There is an essay in the Journal of Religion & Film worth checking out in Volume 16, Issue 1 (April 2012). It is by Richard Lindsay, and the title is “Menstruation as Heroine’s Journey in Pan’s Labyrinth.”

There is an essay in the Journal of Religion & Film worth checking out in Volume 16, Issue 1 (April 2012). It is by Richard Lindsay, and the title is “Menstruation as Heroine’s Journey in Pan’s Labyrinth.”

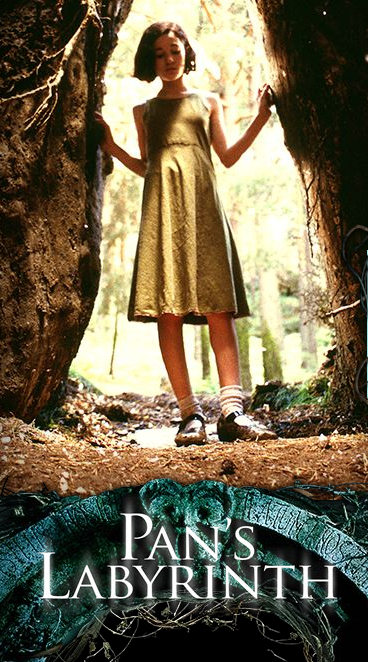

Lindsay’s article considers the myth of Pan’s Labyrinth through the lens of Joseph Campbell’s mythology, but one that is informed about criticisms and concerns in his approach to myth. With this analytical approach Lindsay notes that Guillermo del Toro turns the traditional mythology on its head by featuring a girl, Ofelia, as the main character who takes the hero’s journey. This feminine perspective is found throughout the film, from the characters in the film where Ofelia is mirrored in her journey in the fantasy world by an adult who experiences travails in the mundane world, to feminine imagery such as the Faun’s head which takes on the shape of female internal sexual organs. (Images that support the author’s argument can be viewed in an essay on the piece at Pop Theology.) To those who find this symbolism questionable, Lindsay quotes del Toro in an interview acknowledging the “uterine” concept behind the fantasy world of the film.

One aspect of the essay surprised me when Lindsay referenced another interview with del Toro, this one with the National Film Institute, where a connection was made between Pan’s Labyrinth and The Devil’s Backbone, del Toro’s earlier horror film. Here del Toro said:

I had to make a movie that structurally echoed Devil’s Backbone, and that you could watch back to back. Devil’s Backbone is the boy’s movie. It’s the brother movie. But Pan’s Labyrinth is the sister movie, the female energy to that other one. I wanted to make it because fascism is definitely a male concern and a boy’s game, so I wanted to oppose that with an 11-year-old girl’s universe.

Near the end of the essay Lindsay discusses the death of Ofelia and her “resurrection” in the fantasy underworld where she is a princess. This leads to a consideration of resurrection in fantasy and in religion. Here, del Toro’s concerns over his childhood Catholicism come through as he shares his distaste for resurrection in The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe, (a film he was asked to direct and declined) and by extension, resurrection as conceived of in Christianity. Even so, del Toro still seems to appreciate aspects of the passion story:

What is the worth of that sacrifice if he knows he’s coming back? I really enjoy the uncertainty of a guy or a creature going to die for something without knowing if there’s anyone to bail him out. What’s beautiful about the death of Jesus is him saying to his father, ‘Why have you forsaken me?’ That incredibly mysterious and moving passage is so precious because he doesn’t know. If he knew, screw that.

Richard Lindsay’s essay demonstrates the depth and complexity of Pan’s Labyrinth and the work of del Toro. His understanding of myth and religion come together to make for a cinematic experience that rewards repeated viewings and ongoing reflection.

3 Responses to “Menstruation as Heroine’s Journey in Pan’s Labyrinth”