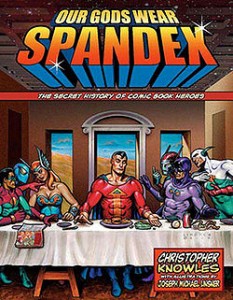

Comic books and graphic novels are not only popular sources for television and Hollywood films. They are also increasingly the object of academic and critical scrutiny. Christopher Knowles has made his own contribution in this area with his book Our Gods Wear Spandex: The Secret History of Comic Book Heroes (Weiser Books, 2007). As the back cover of the books asks, “Was Superman’s arch nemesis Lex Luthor based on the early twentieth-century occultist Aleister Crowley? How is Batman linked to the Kabbalah?” Knowles suggests that the answer to these and similar questions is a resounding “yes” as paganism and Western esotericism has served as an influence in comic books. He probes this topic in the following interview.

Comic books and graphic novels are not only popular sources for television and Hollywood films. They are also increasingly the object of academic and critical scrutiny. Christopher Knowles has made his own contribution in this area with his book Our Gods Wear Spandex: The Secret History of Comic Book Heroes (Weiser Books, 2007). As the back cover of the books asks, “Was Superman’s arch nemesis Lex Luthor based on the early twentieth-century occultist Aleister Crowley? How is Batman linked to the Kabbalah?” Knowles suggests that the answer to these and similar questions is a resounding “yes” as paganism and Western esotericism has served as an influence in comic books. He probes this topic in the following interview.

TheoFantastique: I recently read a piece online which discussed the impact of H. P. Lovecraft on comics. You discuss his literary work, and that he was a self-professed atheist, but you mention that some question whether he had esoteric interests and connections given the cosmology and mythology he constructed. What types of esoteric influences have some attributed to Lovecraft, and regardless of his metaphysical views, how do you see him as an influence on contemporary comics?

Christopher Knowles: Well, a lot of the discussions of Lovecraft’s immersion in the occult have been from occult partisans. Kenneth Grant, who was head of the Ordo Templi Orientis, comes to mind here. Lovecraft was obviously aware of the occult since it was very much part of the pulp milieu- the counterculture of its time. I think he may have read some occult texts — maybe some Theosophical or Rosicrucian material — since he was a voracious reader and was looking out for story material. But Lovecraft to me was a guy who was very much in touch with an aspect of the unconscious mind that nightmares dwell in, night terrors, hallucinations — things like that. I think that was a much more powerful influence on him than occultism, which can get so nebulous as to include anything. Lovecraft really did the occultism of his time one better and created a more immersive universe than you could with spells or incantations. He’s an occult order unto himself.

Christopher Knowles: Well, a lot of the discussions of Lovecraft’s immersion in the occult have been from occult partisans. Kenneth Grant, who was head of the Ordo Templi Orientis, comes to mind here. Lovecraft was obviously aware of the occult since it was very much part of the pulp milieu- the counterculture of its time. I think he may have read some occult texts — maybe some Theosophical or Rosicrucian material — since he was a voracious reader and was looking out for story material. But Lovecraft to me was a guy who was very much in touch with an aspect of the unconscious mind that nightmares dwell in, night terrors, hallucinations — things like that. I think that was a much more powerful influence on him than occultism, which can get so nebulous as to include anything. Lovecraft really did the occultism of his time one better and created a more immersive universe than you could with spells or incantations. He’s an occult order unto himself.

TheoFantastique: One of the types of comic heroes as gods that you put forward is the Golems, based upon Jewish mysticism. I was surprised by the great number of comic heroes you included in this list, but they seem to fit. Why are there so many comic heroes that have been influenced by this form of comic mysticism?

Christopher Knowles: Here’s basically how I see it with the archetypes I named — The Messiah is the daddy fantasy, the Amazon is the mommy fantasy, the Brotherhood is the fantasy group of friends but the Golem is us. The Golem is the one who suffers and who wants revenge. The one who feels victimized and needs armor to cover the wounds. So when the general audience drifted away the comics were being read by hardcore fans, who often feel marginalized and victimized. So you’re going to have a built-in audience for this archetype from kids who feel a need to vindicate, to avenge wrongs done to them.

