the Living Dead. I’ve been veritably mesmerized by the Living Dead films for years. I remember watching and rewatching them obsessively on VHS in high school, and then really watching and rewatching them as an undergraduate college student. And the guiding idea from those previous papers just blossomed eventually to encompass them.

The specific stimulus for writing the paper came when I took a graduate seminar devoted entirely to the subject of religion and food, which many people might not know is a thriving field of inquiry. I justified writing the paper for that particular class by devoting a large portion of it to a consideration of cannibalism and its symbolic meanings. It was an unconventional choice, I think, but the professor, Martha Finch, was great about it. She offered a lot of encouragement and advice. A couple of years later I expanded and revised the paper to serve as one of my final research projects for the M.A.

TheoFantastique: Let’s talk about a few of the elements of your discussion on these matters if we could. As you begin developing your assessment you discuss abjection in regards to the horror film in general, and in Romero’s zombie films in particular. Can you summarize some of your thinking here?

TheoFantastique: Let’s talk about a few of the elements of your discussion on these matters if we could. As you begin developing your assessment you discuss abjection in regards to the horror film in general, and in Romero’s zombie films in particular. Can you summarize some of your thinking here?

Matt Cardin: The theory of abjection basically offers a psychologically oriented explanation of the way the perceived boundary between self and other, ego and not ego, I and “not-I,” plays out in culture, society, art, and the individual psyche. A lot of it revolves around the subjective sense of the body and the universal tendency of people and cultures to view bodily detritus – excretions, clippings, amputated limbs, and so on – as revolting and unacceptable. Such things are collectively termed “the abject” in this theory. Are they self or other? It’s hard to say, since they originate in and from the body but then confront us as objective, dehumanized presences, which call into question our narcissistic self-images. “The abject” refers to the rejected parts of our identities that fill us with a veritably uncanny sense of loathing.

The ultimate object of abjection, as explained by Julia Kristeva, the European scholar who developed the theory in her seminal 1982 book The Powers of Horror, is the human corpse. Corpse horror in various forms is a recognized cultural reality around the world, and the theory of abjection would say this is because a corpse confronts us with the definitive instance of “not-I” in the form of an object that was formerly human but is now an alien shell of rotting matter that has been emptied of what we think defines us, but whose shape reminds us that it once was us. What was human has become not-human, and this calls into question not only our own future fate but the nature of our current sense of identity.

The corpse connection and the general focus on bodily goo provides the link between the theory of abjection and horror film studies, where quite a few scholars and critics have invoked Kristeva and her work. In my paper I quote one film scholar who characterizes the modern horror film in all its gory glory of steaming viscera and severed body parts as a series of endless iterations of “the fantasy of abjection,” that is, as the outworking of a kind of collective compulsion neurosis in which movie audiences crave confrontations with scenes that arouse the horror of abjection, which is in essence a primal type of horror that’s hardwired into our psyches.

Over my years of reading religion and philosophy and becoming increasingly interested in the question of transcending or awakening from egoic identity, while at the same time pursuing a kind of connoisseur-ship of horror entertainment and finding myself drawn increasingly to an engagement with insanely gory horror films, I starting noticing interesting interconnections between the issue of spiritual awakening, defined as a subjective awakening to the provisional and limited nature of egoic consciousness, and the modern horror film with its perpetual playing on the question of human identity through all of those endless invocations of abjection. Given that Romero launched this era in film history with NOTLD, a movie that not only broke new ground in gore but created a whole new monster in the form of the zombie as a reanimated corpse – a monster that confronts viewers with the literal embodiment of that age-old apotheosis of abject horror – it seemed to me there were grounds for a fruitful study of his zombie films in this regard.

TheoFantastique: I was especially interested in your discussion of the significance of the act of eating as a significant personal and cultural ritual, and how Romero’s depiction of cannibalism in connection with zombies subverts this. How is this done, and what does this symbolize in Romero’s films?

TheoFantastique: I was especially interested in your discussion of the significance of the act of eating as a significant personal and cultural ritual, and how Romero’s depiction of cannibalism in connection with zombies subverts this. How is this done, and what does this symbolize in Romero’s films?

Matt Cardin: The field of food theory points out that the act of eating is laden with cultural meanings. In essence, the entire pattern of a civilization or society, including its fundamental assumptions about human roles and identities, can be found encoded in the customs and rituals surrounding the preparation and eating of food. Not insignificantly, food itself has a kind of uncanniness that again invokes abjection in an oblique way, since food is an external something that you take into yourself, a “not-I” that becomes part of yourself, thus highlighting that liminal zone between self and other again.

Thinking in these terms, what’s the meaning of an act like cannibalism? The act of one human eating another signifies a shredding of the boundary between self and not-self, the literal ingestion of one self by another, which represents the most profound possible violation in a civilization like, oh, say, the modern Western one, where the concept and felt experience of autonomous individuality and interiority are not only axiomatic but sacred. Cannibalism also signifies the collapse of civilizational norms, since all advanced civilizations frame it as one of the vilest forbidden acts. If food is as culturally central and symbolically potent as food theory asserts, then cannibalism represents an Armageddon-like overturning of pretty much everything.

