While listening to Christmas music today I caught a part in one of the lyrics for “It’s the Most Wonderful Time of the Year” that mentioned telling scary ghost stories. I posted an inquiry on Facebook about the origins of this in the evolution of Christmas, and in addition to its incorporation in Victorian practices, Justin Mullis, who will be making a presentation on the American appropriation of Austria’s Krampus traditions at the 2017 meeting of the American Academy of Religions, posted the following:

While listening to Christmas music today I caught a part in one of the lyrics for “It’s the Most Wonderful Time of the Year” that mentioned telling scary ghost stories. I posted an inquiry on Facebook about the origins of this in the evolution of Christmas, and in addition to its incorporation in Victorian practices, Justin Mullis, who will be making a presentation on the American appropriation of Austria’s Krampus traditions at the 2017 meeting of the American Academy of Religions, posted the following:

if you look into the history of Christmas you’ll see that our modern conception of the holiday as a time of peace and goodwill is a very recent innovation. Historically Christmas was, to steal a phrase from researcher Al Ridenour, “a time of supreme supernatural mayhem.” For example in his excellent book Slayers and Their Vampires: A Cultural History of Killing the Dead, Bruce A. McClelland notes that in certain Eastern European countries…

“…the ‘twelve days of Christmas,” from Christmas Eve through Epiphany, or Jordan’s Day (January 6), are known as the ‘Unclean Days.’ Other names for this period are quite revealing: they include ‘Pagan Days,’ ‘Ember Days,’ ‘Unbaptized Days,’ and even ‘Vampire Days.’ This brief midwinter period represents a time when, it is believed, evil spirits are able to roam the earth…In South Slavic belief, people who die during this period invariably become vampires. Also, children who are born or conceived during this period have special powers and may themselves become vampires.” (pages 56-57)

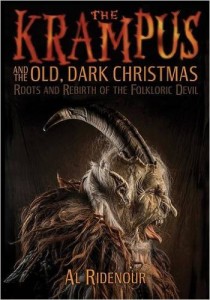

Likewise, Ridenour in his new book, The Krampus and the Old Dark Christmas, writes…

“Though it’s hardly a feature of the modern horror film, up until at least 1860, according to German Folk Superstitions of the Present, Christmas and werewolves went hand in hand. The seasonal fear of these beasts was so great that simply to utter the word ‘wolf’ between Christmas and Epiphany (or even during the entire month of December) was to put oneself at risk… to be born on Christmas Day could be considered an affront to Christ and thereby result in one being cursed to life as a werewolf.” (page 155)

In addition to vampire, werewolves and demons like the Krampus, witches and ghosts were also once a regular part of Christmas time festivities. For a fairly exhaustive overview of Christmas witch traditions I would again recommend Ridenour’s book, but also John Grossman’s Christmas Curiosities: Odd, Dark and Forgotten Christmas. Also Phyllis Siefker’s Santa Claus, Last of the Wild Men for more on the Krampus and related traditions and Siefker’s argument that Santa evolved not from St. Nicholas but rather from the medieval wildman.

In addition to vampire, werewolves and demons like the Krampus, witches and ghosts were also once a regular part of Christmas time festivities. For a fairly exhaustive overview of Christmas witch traditions I would again recommend Ridenour’s book, but also John Grossman’s Christmas Curiosities: Odd, Dark and Forgotten Christmas. Also Phyllis Siefker’s Santa Claus, Last of the Wild Men for more on the Krampus and related traditions and Siefker’s argument that Santa evolved not from St. Nicholas but rather from the medieval wildman.

As for ghosts, it was indeed once a time honored part of British and American Christmas to tell ghost stories. Dicken’s A Christmas Carol is, of course, the most famous example but the tradition is far older. In 1589 Christopher Marlowe writes in the Jew of Malta that: “Now I remember those old women’s words, Who in my wealth would tell me winter’s tales, And speak of spirits and ghosts that glide by night.” A hundred years later no less then Shakespeare himself notes in A Winter’s Tale, that: “A sad tale’s best for winter: I have one. Of sprites and goblins.”

In America, Washington Irving writes of the tradition of telling Christmas Ghost Stories in 1819 in From The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent, and a few years later in 1845 Poe sets his Raven “in the bleak December; And each separate dying ember wrought its ghost upon the floor.” After Poe, H.P. Lovecraft added The Festival to the canon of Christmas chillers in 1923 in which he astutely observed that: “It was the Yuletide, that men call Christmas though they know in their hearts it is older than Bethlehem and Babylon, older than Memphis and mankind.”

Back in Britain, writer M.R. James transformed the practice of the Christian Ghost story into an institution that endures to this day via the BBC’s A Ghost Story for Christmas; a strand of annual British short television films originally broadcast on BBC One between 1971 and 1978, and revived in 2005 on BBC Four. James was a key influence on Henry James, who in The Turn of the Screw, published in 1898 wrote: “The story had held us, round the fire, sufficiently breathless, but except the obvious remark that it was gruesome, as, on Christmas Eve in an old house, a strange tale should essentially be, I remember no comment uttered till somebody happened to say that it was the only case he had met in which such a visitation had fallen on a child.”

A Christmas Carol was not Dickens’ only contribution to the genre of scary Christmas stories either. In The Story of the Goblins who Stole a Sexton in 1837 about a mean old gravedigger who is dragged down to the underworld by a band of goblins on Christmas Eve – perhaps a reference to certain Scandinavian traditions that associate Christmas, once again, with the darker side of the supernatural: in this case trolls, goblins, fairies and elves – that later of which have managed to stick around albeit in a highly sanitized form.

As for why these traditions haven’t stayed as prominence as others – I would say they have gone away – in the United States that is probably an even more complicated question to answer then the history I’ve just laid out. The increasing commercialism or Christmas? Conservative Christians attempting to expunge any latent pagan elements from the holiday? I sometimes wonder – as author Jeanette Winterson recently suggested in an interview with The New Yorker regarding her new book of supernatural tinged Christmas stories – if the official formation of Halloween as a holiday didn’t have something to do with it. Today Halloween is our ‘scary’ holiday and Christmas is our ‘joyful’ one. To have two holidays both centered around the sinister side of the spirit world so close together would seem redundant and so all the ghosts, goblins, vampires, witches, monsters, and werewolves got relegated to Halloween, forced out of the Christmas holiday they previously owned.

There are no responses yet