Regular readers of TheoFantastique might recall my previous interview with my friend Matt Cardin of The Teeming Brain blog, and author of Divinations of the Deep (2002) and Dark Awakenings (2010). Matt and I follow similar pathways in our explorations of horror and religious studies, and in this interview Matt shares his thoughts on the connections between horror literature and the biblical book of Isaiah, a topic he explored in a part of Dark Awakenings.

Regular readers of TheoFantastique might recall my previous interview with my friend Matt Cardin of The Teeming Brain blog, and author of Divinations of the Deep (2002) and Dark Awakenings (2010). Matt and I follow similar pathways in our explorations of horror and religious studies, and in this interview Matt shares his thoughts on the connections between horror literature and the biblical book of Isaiah, a topic he explored in a part of Dark Awakenings.

TheoFantastique: Matt, thanks for coming back for a further discussion. Another element of your book that intrigued me was your essay “Gods and Monsters, Worms, and Fire: A Horrific Reading of Isaiah.” Your reading will likely alarm any conservative Protestants in particular who come across this interview, but how did you come to think of the biblical book of Isaiah, particularly chapters 24, 34, and 66 in terms of a horror story?

Matt Cardin: It was the result of a collision between my literary and philosophical passions and the work I did in grad school. The beginning of my career as a horror writer overlapped with the time I spent in the religious studies M.A. program at Missouri State in the late 90s and early 2000s. My professors proved quite accommodating as I lobbied to incorporate my passion for philosophical horror into my religious scholarly studies. In 2002 I took a semester-long seminar class devoted entirely to the study of Isaiah. This was four years after I had written “An Abhorrence to All Flesh,” a story that ended up appearing in my first fiction collection, Divinations of the Deep. The book came out the very month that I started taking the Isaiah class. The title “An Abhorrence to All Flesh” came from Isaiah’s final verse. I had latched onto in a moment of inspiration that I really didn’t consciously understand. Then, in the early weeks of that seminar class, with my book just published, I began to realize there was more to say along the same lines, only in nonfiction form. It was truly a daimonic prompting, all intense and passionate. It was like, “Oh, so this is what I was unconsciously noticing in Isaiah a few years ago.” At some point I rediscovered a paper by literary scholar Roger Schlobin that I had read a few years earlier: “Prototypic Horror: The Genre of the Book of Job.” Schlobin is an English prof at Purdue who has focused a lot on the literature of the fantastic, and in that paper he developed a three-part test or schema for determining whether a given text should be classified as horror. Then he applied it to Job and found that the answer was definitely yes. Bells and buzzers went off in my head, and I knew I had my semester’s project in hand. The paper took on a life of its own and became one of those really satisfying projects where everything comes together and synchronicitous events explode all around as exactly the right materials come effortlessly to hand. A couple of years later I revised and expanded it to serve as one of my terminal projects for the M.A.

TheoFantastique: Many Protestant evangelicals draw upon a historical-critical method in approaching the biblical text, and while you acknowledge these you also state that you draw upon an “explicitly reader-oriented” approach. Can you touch on this and how it impacts your reading of Isaiah?

Matt Cardin: What moves me in the Bible — in any religious text — is mythic meanings. I mean this in the high sense, the “myth is truer than literal truth” sense. And one way to access and work with this is through a reader-oriented approach that focuses on how you’re interacting cognitively and emotionally with the text at the moment. Reader-response criticism is an accepted and respected critical methodology, and I combined it with a literary-esque approach to understand how and why the Isaian text was hinting to me that it could be validly read as a cosmic horror story of a quasi-Lovecraftian sort. My goal ended up being to see if I really could offer a reading that remained true to the text and yet elicited a meaning from it that radically inverted just about everything I had ever been told about it, and that explained to me why I was feeling the same fascination toward it that drew me to Lovecraft and cosmic horror.

TheoFantastique: As you develop your thesis you apply Roger Schlobin’s “three, critical elements of horror” to Isaiah. Can you describe these for us?

Matt Cardin: Schlobin says horror stories do three things. First, they “distort cosmology” by reducing the normal world to chaos. In every horror story you’ve ever read or seen, something comes up — monster? killer? super plague? — to upset the established social/moral/personal cosmos, which of course creates the story’s major dramatic tension by making the reader long for that order to be restored.