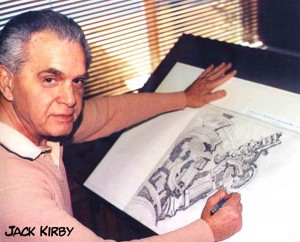

TheoFantastique: I appreciated your discussion in the chapter called “The Visionaries” where you mention key figures who helped develop our “gods in spandex.” The first and perhaps most influential is Jack Kirby. Many fans of Kirby’s work will likely be surprised to learn of his infusion of mysticism in his comics. How did he come to produce a body of work that you describe as “fundamentally psychedelic and intrinsically pagan”? And how has Kirby been influential on other visionaries, whether in comics or other venues?

TheoFantastique: I appreciated your discussion in the chapter called “The Visionaries” where you mention key figures who helped develop our “gods in spandex.” The first and perhaps most influential is Jack Kirby. Many fans of Kirby’s work will likely be surprised to learn of his infusion of mysticism in his comics. How did he come to produce a body of work that you describe as “fundamentally psychedelic and intrinsically pagan”? And how has Kirby been influential on other visionaries, whether in comics or other venues?

Christopher Knowles: Well, how Kirby became Kirby is the $64,000 question. Kirby had a pretty rough and tumble childhood and then had an unusually traumatic experience in the war. He also was almost autistic in the sense that he existed inside his head and projected those stories from his mind onto the paper. Then something extremely strange happens to him and he undergoes this metamorphosis in the mid-60s and his art becomes very primitive and very futuristic at the same time, but also extremely psychedelic. It has a frightening similarity to shamanic art from the ayahuasca cults and the rest of it. At the same time he’s tapping into this ancient, archaic visionary mindset he’s also becoming obsessed with the aliens and UFOs and comes right out and says that all of these ancient astronaut stories he starts doing with the Fourth World and the Eternals and the rest of it are him being “mystical.” That’s the word he uses. It gets to the point that he’s working over these themes in the art he does for himself, the paintings like Incan Visitation and the Bible portfolio.

As to who he influenced, everybody doing anything with sci-fi or superheroes has been influenced by Kirby, whether they realize it or not.

TheoFantastique: How might Alan Moore’s work be seen as incorporating his interest in ritual magic?

Christopher Knowles: I’m not sure I can answer that exactly, other than the very literal stuff he wrote for Promethea. I was really disappointed in that series, because it was a comic that was magic and became a comic about magic. Big difference there. But by the same token I think the League of Extraordinary Gentlemen is the best work anyone’s done as far as superhero teams go, bar none. I don’t think anything can touch it. So he can answer this better than I, but I’d guess he’s allowed himself to really explore the depths of his psyche and really dig deep into what storytelling is, which is a much more powerful form of magic than anything else I can name.

Christopher Knowles: I’m not sure I can answer that exactly, other than the very literal stuff he wrote for Promethea. I was really disappointed in that series, because it was a comic that was magic and became a comic about magic. Big difference there. But by the same token I think the League of Extraordinary Gentlemen is the best work anyone’s done as far as superhero teams go, bar none. I don’t think anything can touch it. So he can answer this better than I, but I’d guess he’s allowed himself to really explore the depths of his psyche and really dig deep into what storytelling is, which is a much more powerful form of magic than anything else I can name.

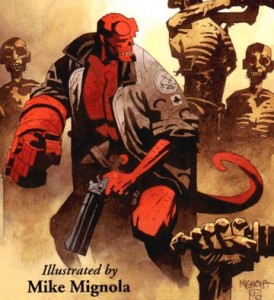

TheoFantastique: How does Mike Mignola incorporate occult history in his comics?

Christopher Knowles: How doesn’t he? It’s really what his work is about. All of his writing digs into lore that most people have forgotten. I have this weird picture of him sitting there by lamplight, poring over some dusty grimoire that was written on the tanned skin of virgins back in the Dark Ages. I can just see the demons and spirits and jinns leaping from the darkness into this imaginary magical quill Mignola is holding that allows him to force them to do his bidding. I’m really sorry he doesn’t do much drawing anymore because the magic comes when he’s riding all the horses, but I understand it. He scares the hell out of me because he makes it all so real, yet intensely hilarious at the same time.

