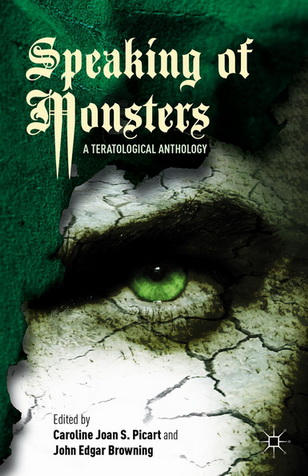

It was with great excitement that I heard about the book Speaking of Monsters: A Teratological Anthology (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), edited by John Edgar Browning. This volume provides an in-depth scholarly exploration of a number of facets of teratology, the study of monsters. It took us a while to finish this interview, but Browning made some time in a busy academic schedule to discuss monsters with TheoFantastique.

It was with great excitement that I heard about the book Speaking of Monsters: A Teratological Anthology (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), edited by John Edgar Browning. This volume provides an in-depth scholarly exploration of a number of facets of teratology, the study of monsters. It took us a while to finish this interview, but Browning made some time in a busy academic schedule to discuss monsters with TheoFantastique.

John Edgar Browning is Arthur A. Schomburg Fellow in the Department of Transnational Studies and an adjunct faculty member in the Department of English at SUNY-Buffalo. He has contracted and co-/written ten books, including Draculas, Vampires, and Other Undead Forms: Essays on Gender, Race, and Culture; Dracula in Visual Media: Film, Television, Comic Book and Electronic Game Appearances, 1921-2010; The Vampire, His Kith and Kin: A Critical Edition; Bram Stoker’s Dracula: The Critical Feast, An Annotated Reference of Reviews and Reactions, 1897-1920; and The Forgotten Writings of Bram Stoker. His work on horror and the fantastic has been published or is forthcoming in numerous anthologies and journals, including Film History, Horror Studies, Studies in the Fantastic, Dead Reckonings: A Review Magazine for the Horror Field, Victorian Literature and Culture, and Religion & Literature.

TheoFantastique: John, thank you for taking time out of a very busy schedule to talk about one of your recent books. How did you come to a personal interest in monsters, and how did this become an academic focus as well?

John Edgar Browning: My parents showed my brothers and me horror films from a very early age, so I guess you could say I took liking to them when I was barely out of kindergarten. Later, as I started to grow older, I began to see some of the socio-politics embedded in horror films in general, and monstrosity in particular. My own otherness—my burgeoning sexuality, low socio-economic standing, and generally tall stature—helped me, I think, to see these politics at play. During my undergraduate studied at Florida State, Dr. Caroline Picart, a prolific author and scholar of horror theory, showed me that my interest in the macabre could develop into something more; she also showed me the publishing “ropes,” and I went on to publish my first few books with her. She showed me I had wings (and perhaps even nudged me a little over the cliff).

TheoFantastique: Your approach to monsters is of great personal interest to me with this volume. Why should we pause and consider a teratology? Why are monsters the stuff of serious cross-cultural and cross-disciplinary study as well as perhaps pop culture wisdom?

John Edgar Browning: David J. Skal wrote in his foreword to the volume that “a constantly shifting conversation is the essence of survival when it comes to monsters.” Monsters engage in many conversations and socio-political discourses, and over time they change their minds, amend themselves, and adapt, and frankly they do this because we do this. They’re our politicians, and we pull the strings.