Matt Cardin: Schlobin says horror stories do three things. First, they “distort cosmology” by reducing the normal world to chaos. In every horror story you’ve ever read or seen, something comes up — monster? killer? super plague? — to upset the established social/moral/personal cosmos, which of course creates the story’s major dramatic tension by making the reader long for that order to be restored.

Second, horror stories invert “signs, symbols, processes, and expectations.” That is, they horrify by creating a situation — the distorted cosmology of the first point — where conventional meanings and attitudes are reversed, and things that would have formerly seemed repugnant and awful now seem desirable. Think of the brutal violence the hapless heroine of a slasher movie inflicts on the killer. (This is my example, not Schlobin’s.) Think of Laurie in Halloween. She’s all sweet and virginal and gentle, and then she has to stab Michael with a knitting needle in the neck and a coat hanger in the eye, and we’re cheering her, for God’s sake. The kind of violence the monster himself represents has been flipped and made desirable. It’s like the monster’s desires are winning by default.

Third, horror stories portray a monster-victim relationship in which the human will, human autonomy, is utterly devastated. And, crucially, the monster is somehow incomprehensible. It’s thoroughly a-cosmic. In other words, its true nature and motivations are so thoroughly at odds with the normal human situation that we simply can’t comprehend it within our available frame of reference. Again, think of Michael Myers as “The Boogeyman,” the embodiment of raw, pulsing, incomprehensible, unkillable murderousness.

The true test of any kind of explanatory system like Schlobin’s is, of course, whether it actually works in action when you apply it to different texts. I’ve tried it idly with dozens of horror stories, novels, and movies. And it works.

TheoFantastique: How does Isaiah exhibit these elements in your view?

Matt Cardin: There’s a specific point-by-point answer and a more general answer that informs the other one with the correct intellectual-emotional undercurrent.

The general answer has to do with the recurring hints all throughout the Hebrew scriptures that Yahweh, the Hebrew god, is infinitely powerful, unpredictable, and somehow deeply terrifying or horrifying. Rudolf Otto did a really marvelous job of conveying this in his classic The Idea of the Holy when he said Yahweh’s wrath is baffling and terrifying, since it’s “like a hidden force of nature, like stored-up electricity, discharging itself upon anyone who comes too near. It is incalculable and arbitrary.”

The specific answer, the one related directly to Isaiah, goes like this:

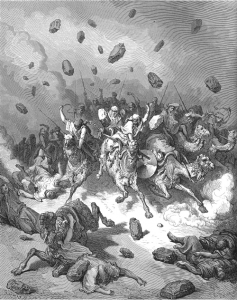

First, and corresponding to Schlobin’s first point, Isaiah presents a number of hair-raising apocalyptic scenes, especially in chapters 24-27 and 34, that show Yahweh reducing the world to a rubble that’s coeval with primeval chaos. The idea of such chaos, and the awful connotations associated with it, is a primary theme of all biblical literature. It’s one of the conceptual linchpins for understanding what this whole library of ancient texts is about. In Isaiah, Yahweh is perpetually threatening to destroy the world order because of human behavior that affronts his nature. From a purely literary standpoint, these apocalyptic scenes are located at key portions in the text that mark them as anchors of the book’s entire meaning. And they’re unbelievably bloody and violent in the way that only religious fantasies, especially those written by ancient people working in a premodern worldview, can be. So this establishes the book’s validity as a text that distorts normal cosmology.

Second, and corresponding to Schlobin’s third point (I decided to discuss them out of order in my paper, since it suited my purpose), Isaiah is positively drenched in a sense of Yahweh’s transcendent, terrifying otherness, in the manner of Otto’s words that I quoted a minute ago. The book is one of the key texts in the Hebrew canon that emphasizes Yahweh’s absolute holiness, which — significantly — isn’t so much a moral thing as a categorical thing. “Holiness” refers to the absolute otherness of Yahweh’s nature from the human point of view, not to any kind of pristine moral purity (although some would debate that claim). Combine this with the first point, and the picture starts to become clear: “What’s that, you say? An all-powerful and wholly other transcendent supernatural being that threatens to annihilate the cosmic order and reduce everything to primordial chaos? I sense the shade of Lovecraft.”