TheoFantastique: At one point near the end of your book you write:

TheoFantastique: At one point near the end of your book you write:

“Comic-book fans are a small, but highly dedicated and influential group. They usually develop an intense, intimate relationship with the comics medium at an early age, often as a result of childhood trauma. Many have a general disposition toward shyness or social awkwardness that tends to cement their dedication to the form, turning them into, in Stan Lee’s words, “true believers” indistinguishable from your average theology student or seminarian.”

As a former seminarian and comic fan I identified with this statement. Do you find this as a general tendency in your work among comic fans?

Christopher Knowles: Well, my experience with comic fans is past tense now, but sure. One of the reasons the book was so controversial was because the average fan loved it and the hardcore fan thought it was heresy. And they also thought I was telling tales out of school. Hardcore fans tend to form very intense, subjective and personal bonds with the medium, and tend to shut out anyone else’s relationship to the material. That’s why you can go to a comics store and see a bunch of middle aged guys trying their damnedest to ignore each other, even though they spend their days surrounded by people who have no idea what any of this comics stuff is about at all. It’s very much an escape from the rest of the world, which you also see in monasteries, strangely enough.

TheoFantastique: I strongly resonated with two brief paragraphs in your concluding chapter:

“We live in extremely depressing and disheartening times, in which old certainties vanish before our eyes. The world we once knew is either collapsing or being systematically dismantled, and there is nothing we can do about it. The daily political and economic bad news and the constant drumbeat of war and terrorism are making superhero fantasies more relevant and visceral, as well as more comforting and reassuring, than at any time since World War II.

“American religion seems unable to provide a viable salvation myth in this time of crisis. Most denominations have become nothing more than badly disguised political movements, interested only in money and power. On the other hand, our bloodless secular culture has no room in it for wonder. It should not surprise us then, when Harry Potter, Star Wars, and The X-Men step in to fill the void.”

I tend to agree, and would slightly modify your statement in that I wonder whether much of American Christendom likewise lacks wonder, mystery, transcendence, and a sense of inspiring mythic stories every bit as much as secular culture. Given this present state of affairs, what do you think not only about the future of comic’s potential as entertainment in pop culture, but also its potential to incorporate the supernatural, the spiritual, and the esoteric?

Christopher Knowles: I don’t know about comics in and of themselves. I think there’s a kind of winding down feeling about the market lately. There’s been a real risk-averse mentality at the big companies that has to do with the economics of publishing, which are pretty scary at the moment. I think that comics and superheroes have this common history but may not have a common future, necessarily. Superheroes might well belong onscreen and not on the page, now that the technology has caught up with the storytelling. I loved the Watchmen movie — to me it stomps all over the comic, as heretical as it is to admit. Same with Kick Ass.

The thing is that comics are the best place to take risks and really explore the possibilities but we don’t seem to value that in the culture. This is a really terrible time for this country, but also for the culture and the only way we’re going to get out of it is by using our creativity and imaginations. I don’t see that same energy in comics to kickstart that I did five or ten years ago. Other media tend to cherrypick the best creators and it’s very hard for new creators to get noticed. We’re starting to see the migration to the internet and to social media, but we’re still not seeing the magic yet. This might be a transitional period. But there’s a whole century of inspiration to explore that incorporates all of those themes, usually unconsciously. And the great news here is that a talented creator can create a universe with a pencil.

TheoFantastique: Chris, thanks again for your book and for probing its thesis and contents a little more deeply here.

Related post:

A correction: Kenneth Grant was the head of the what was once referred to as the Typhonian Ordo Templi Orientis, it is now the Typhonian Order. This is not to be mistaken with the Caliphate, or the Ordo Templi Orientis. The two Orders deal with completely different forms of esotericism and have been at odds int he past about which order are the true Crowleyan heirs.