In the Living Dead films, you also have the added philosophical juiciness of the fact that the cannibals are those aforementioned embodiments of corpse horror. Those films are like the perfect package for symbolizing absolute horror on every imaginable level. Dead people returning to life and eating the living? The very idea is categorically blasphemous, even in the secular modern West.

TheoFantastique: When you move to your discussion of the “spiritual angle” of The Night of the Living Dead series, you pick up on a line in Dawn of the Dead. Can you discuss this line in a reading from a Judeo-Christian framework, and if true what this would say about God in the context of the zombie apocalypse?

Matt Cardin: The line in question is actor Ken Foree’s classic, “When there’s no more room in hell, the dead will walk the earth.” In my paper I consider this in tandem with the longer apocalyptic speech given by the character of John in Day of the Dead, and interpret both against the backdrop of the films’ definitive framing of all conventional forms of social authority, including the religious type – not to mention the military, media, masculine, and scientific types – as empty and ineffective. In that void, the religious pronouncements from Dawn‘s Peter and Day‘s John – note the overtly biblical and apocalyptic names –frame God as a kind of wrathful demiurge who, for unknowable reasons, has either deliberately launched or passively allowed a bloody, horrific apocalypse to play out on planet earth. To say “There’s no more room in hell” implies that God has filled hell to capacity with damned souls, and has now casually designated earth as the space to catch the overflow. Earth has effectively become hell’s annex by default. In Day John offers various speculations about the origin and meaning of the zombie plague, all centering on the idea that it’s God’s doing, and then concludes that “You ain’t never gonna figure it out, just like they never figured out why the stars are where they’re at.” In other words, the plague is just happening, it’s just something that God is allowing or doing, and we simply have to endure it. The uselessness of traditional authority reaches all the way up the ladder of rank and being to heaven itself.

Matt Cardin: The line in question is actor Ken Foree’s classic, “When there’s no more room in hell, the dead will walk the earth.” In my paper I consider this in tandem with the longer apocalyptic speech given by the character of John in Day of the Dead, and interpret both against the backdrop of the films’ definitive framing of all conventional forms of social authority, including the religious type – not to mention the military, media, masculine, and scientific types – as empty and ineffective. In that void, the religious pronouncements from Dawn‘s Peter and Day‘s John – note the overtly biblical and apocalyptic names –frame God as a kind of wrathful demiurge who, for unknowable reasons, has either deliberately launched or passively allowed a bloody, horrific apocalypse to play out on planet earth. To say “There’s no more room in hell” implies that God has filled hell to capacity with damned souls, and has now casually designated earth as the space to catch the overflow. Earth has effectively become hell’s annex by default. In Day John offers various speculations about the origin and meaning of the zombie plague, all centering on the idea that it’s God’s doing, and then concludes that “You ain’t never gonna figure it out, just like they never figured out why the stars are where they’re at.” In other words, the plague is just happening, it’s just something that God is allowing or doing, and we simply have to endure it. The uselessness of traditional authority reaches all the way up the ladder of rank and being to heaven itself.

TheoFantastique: So what do you see as the thrust of the spiritual message of the films?

Matt Cardin: It seems like a message of utter nihilism to me, a kind of “Gnostic nightmare,” as it were. That’s not to say the films hold out the possibility of a secret gnosis or mystical knowledge, but that they posit a spiritual reality from which embodied life is cut off. The second-century Gnostics viewed the life of the body as a horrific thing, something to be loathed and transcended. One well-known Gnostic motif was the identification of physical life here on earth as hell itself, the lowest possible point in a multilayered cosmos. I think it’s possible to read Romero’s Living Dead films as depictions of a quasi-Gnostic scenario combined with a “no exit” motif, a world that has suddenly and inexplicably morphed into hell, where a person’s delicate inner experience, his or her interiority, subjecthood, self, “soul,” has no ultimate metaphysical ground and faces the constant danger of being violated and consumed by the ultimate nightmare. It’s damnation without the possibility of salvation, with a distant God presiding impassively over it all.

TheoFantastique: But you move beyond this to discuss the inadequacy of a theistic reading of the spirituality of the film. Why do you see this as necessary within the narrative framework of the films, and for theological reasons as well?

Matt Cardin: I’m keen on the idea that there are no definitive, one-size-fits-all readings of creative works, and so I offer the above reading simply as one example of a valid exegesis, a valid reading of the Living Dead films that takes its cues directly from what they present. And I think perhaps it’s a reading that contains within itself the seeds of another view, in the form of the questions it begs. Why is God even necessary in such a reading? What’s the point of a divine punishment that contains no redemptive purpose? Isn’t Romero’s zombie plague just as amenable to a “natural disaster” type of interpretation, with the zombies functionally equivalent to, say, the cataclysmic natural events of a movie like 2012? The very “no exit” nature of the Gnostic/nihilistic reading makes such speculations worthwhile.