The third point of my argument, which addresses Schlobin’s second point about the way horror stories invert customary signs and meanings, focuses intensely on chapter 66, verse 24, which is in fact the final verse of the book: “And they shall go out and look at the dead bodies of the people who have rebelled against me; for their worm shall not die, their fire shall not be quenched, and they shall be an abhorrence to all flesh.” Yes, it’s the same verse that provided the title for my lead story in Divinations of the Deep. It’s spoken by Yahweh in an imagined scene after he has destroyed the world and created a new and blissful situation for those humans who remained true to him. What he’s describing is the perpetual desecration of the corpses of those who opposed him. This is presented as one of the primary components of the new post-apocalyptic world order: the corpses of Yahweh’s enemies suffer eternal putrefaction and violation, the eternal gnawing of worms and scorching of fire. And those who “shall go out and look at” these dead bodies are those whom Yahweh has saved. It’s almost as if it’s a holy duty for Yahweh’s protected ones to view this punishment. If you do the historical-critical thing and trace the significance of every piece of imagery in the passage, you find that it’s all very carefully constructed to invoke the precise things that would have aroused the greatest horror among ancient Hebrew readers. And its location as the closing verse of the text virtually shouts that this is the book’s final meaning, the point of closure toward which it has been striving. Ancient readers noticed this; there used to be an instruction in Jewish circles that whenever the final part of Isaiah was read aloud in the synagogue, the reading of 66:24 was to be followed by a repetition of 66:23 — a kinder, gentler verse — in order to avoid the shock of ending the reading with that scene of Yahweh’s awful wrath.

The third point of my argument, which addresses Schlobin’s second point about the way horror stories invert customary signs and meanings, focuses intensely on chapter 66, verse 24, which is in fact the final verse of the book: “And they shall go out and look at the dead bodies of the people who have rebelled against me; for their worm shall not die, their fire shall not be quenched, and they shall be an abhorrence to all flesh.” Yes, it’s the same verse that provided the title for my lead story in Divinations of the Deep. It’s spoken by Yahweh in an imagined scene after he has destroyed the world and created a new and blissful situation for those humans who remained true to him. What he’s describing is the perpetual desecration of the corpses of those who opposed him. This is presented as one of the primary components of the new post-apocalyptic world order: the corpses of Yahweh’s enemies suffer eternal putrefaction and violation, the eternal gnawing of worms and scorching of fire. And those who “shall go out and look at” these dead bodies are those whom Yahweh has saved. It’s almost as if it’s a holy duty for Yahweh’s protected ones to view this punishment. If you do the historical-critical thing and trace the significance of every piece of imagery in the passage, you find that it’s all very carefully constructed to invoke the precise things that would have aroused the greatest horror among ancient Hebrew readers. And its location as the closing verse of the text virtually shouts that this is the book’s final meaning, the point of closure toward which it has been striving. Ancient readers noticed this; there used to be an instruction in Jewish circles that whenever the final part of Isaiah was read aloud in the synagogue, the reading of 66:24 was to be followed by a repetition of 66:23 — a kinder, gentler verse — in order to avoid the shock of ending the reading with that scene of Yahweh’s awful wrath.

So I assume the full outline of my argument is pretty clear from all of this. Isaiah passes Schlobin’s three tests with flying colors. It can be validly read as a horror story. Of course, I pack the paper itself with much more detail that accounts for other parts of the text and shows how this reading is in fact internally consistent with the book’s overall content. It’s been said that the best interpretation is one that accounts for the most evidence. I tried and, I think, succeeded for the most part in accounting for Isaiah’s overall thrust in my horrific reading of it.

TheoFantastique: One of the more interesting and controversial facets of your argument for conservative Christians is the idea of the divine functioning as a monster. You state that “the biblical God is often portrayed as a source of horror as much as he is a source of comfort and blessing.” Can you say more about this idea, particularly in connection with Otto’s idea of “religious awe in ‘daemonic dread'”?

