In a recent film review of the new science fiction film Looper, James Pinkerton raised important questions related to science fiction and our utopian vision. In his essay “What ‘Looper’ tells us about the American vision,” Pinkerton opens his piece with the following thought provoking paragraph:

Which science-fiction scenario better describes the future: “Star Trek” or “Blade Runner”? That is, can we look forward to the utopian vista of “Star Trek,” in which we humans have solved the problems of earth, leaving the rest of the universe for us to explore? Or must we dread the smoggy dystopia of “Blade Runner,” in which a brutal world is divided starkly between the huddled poor and the rich luxuriating in their guarded enclaves?

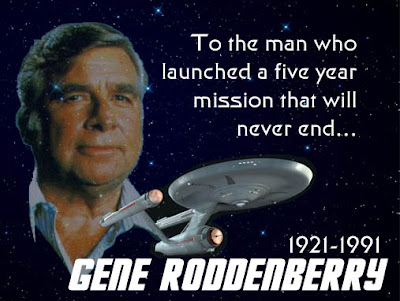

This might be a curious question to raise in what is ostensibly a film review for Looper, but the questions are worthwhile. Star Trek‘s original series recently celebrated its 46th anniversary, and Star Trek: The Next Generation celebrated its 25th. It’s influence continues to be felt, not only by Star Trek fans or in the science fiction subculture, but also in broader popular culture. One aspect of its continuing appeal comes with its utopian vision for humanity’s future. Birthed in the late 1960s when the counterculture hoped for a better way forward beyond the challenges of the times, Gene Roddenberry created a fictional world of the 23rd century wherein human beings moved beyond the challenges of racism, sexism, and war (and even religion), to unite human beings as they looked forward to their exploration of the universe. Earth’s united humanity joined with alien races as part of the United Federation of Planets, which postulated a technological utopia which has been carried through in each incarnation in the Star Trek franchise whether film or television.

This utopian vision was a part of Roddenberry’s own hopes for humanity, which sprang from his Secular Humanism. On more than one occasion Roddenberry would articulate his vision in words like this:

“I believe in humanity. We are an incredible species. We’re still just a child creature, we’re still being nasty to each other. And all children go through those phases. We’re growing up, we’re moving into adolescence now. When we grow up — man, we’re going to be something!”

This was Roddenberry’s dream, and one that human beings share across cultures. It has resonated so strongly with individuals that the secular dreams of Roddenberry became the ethic of Infinite Diversity in Infinite Combination, which has since ironically functioned in a religious sense for not a few Star Trek fans.

Roddenberry’s franchise may be the best example of science fiction’s articulation of the utopian dream. But almost fifty years since since Roddenberry’s vision came to the small screen should it still be viewed as a realistic goal and a prediction for what our future society will look like, whether nationally or internationally? Here an interesting parallel may be found in our current political debates with promises of hope and change tempered by requests for more time, with alternatives presented in the suggestion that we are on the wrong course. Is humanity working toward the Roddenberry utopia with more time needed to realize this dream, or are we on the wrong track living in dystopia perhaps with no possibility of societal redemption?

It is at this juncture that Pinkerton suggests that perhaps Blade Runner is a more realistic depiction of human society for the future. He writes,

But there’s still that “Star Trek” vs. “Blade Runner” business. If it’s true what they say–that sci-fi is as much a meditation on the present as a projection into the future–can we then deduce anything about our society from this particular film?

Pinkerton then sketches the historical developments since Roddenberry first shared his optimistic humanist vision. He notes that the national optimism in certain segments of American society of the late 1960s soon gave way to darker realities. As a result, “the big collective vision of Roddenberry seems, now, to be as far away as Alpha Centauri.”

In contrast with Roddenberry’s optimism, Pinkerton introduces the dark science fiction vision of Philip K. Dick. The dystopian influence of the film Blade Runner is still felt throughout science fiction as evident in the past from films like Terminator, to more recent efforts such as the remake of Total Recall to the new film Looper. Pinkerton contrasts the competing visions of these science fiction writers:

If Roddenberry stood for optimism, Dick stood for pessimism. To Roddenberry, the future was gleaming and beckoning; to Dick, the future was all going to be just a huge misunderstanding, if not an outright evil conspiracy. The protagonists in Dick’s stories may go to space, but if they come back at all, they come back haunted, unsure of such a basic question as their own identity.

As I read Pinkerton’s essay I was struck by the seeming failure of Roddenberry’s vision. Sure, we can argue that we just need more time, and given more education, more technology, more…you fill in the blanks, human beings can and will achieve something similar to Roddenberry’s dream. After all, he did place it in the 23rd century, which gives us roughly two hundred more years to work things out. But skeptics look at the past history of humanity, with its frequent predictions of utopia tempered by the reality of dystopia, and are inclined to doubt our future prospects. It would seem that perhaps Dick’s dark and pessimistic vision is the more accurate predictor of not only the future, but our present state of affairs.

Even so, Pinkerton acknowledges that thousands of people are still animated by Roddenberry’s utopian vision and still hold out hope that his ideals will be realized. The differing assessments of humanity’s future by Roddenberry and Dick represent two competing models from these prophets of science fiction.

Bradbury once noted that science fiction portrayed the future we wanted to avoid.

After reading your post, the first thing that popped into my head was Sterling’s opening for the Twilight Zone: “That’s the sign post up ahead – your next stop, the Twilight Zone”

That’s the future. We can speculate all we want, either as a conscious effort to chart out the territory or as an exercise in entertainment. But there is certainly no telling for sure.

In all likelihood, the world of 2300+ will be a mix of Dickian & Roddenberryian tropes, overlaid with some Heinleinian and Le Guinian, Haldemenian, Delanyian, Russian (read that carefully) and Butlerian.

Thanks for stopping by and commenting, Steve. Great to find out about your website.

I think it’s important to remember that Roddenberry’s future was not all utopian. It got TERRIBLE before it could ever get better (Eugenics Wars, World War III). Saying that our current trajectory seems to go against his utopian vision only means that we have yet to hit rock bottom and turn the corner he imagined. That said, I think the best argument against Roddenberry’s vision is the likelihood that humanity is just good enough never to hit rock bottom and just bad enough never to aspire to Roddenberry’s utopian greatness without doing so.