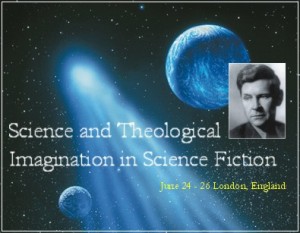

My daily search for all things fantastic in popular culture resulted in my stumbling upon an announcement for an intriguing conference on Science and Theological Imagination in Science Fiction:

My daily search for all things fantastic in popular culture resulted in my stumbling upon an announcement for an intriguing conference on Science and Theological Imagination in Science Fiction:

Science fiction is a twentieth-century invention. In it writers and readers try to imagine life in a context wider than our present — perhaps requiring as great a leap as members of a hunter-gatherer clan would have to make to comprehend a global, technological culture like our own. If science fiction is the literary exploration of the larger universe, religion is the body of beliefs and rituals that help to link the familiar worlds of human meaning and experience to that more sweeping and mysterious cosmos. Religion demands commitment to particular sets of stories about that world. Science fiction calls for a more self-conscious or ironic suspension of belief. The cause of religion has been served by great artists and saints (as well as villains); science fiction, so far, by rather few. Occasionally the two coalesce: what Manichaeism was, Scientology now is — deliberate fantastic structures devised by single artists and seized by the wider populace as devices to clear or cloud their heads. Other sects and cults arise by happenstance and the unforced agreement of many romantic minds gnosticism in the first century or the religion of Star Trek today. To consider the broader issues raised by science fiction and to explore, in particular, the relation of the genre to science and to theology, ten scholars, scientists, and writers gather in London on the seventieth anniversary of the publication of Last and First Men (1930), the first novel of the late writer and philosopher Olaf Stapledon (1886-1950), and a book often regarded as one of the finest works of science fiction. As the Year 2000 is also the fiftieth anniversary of Stapledon’s death, the conclave becomes an occasion to celebrate the author’s life. A question to be explored in both private conversation and in a public discussion is the impact of the existence of the universe in which science fiction attempts to find a place for humankind, a world immensely older and at once grander and more forbidding than we usually care to contemplate, on traditional religion. Other matters of inquiry include whether the genre sometimes known as “possibility writing” has given us useful clues to what it will mean to be human in the next millennium, how science fiction and the experience of working scientists may affect each other, what sort of challenge the search for the holy, which science fiction writers often locate in the alien, may pose to familiar religious preoccupations with right behavior or secular interest in peace and prosperity, whether science fiction can, in any useful sense, prepare us for an eventual meeting with other sentient beings — and the relative value of technological gadgets and moral systems in pursuing dialogue with them. Alternately, what if all the searches for life beyond the borders of Earth ultimately fail? What implications might that have for theology? The probe for answers in the conversation in London takes place under the aegis of the John Templeton Foundation.

This conference’s connection to the John Templeton Foundation, which has done some interesting work helping to heal the breach between religion and science, is interesting if not somewhat surprising. If only we had such conferences in the U.S.

I hope this will be recorded in some form or fashion and that we can get copies!