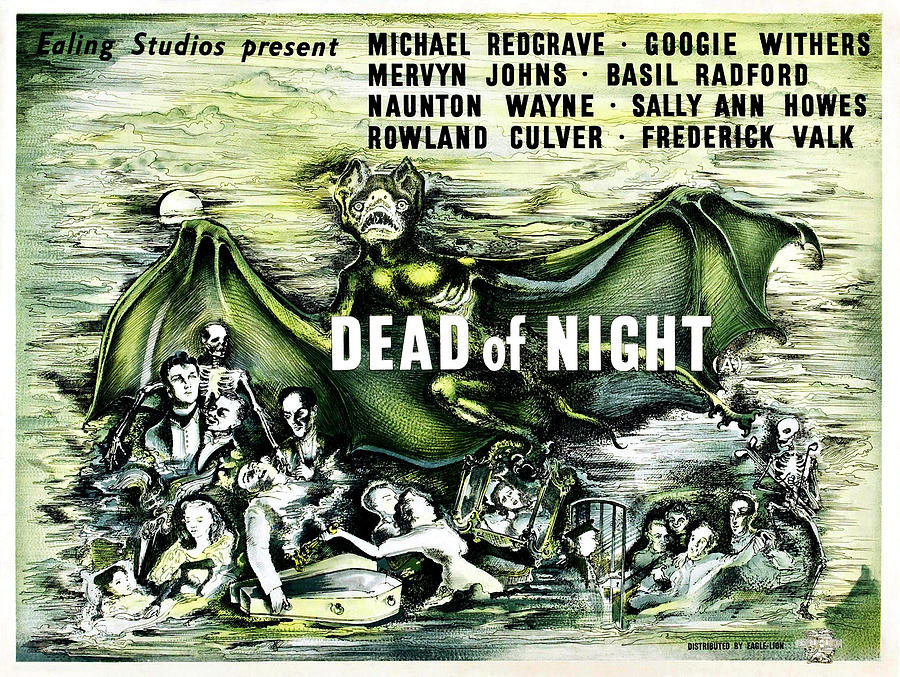

TheoFantastique: Mark Jancovich is a gifted writer on horror in my view. He discusses a neglected British horror film, Dead of Night, in his contribution to your book. Why was this film overlooked in 1940s horror films, and do you see any connection to this and the horror cycle that would emerge with Hammer Studios in the 1950s?

TheoFantastique: Mark Jancovich is a gifted writer on horror in my view. He discusses a neglected British horror film, Dead of Night, in his contribution to your book. Why was this film overlooked in 1940s horror films, and do you see any connection to this and the horror cycle that would emerge with Hammer Studios in the 1950s?

John Edgar Browning: As Jancovich explains, Dead of Night tended to be overlooked by critics of the genre because they were, in essence, using a much later model to classify Dead. The standards of “horror” and its associated aesthetics in Britain in the 1940s would, and indeed did (according to Jancovich), see Dead as horror/noir/“chiller.” Now, I believe, they call them noiror. It would be the same as having a ‘30s or ‘40s critic—or audience for that matter—view a modern gay film and wonder why it wasn’t being classified as horror (recall Countess Zaleska’s lesbianic character in Dracula’s Daughter [1936]).

TheoFantastique: In the volume’s second section, Margaret Carter contrasts perspectives on the monster slayer in Blood+ and Buffy the Vampire Slayer. What types of things does she draw out in similarities and differences between these conceptions, and how has America’s Buffy drawn upon Japanese concepts?

John Edgar Browning: Buffy, according to Carter, “pioneered several tropes and narrative techniques relatively new to American television” when the series premiered, but these same themes and markers “were already common in anime.” For example, the teenage girl in high school who doubles “as a monster-slaying heroine with a hidden identity,” “continuity with complex plotlines and character arcs extended over multiple seasons,” major characters frequently dying, and the hybridization of “disparate genres such as horror, romance, comedy, fantasy, and science fiction within a single” narrative framework. Carter observes further that, despite this cross-fertilization between American media and Japanese manga and anime, in Japanese narratives the absolute “other” simply does not belong; reconciliation is possible, and essentialized alterity is problematic at best.

TheoFantastique: One chapter was of particular interest to me as it explored religious monstrosity. Jason Bivins builds upon his look at problematic and horrific aspects of Evangelicalism in a previous volume, with a chapter on how religion often creates a monstrous Other. How do you see America’s religious monsters continuing to form and shape-shift in light of post-Christendom and a post-9/11 environment?

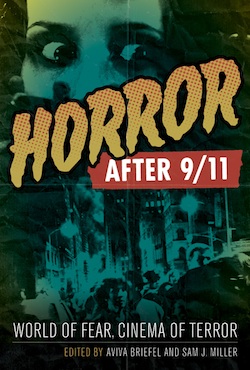

John Edgar Browning: My own personal hope is that we’ve started to see a slowing-down of religious othering; you’ll recall that this was, just after and for several years there forward, the monstre du jour after 9/11—American citizens wearing something even remotely resembling a turban, of any style, were being harassed. Bivins has done fine work in this field, and readers will also want to check out Aviva Briefel and Sam J. Miller’s Horror after 9/11: World of Fear, Cinema of Terror (University of Texas Press, 2011).

John Edgar Browning: My own personal hope is that we’ve started to see a slowing-down of religious othering; you’ll recall that this was, just after and for several years there forward, the monstre du jour after 9/11—American citizens wearing something even remotely resembling a turban, of any style, were being harassed. Bivins has done fine work in this field, and readers will also want to check out Aviva Briefel and Sam J. Miller’s Horror after 9/11: World of Fear, Cinema of Terror (University of Texas Press, 2011).

TheoFantastique: John, thank you again for the interview, and my best to you on your continued academic studies, writing, and editing.

John Edgar Browning: The pleasure is mine; keep up the outstanding work yourself.

There are no responses yet