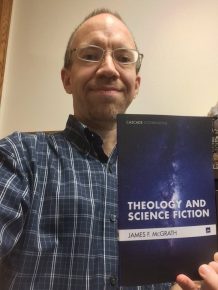

James McGrath and I share common interests in theology, religion, and science fiction. When these things merge together it’s even better. McGrath, Clarence L. Goodwin Chair in New Testament Language and Literature at Butler University in Indianapolis, Indiana, has a new book out, Theology and Science Fiction, and he shares his thoughts about this subject in the interview below.

James McGrath and I share common interests in theology, religion, and science fiction. When these things merge together it’s even better. McGrath, Clarence L. Goodwin Chair in New Testament Language and Literature at Butler University in Indianapolis, Indiana, has a new book out, Theology and Science Fiction, and he shares his thoughts about this subject in the interview below.

TheoFantastique: James, thanks for carving out some time to discuss your book. I appreciated the approach. Let’s unpack that a bit. As you note in the book, there tends to be certain approaches to the topic from either the religious believer looking for confirmation of their faith through the genre, or from more hard science fiction advocates who tend to use the genre as a way of dismissing religion and religious commitments. You are hoping that theology and science fiction will engage in mutual dialogue and reflection. How did you arrive at this perspective?

James McGrath: Thanks for the opportunity to talk about this book, which has been a really exciting project for me. The view I adopt, which you mention, reflects, on the one hand, my experience that I learn a great deal from those who disagree with me and challenge my views and assumptions; but on the other hand, as I mention in the introduction to the book, it reflects my exploration of the different models for the relationship between theology/religion on the one hand, and science on the other. Ian Barbour discusses the options of conflict, independence, dialogue, and integration. One can apply these, I think, to science fiction as well. One can fight, or agree to a truce that delineates a border. But just as many of us hope that people can get beyond fighting or awkward separation to conversation and eventually cooperation, it seems to me appropriate to hope that these two traditions might likewise be viewed not as enemies or as distinct others but as at least interesting conversation partners, and at best collaborators in the quest to explore and reflect on our place in the cosmos. For (as I hopefully argue persuasively in the book) they have more in common already than either might initially realize.

TheoFantastique: What would you say to the conservative religious believer scandalized by the prospect that theology can learn from science fiction?

James McGrath: I would be delighted if they are scandalized – being challenged, provoked, and stretched is – or at least, can be – a good thing! I think that conservative religious people who express antipathy towards science fiction need to ask whether they have not embraced it without even realizing it – just as some conservative Christians will use the rhetoric of rejection of contemporary values and norms, and yet not notice how much they in fact reflect the cultural values and assumptions of their country. When conservative Christians turn the Book of Revelation into a story about a global conspiracy involving a single world government, strange disappearances, and mysterious occurrences, they are borrowing more from the spirit of The X-Files than from ancient apocalyptic. And when conservative religious people claim that UFOs are demons, they are simply a mirror image of the “ancient aliens” perspective that says that ancient demons and gods were in fact alien visitors. And so I hope those coming from that perspective will be provoked and moved to reflect and wrestle with questions such as why, if sci-fi is not something that theology can learn from, they appear to have learned and borrowed so much from it.

TheoFantastique: What would you say to the secular science fiction advocate who wants to keep theology at arms length from science fiction?

James McGrath: I would point out how much theology is present even – perhaps especially – in secular science fiction. When Captain Kirk discusses the attributes a god ought to have in “Where No Man Has Gone Before,” or says that “Apollo’s no god – but he may have been mistaken for one once” in “Who Mourns for Adonais?” and when Teal’c on Stargate rejects Apophis as a false god, these characters are not merely giving voice to a secular, anti-religious viewpoint. They are engaging in theology. One cannot hope to define what makes a being a “false god” or “no god” without theology, because the domain that explores such questions is theology. There is no avoiding it. While some would like to simply dismiss the entire enterprise, the only way forward is to engage in it, and to ask whether one can justify a theological stance that can embrace the existence of powerful beings from the skies and yet deny their divinity. But atheism and Christianity might agree too much on that point for the comfort of the modern adherents of either.

TheoFantastique: How has your own understanding and appreciation of theology and science fiction changed and been stretched perhaps by your studies?

James McGrath: I wrote the book because I already had appreciation for both. And so I really appreciate this question, because as you hint and are presumably already aware, even if one recognizes from the outset that a conversation is important and worthwhile, if one engages in it fully, one cannot fail to be changed and transformed in the process. One of the many ways that I was transformed, personally, by this project, was that I pursued getting some of my own short science fiction stories published, and wrote a new one that is included in this volume. Science fiction seems to me to not only be something that one might read in order to reflect – it can also be something that one can write in one’s effort to reflect, explore, and/or give expression to one’s own faith. As a Christian and sci-fi fan myself, exploring the intersection is not just an academic interest. It challenges me to fully engage my imagination, to embrace the power of narrative, and to ask hard questions not only about what we know and can hope to know as human beings, but what we dare to hope. Looking together to the future, the perspectives of theology and science fiction both have the potential to offer visions of faith – not predictions that reflect the problematic view that prophecy is about getting the details of the future right, but hopes for the future whose primary value is in the way that they can challenge us to live differently in the present in light of that vision of the future which, whether right or wrong in many of its details, calls to us to move boldly in its direction.

TheoFantastique: James, thanks again for the opportunity to read this book and reflect on this fascinating topic further.

Love this quote:

When conservative Christians turn the Book of Revelation into a story about a global conspiracy involving a single world government, strange disappearances, and mysterious occurrences, they are borrowing more from the spirit of The X-Files than from ancient apocalyptic. And when conservative religious people claim that UFOs are demons, they are simply a mirror image of the “ancient aliens” perspective that says that ancient demons and gods were in fact alien visitors.