From time to time a select few are given the opportunity to contribute guest posts here at TheoFantastique. This essay is by Brandon Engel, who looks back at one of the classic 1970s science fiction films.

From time to time a select few are given the opportunity to contribute guest posts here at TheoFantastique. This essay is by Brandon Engel, who looks back at one of the classic 1970s science fiction films.

There’s something incredibly unnerving (uncanny, if you must) about non-human entities that are similar to humans in either form or function. Freud wrote extensively on the subject, as did Ernst Jentsch. Both felt that dolls, robots, and other automata induce a sort of miniature-existential crisis in viewers, who are inclined to project human emotions and motivations unto the objects, and perhaps even wonder about whether or not the dolls are secretly alive. There is something especially unsettling about a plastic facial expression, frozen in time.

And just what are the implications of an animate object coming to life, and being endowed with the ability to make conscious decisions? What sort of moral compass would inform its decision making (if any), and would it be capable of acting compassionately? In the 21st century these types of questions are especially pressing with concerns over our technology in the form of artificial intelligence, robotics, and drones, particularly as they are used in military and law enforcement settings.

This is a recurring theme in science fiction: technology endowed with too much autonomy (a la 2001: A Space Odyssey), and, inversely, human beings who are relegated to perfunctory roles like cogs in a larger mechanism (a la Fritz Lang’s Metropolis).

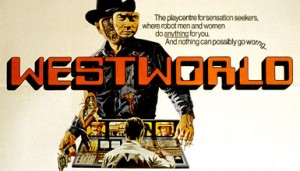

A film that handled the subject in a distinctly seventies genre pulp way is Michael Crichton’s Westworld. Crichton, who gets a lot of recognition for his work as a novelist, contributed a tremendous amount to the world of fantasy filmmaking. Along with make-up artist Stan Winston and director Steven Spielberg, he brought Jurassic Park to the world, and forever changed the way that children from the nineties look at theme parks. Crichton had done the same thing to children in the seventies with Westworld, his feature film directorial debut.

Westworld fuses multiple genres, including elements of western, science fiction, and horror films. The film tells the story of the Delos resort, comprised of three different theme parks (one based on ancient Rome, another based on 13th Century Europe, and a third park representing the “wild west” complete with saloons, old-timey prostitutes, horses, and shoot-outs. The “townsfolk” of Westworld are all animatronic puppets (much like the ones you’d see on the Pirates of the Caribbean ride at Disneyland) supplied to give pleasure to the vacationer who is there to live out their wild west fantasy. The whole vacation package costs $1,000 per day. The robots are engineered so that they can’t harm human guests, but something goes grievously wrong…

The film stars screen-legend Yul Brynner, warmly remembered by many fans for his roles in The King and I and The Man Who Would Be King. In Westworld, Brynner plays a mechanical cowboy — an amusement park attraction that instigates supposedly safe gun-fights with park guests. His character is based on the Chris Adams character that Brynner himself portrayed in The Magnificent Seven. Visitors are given firearms that are harmless on other humans but kill androids. People can shoot and kill the robot. Normally, the robot is taken to a repair shop in order to be put in working order for the next day. The robots malfunction, though, and end up shooting people. One of the film’s most memorable scenes is in the saloon with Peter Martin (Richard Benjamin, from television’s “He and She”) and John Blane (James Brolin, best known as “Marcus Welby’s” Dr. Steven Kiley.) The two are friends who decide to vacation at Westworld.

The film stars screen-legend Yul Brynner, warmly remembered by many fans for his roles in The King and I and The Man Who Would Be King. In Westworld, Brynner plays a mechanical cowboy — an amusement park attraction that instigates supposedly safe gun-fights with park guests. His character is based on the Chris Adams character that Brynner himself portrayed in The Magnificent Seven. Visitors are given firearms that are harmless on other humans but kill androids. People can shoot and kill the robot. Normally, the robot is taken to a repair shop in order to be put in working order for the next day. The robots malfunction, though, and end up shooting people. One of the film’s most memorable scenes is in the saloon with Peter Martin (Richard Benjamin, from television’s “He and She”) and John Blane (James Brolin, best known as “Marcus Welby’s” Dr. Steven Kiley.) The two are friends who decide to vacation at Westworld.

The biggest similarity between Jurassic Park and Westworld is, obviously, that both deal with amusement parks attractions that have gone haywire and start killing people. In Jurassic Park, the problems are started initially by the geneticists’ oversight (the dinosaurs are constructed partially from the DNA of gender-switching amphibians, which means that the dinosaurs begin mating autonomously). In Westworld, there is a sort of computer virus that begins to infiltrate all of the robots.

The Seventies was an interesting time for imaginative (if not slightly paranoid) intellectuals like Crichton. On the one hand, the economy was still quite strong, and as a natural consequence of that, the well to do we’re living extravagantly. The consumer culture was thriving, and privileged sects of society sought after new excesses. At the same time, the horrors of World War II, and grim musings about the potential misapplications of technology (or notions of technology as a liability to humanity) permeated pop culture. Westworld is at once a sort of sardonic joke about post-World War II consumerism and the grandiosity of something like Disneyland, but it also poses a lot of poignant “what if’s” regarding the inherent risk factors with man essentially “playing God” by constructing these alternate realities inhabited by human-like objects (presumably devoid of any kind of conscience).

Harvard graduate Michael Crichton had an illustrious career across several disciplines, and he achieved monumental success by an early age. Crichton’s first novel, “Odds On”, was published in 1966. His directorial debut film was Westworld, a project that Crichton had originally envisioned as a novel, but ultimately decided to pursue as a film. The script was turned down by every major studio except MGM.

Of all of his early cinematic efforts, Westworld has the largest cult following. The film has been enjoying a recent resurgence in popularity and even shows regularly at art houses and on TV it’s been appearing regularly on El Rey Network, which has increased visibility of the film because it reaches DIRECTV, Comcast and some Netflix subscribers. After the success of Westworld, Crichton would go on to direct 6 more films including Looker with Albert Finney, and Coma with Michael Douglas. He would go on to achieve much as a novelist and screenwriter, but Westworld was his crowning achievement as a film director.

Brandon Engel is a Chicago-based blogger with a keen interest in genre pulp literature and vintage cult films. Follow him on Twitter: @BrandonEngel2

Yes, I remember those SF movies of the late sixties and early seventies–2001, Planet of the Apes, Soylent Green, Westworld, Logan’s Run … How I liked them. (I didn’t take to Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, for some reason.)