I am privileged to be a part of the Peter Cushing Centennial Blogathon spearheaded by Pierre Fournier at his wonderful blog Frankensteinia. Be sure to visit the blog to see the other posts in this blogathon. Peter Cushing has been one of my favorite horror actors for many years, and out of the many iconic characters he portrayed, Dr. Van Helsing has always been the most interesting for me. In this contribution to his centennial blogathon, I will consider Cushing’s portrayals of Van Helsing, and by drawing upon the analytical perspective of Heather Duda on the monster hunter in popular culture, I will consider how Cushing’s Van Helsing makes for a stark contrast with the 2004 cinematic incarnation of the same character portrayed by Hugh Jackman.

I am privileged to be a part of the Peter Cushing Centennial Blogathon spearheaded by Pierre Fournier at his wonderful blog Frankensteinia. Be sure to visit the blog to see the other posts in this blogathon. Peter Cushing has been one of my favorite horror actors for many years, and out of the many iconic characters he portrayed, Dr. Van Helsing has always been the most interesting for me. In this contribution to his centennial blogathon, I will consider Cushing’s portrayals of Van Helsing, and by drawing upon the analytical perspective of Heather Duda on the monster hunter in popular culture, I will consider how Cushing’s Van Helsing makes for a stark contrast with the 2004 cinematic incarnation of the same character portrayed by Hugh Jackman.

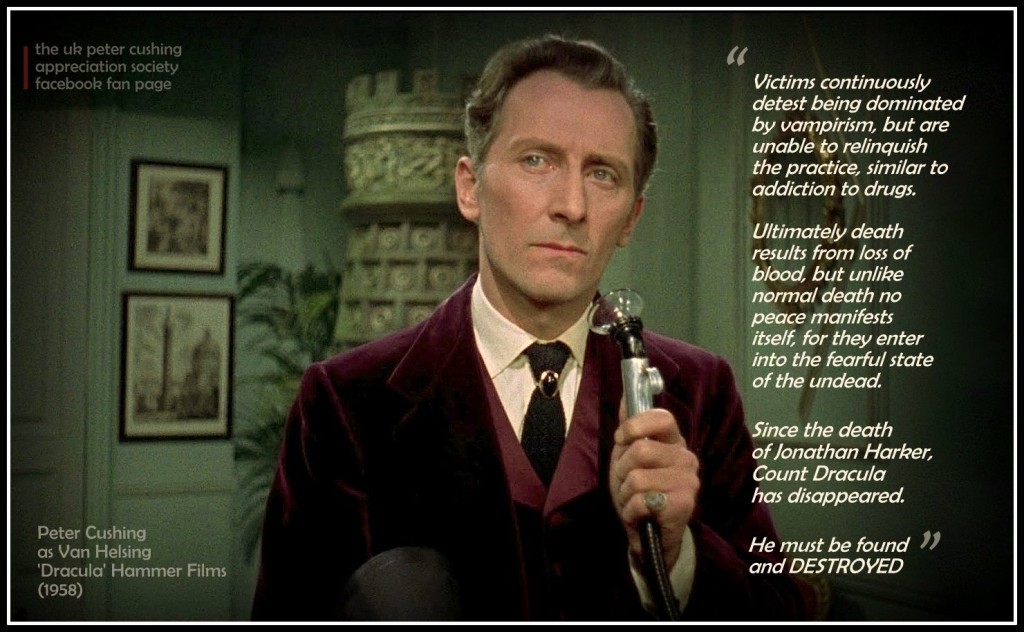

Peter Cushing played various expressions of the Van Helsing vampire hunter in a number of films. This includes Horror of Dracula (1958), The Brides of Dracula (1960), Dracula: Prince of Darkness (1966), Dracula: A.D. 1972 (1972), The Satanic Rites of Dracula (1973), and The Legend of the 7 Golden Vampires (1974). Of course, these incarnations of Van Helsing have a connection to Bram Stoker’s character, and in what follows we will sketch the significance of this iconic figure and how he changes over time.