But the spiritual angle on the films is so very potent and fruitful that it’s a shame to abandon it, so another reading that retains this aspect but reframes it in nontheistic terms seems viable.

TheoFantastique: What do you suggest as an alternative religious reading for the spirituality of the films?

Matt Cardin: I suggest a reading that departs from exegesis proper and posits a more directly active role for the reader. What came to me as I considered these films, and also as I considered the biblical Book of Judges and the modern horror film in general, as described earlier, was the idea that a person might be able to use them as objects of spiritual contemplation in a way that echoes certain meditative and contemplative practices generally associated with Eastern philosophical and spiritual traditions. Although it is of course a gross simplification even to think in terms of “Eastern religion” and “Western religion,” there are indeed recognizable tropes and broad lines of family resemblance that characterize world religious traditions and spiritual practices across an East/West divide. And on the Eastern side there’s a more prevalent tendency to face negative emotional and psychological states with openness, to embrace them and see one’s way through them, as opposed to the dominant Western tendency of regarding them as illegitimate or even sinful.

Matt Cardin: I suggest a reading that departs from exegesis proper and posits a more directly active role for the reader. What came to me as I considered these films, and also as I considered the biblical Book of Judges and the modern horror film in general, as described earlier, was the idea that a person might be able to use them as objects of spiritual contemplation in a way that echoes certain meditative and contemplative practices generally associated with Eastern philosophical and spiritual traditions. Although it is of course a gross simplification even to think in terms of “Eastern religion” and “Western religion,” there are indeed recognizable tropes and broad lines of family resemblance that characterize world religious traditions and spiritual practices across an East/West divide. And on the Eastern side there’s a more prevalent tendency to face negative emotional and psychological states with openness, to embrace them and see one’s way through them, as opposed to the dominant Western tendency of regarding them as illegitimate or even sinful.

So, what if one abandoned the theistic reading of the Living Dead films but retained the hopelessness, nastiness, and gore, the idea of that vortex of flesh in which the human self doesn’t have any ultimate foothold or validity, and then one positively embraced that? Anybody who knows anything about Buddhism might begin to hear echoes of the idea of samsara, the world of suffering that is phenomenal reality, and of the insight that there’s actually no such thing as a stable self in all this, but only layers of inculcated physical, psychological, and social tendencies that cluster around a core of emptiness, the awakening to which constitutes liberation or enlightenment. Making this leap, one might also note that there has been in Buddhism a historic practice of focusing contemplatively on the transience and impermanence of the physical body as a means of deepening one’s experiential insight of these things. There are even accounts of an age-old practice of meditating on corpses in various states of decay, in order to really drive home the point that this flesh-mobile we’re all driving isn’t actually us. The body is characterized by organic processes that are widely considered by polite society everywhere to be rather disgusting. And that’s when it’s operating normally and healthily! Beyond this, the body will inevitably suffer injury and decline. It will die. It will rot. It will go away. What will be left then? The whole point of such exercises, even the merely mental ones, let alone actual corpse meditations, is to awaken a person to the observing presence that is his or her higher/wider/deeper self – pick your metaphor – beyond the little knot of ego consciousness that forms the extent of what most of us know. When the body’s destruction and dissolution are fully recognized, accepted, experienced, then what? What remains? Answer: pure awareness, “Buddha nature,” noumenal reality. Of course this is all based on the axiomatic assumption that consciousness is not just an epiphenomenon of material processes, which I think is quite defensible, but which is an issue that lies outside the scope of my argument here.

If you’ll forgive me the laziness of quoting myself from my own work: “To view these films in this way, as tools for aiding in this contemplation of physical and psychological mortality, is to experience them exactly as we have described them in this paper, with all their hopelessness, with all their gore and violence, all the horror of abjection attendant upon the sight of animated corpses, still active with full, emotionally penetrating effect, and yet to experience a veritably alchemical transmutation of the horror and hopelessness into something else, something that may approach a genuine epiphany about the nature and identity of one’s true self.”

Maybe a faux corpse meditation of this sort represents a decidedly dark way of getting at these matters. But it still strikes me as an interesting and, maybe, a valid one.

And please note that I offer the whole thing half seriously and half as an elaborate and self-conscious exercise in quasi-fiction making. That’s why I grouped the short stories and the novella that make up the first half of Dark Awakenings under the section heading “Fictions,” and the academic exploration that make up the second half under the heading “Other Fictions.” When I read the Living Dead films as possible tools for a kind of Buddhistic spiritual contemplation, or the Book of Isaiah as a quasi-Lovecraftian horror story, I’m not sure where my fiction making and my scholarly explication pick up and leave off.

TheoFantastique: Matt, thanks again for your explorations and for some stimulating reading.

Matt Cardin: You’re welcome. And thank you in turn for TheoFantastique. I really enjoy what you do here.

4 Responses to “Matt Cardin: Spirituality in Romero’s Living Dead Films”