TheoFantastique: One of the more interesting and controversial facets of your argument for conservative Christians is the idea of the divine functioning as a monster. You state that “the biblical God is often portrayed as a source of horror as much as he is a source of comfort and blessing.” Can you say more about this idea, particularly in connection with Otto’s idea of “religious awe in ‘daemonic dread'”?

Matt Cardin: Otto’s The Idea of the Holy has become a touchstone text for a great many theoretical writers about horror and gothic fiction, and rightly so, I think. I’m sure many of your readers already know about his famous argument that the deep historical and psychological origin of the human religious impulse doesn’t lie in intimations and emotions of supernatural goodness and light but in a sense of “daemonic dread,” of uncanny fear and shuddering at the sense of an awesome presence. Otto took great pains to demonstrate that this emotion or intuition is entirely sui generis — unlike anything else, a special case of its own, irreducible to and unexplainable by any other experience – and he argued that it was the refinement, elaboration, and sublimation of this experience that gave rise to all of the higher religions. He also pointed out the obvious implications for horror fiction, namely, that the same emotion drives the genre.

To me, everything he says about the matter has the status of self-evident truth, because it corresponds to fundamental tropes in my own psyche. (And I am aware of the danger of falling into a kind of interpretive solipsism here.) It also helps to account for a huge amount of Christian biblical and theological material, as well as things from across the global religious spectrum, that are otherwise difficult or impossible to account for. Religion has always been associated with the same part of human experience that shows up in visions and — hint, hint — nightmares. The heads/tails nature of the relationship between the supernatural-as-blissful and the supernatural-as-horrific has always been obvious to everybody. The same ought to go for the flipside relationship between the idea of the biblical God in his infinitude, absoluteness, and transcendence as, on the one hand, infinitely reassuring, and, on the other hand, infinitely horrifying.

As for the reservations that conservative Christians may have about this issue, well, they’re welcome to them. It just makes the ideological spectrum all the more colorful. Of course, such people are engaged in an unacknowledged morass of hypocrisy and/or self-delusion, since their tradition really and truly does contain those Otto-esque intimations of daemonic-divine dread and monstrousness, and denying it won’t make it go away. But now I can feel myself wanting to start deploying Schlobin again by analyzing this conservative theological position in terms of Point Two, the inversion of signs and meanings, since I think many conservative Christians are prey to sentiments that resonate with the global über-violence of apocalyptic fantasies along the lines of the Left Behind craze, and their longing for such events to come to pass represents quite a moral inversion. So I’ll stop myself before I get started.

TheoFantastique: Your conclusion, then, is that Isaiah, at least in certain places, may be properly understood as horror literature? This is ironic in that Protestant evangelicals often have a knee-jerk reaction against certain forms of speculative fiction, particularly horror.

Matt Cardin: My conclusion is that Isaiah can be understood as a cosmic horror story, a la Lovecraft etc., in its entirety. All that’s required is a shifting of one’s surface focus and underlying assumptions. It’s not that some parts are horrific and others aren’t, but that the whole thing can be read and — importantly — emotionally experienced that way, while remaining entirely true to its concrete content. What’s at issue, what’s foregrounded, is the reader’s fundamental interpretive assumptions and — which I think may be even more important — emotional cast.

Note that one corollary of Otto’s insight is that religious/spiritual transcendence can be approached through daemonic dread. I think that’s part of my subterranean purpose here. That, and just laboring to articulate a textual/theological insight that was trying to claw its way out of me.

TheoFantastique: Matt, thanks again for sharing your thoughts. I wish you well with the book.

Immensely stimulating, thanks. I wonder what you make of the church fathers’ notion that Isaiah is ‘the Fifth gospel’?

Sam, thank you for your positive consideration of this interview. I feared it might result in negative Christian backlash, and while this can still come down the line, I hope your comment sets a tone for what may come. In my seminary courses on church history and New Testament I don’t remember the topic about which you raise your question, so I can’t comment on it. I do think, however, that the issue of apocalyptic is of enormous concern in horror in pop culture, and thoughtful Christians would do well to reassess this beyond the Left Behind nonsense so as to connect apocalyptic in Isaiah and the gospels to these contemporary cultural concerns.

Wow I had never thought of the Bible in this way before. Bravo for very original analysis and for sharing them with us!