In her book The Monster Hunter in Modern Popular Culture (McFarland, 2008), Heather Duda addresses the monster hunter as a largely neglected aspect of monster studies. She argues that Stoker’s novel Dracula “is the epitome of the monster-hunting narrative,” and that Van Helsing stands out as the “ultimate monster hunter” functioning as binary opposite of Dracula as “the ultimate monster.” What kind of man was Van Helsing? Stoker provided a description by way of the character John Seward in the novel:

He is a philosopher and a metaphysician, and one of the most advanced scientists of his day; and he has, I believe, an absolutely open mind. This, with an iron nerve, a temper of the ice-brook, an indomitable resolution, self-command toleration exalted from virtues to blessings, and the kindliest and truest heart that beats […] work both in theory and practice, for his views are as wide as his all-embracing sympathy.

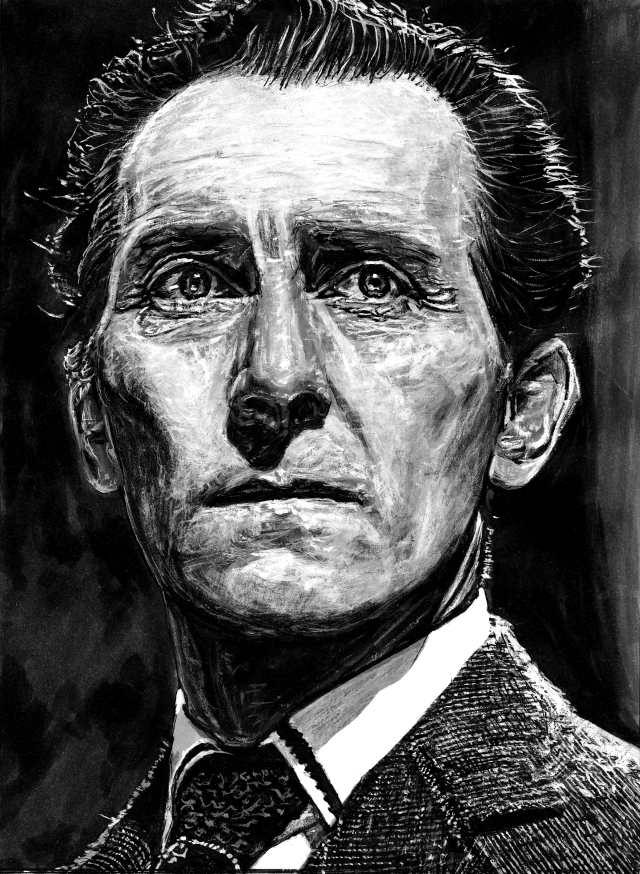

Stoker’s Van Helsing was based upon the Victorian ideal of the male here, and Cushing brought the essence of this to life much like Seward’s description. This is best illustrated in his first portrayal of Van Helsing in Horror of Dracula. First, He is presented as a learned man, a philosopher and metaphysician, the latter understood in terms of the secular scientist drawing upon the symbols of Catholicism for its magical properties in dispatching the vampire. In one scene n another scene Van Helsing records the results of his ongoing research into a phonograph, and this provides us with a glimpse of his academic expertise. In another scene we discover how significant this is as he touts his vampire research to Arthur Holmwood as having been done for “some of the greatest authorities in Europe.” This is no amateur, but instead an educated scholar who brings together an interesting synthesis of folklore studies, philosophy, metaphysics, and science. Second, Cushing’s Van Helsing is much like Stoker’s in that he has a kind heart. He goes to the grave of the undead Lucy in order to release her from her curse, and while there he rescues the a little girl, the would-be victim of the new vampire. With Lucy resting in her coffin at the approach of the morning sun, Van Helsing exercises compassion toward the girl by wrapping his coat around her and giving her his cross to hold. Third, Cushing’s Van Helsing demonstrates the iron nerve of Stoker’s character at the climax of the film when he chases Dracula into his castle. After almost being bitten and narrowly escaping, he doesn’t run from the castle to fight another day, but instead stares back at the Count before pulling down the curtains and using the sun and two candlesticks formed into a cross as the improvised weapons of monster hunting.

Cushing would go on through various films and not only play this particular Dr. Van Helsing again, but also his descendants. Regardless of the expression of Van Helsing, his character always worked to defeat the monster, and in so doing re-establish the status quo, both in the Victorian-influenced world of the Gothic horror of these Hammer films, but also that reflected in the times in which these films were made. But in our cultural journey out of the Victorian era, into the 1930s with Edward Van Sloan’s depiction of Van Helsing, and moving into Hammer’s depictions of the character in the 1950s and into the 1970s, our understanding of the monster and the monster hunter changed. So did Van Helsing. He would eventually go to his grave and a new generation of monster hunters would arise.

Duda argues that films like The Fearless Vampire Killers (1967) and Captain Kronos: Vampire Hunter (1974) are worthy of consideration because they were significant in the development of the monster hunter. The involve various shifts and additions. In these films the emphasis is on the monster hunter himself rather than on the creatures he stalks. And in Kronos the monster hunter no longer works alone, but gains an assistant or sidekick. There is also a change in the monster hunter in that the emphasis is no longer on him being the learned man who can outsmart his monstrous adversary. Now audiences expect a young and physically attractive hero. These developments continue in films like Blade, and go on to influence conceptions of the monster hunter in the 21st century.

In 2004 Hugh Jackman provided his take on Van Helsing in the film of the same name, and it is here that the transformation from the character is most striking, particularly how different from both Stoker’s conception, and Cushing’s depiction. Duda points out that between Cushing’s depictions of Van Helsing that started in the late 1950s and Jackman’s decades later, the United States had wrestled with the events that shook the national psyche, like Vietnam and Watergate. The impact of these events on the national consciousness changed the way in which both the monster hunter and his prey were viewed. The previous developments in depictions of the monster hunter with films like Kronos discussed above, coupled with the impact of the culture’s political angst, would come together to shape a very different portrayal of Van Helsing. Jackman’s “hero” is a man wanted by the law, a hired henchman rather than a learned and highly prized man. This element combines aspects of both a blurring of the monster and monster hunter, and distrust inherent in all authority figures In terms of appearance, he embodies contemporary standards of male masculinity and beauty, with long hair and an unshaven face. He no longer works alone, but has an assistant, Carl, and he must also draw upon the best high-tech weaponry and fighting techniques of the time.

A comparison of the character of Van Helsing in different eras reveals significant differences that reflect their times. Jackman’s Van Helsing represented the late modern conception of the hero and the monster hunter. The clear line between good and evil is blurred at best, as is that between monster and the monster hunter. Cushing’s Van Helsing was crafted with the assumptions of an earlier age. He represented both a depiction of the Victorian ideal for the hero, and the conception of the monster hunter prevalent in the late 1950s. This resulted in a confident, educated man with an inner beauty of character and virtue. As a fine British actor and gentleman, Cushing was the perfect choice to bring this conception of Van Helsing as the ultimate monster hunter to life.

You make a good point about changes in the depiction of monster hunters. We could probably trace the changes all the way back to Beowulf. I suppose Peter Cushing and perhaps Edward Van Sloan, Lugosi’s Van Helsing, were the only horror movie actors who were famous for playing good guys. Thank you for sharing this with us.

Very interesting. The shift in the image of the hero and the blurring of lines between monster and hunter adds yet another layer to the stories we enjoy. Much food for thought. Personally, I do lean toward the prized, learned man.

Excellent and thoughtful analysis – a wonderful post! Thank you!

Craig

Fellow Peter Cushing Centennial Blogathon participant

http://craiglgooh.blogspot.com/