The Open Graves, Open Minds Project unearthed depictions of the vampire and the undead in literature, art, and other media, before embracing shapeshifting creatures (most recently, the werewolf) and other supernatural beings and their worlds. It opens up questions concerning genre, gender, hybridity, cultural change, and other realms. It extends to all narratives of the fantastic, the folkloric, the fabulous, and the magical. Supernatural Cities encourages conversation between disciplines (e.g. history, cultural geography, folklore, social psychology, anthropology, sociology and literature). It explores the representation of urban heterotopias, otherness, haunting, estranging, the uncanny, enchantment, affective geographies, communal memory, and the urban fantastical.

The Open Graves, Open Minds Project unearthed depictions of the vampire and the undead in literature, art, and other media, before embracing shapeshifting creatures (most recently, the werewolf) and other supernatural beings and their worlds. It opens up questions concerning genre, gender, hybridity, cultural change, and other realms. It extends to all narratives of the fantastic, the folkloric, the fabulous, and the magical. Supernatural Cities encourages conversation between disciplines (e.g. history, cultural geography, folklore, social psychology, anthropology, sociology and literature). It explores the representation of urban heterotopias, otherness, haunting, estranging, the uncanny, enchantment, affective geographies, communal memory, and the urban fantastical.

The city theme ties in with OGOM’s current research: Sam George’s work on the English Eerie and the urban myth of Old Stinker, the Hull werewolf; the Pied Piper’s city of Hamelin and the geography and folklore of Transylvania; Bill Hughes’s work on the emergence of the genre of paranormal romance from out of (among other forms) urban fantasy; Kaja Franck’s work on wilderness, wolves, and were-animals in the city. This event will see us make connections with the research of Supernatural Cities scholars, led by historian Karl Bell. Karl has explored the myth of Spring-Heeled-Jack, and the relationship between the fantastical imagination and the urban environment. We invite other scholars to join in the dialogue with related themes from their own research.

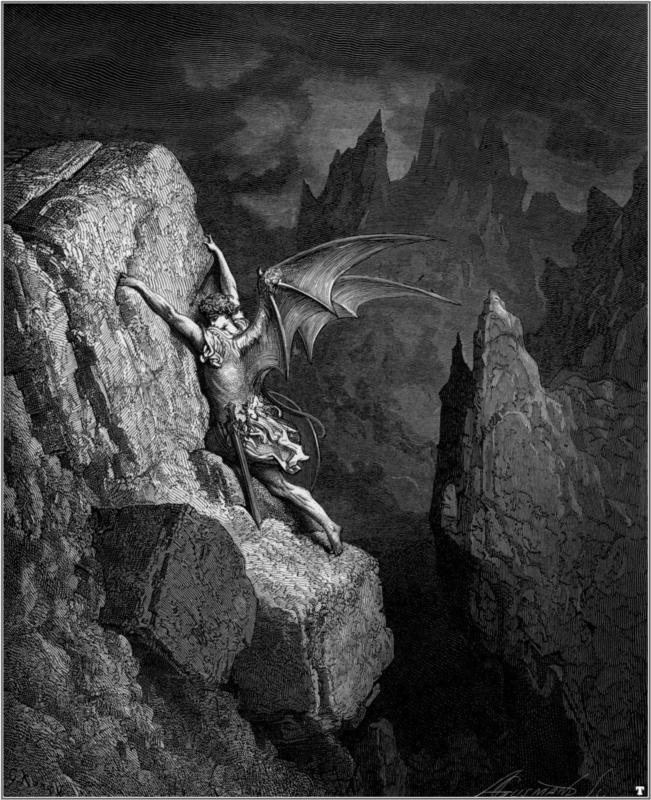

From its inception, the Gothic mode has been imbued with antiquity and solitude, with lonely castles and dark forests. The city, site of modernity, sociality, and rationalised living, seems to be an unlikely locus for texts of the supernatural. And yet, by the nineteenth century, Dracula had already invaded the metropolis from the Transylvanian shadows and writers such as R. L. Stevenson adapted the supernatural Gothic to urban settings. Gaskell, Dickens and Dostoyevsky, too, uncover the darker side of city life and suggest supernatural forces while discreetly maintaining a veneer of naturalism.

In twentieth-century fantastic and Gothic, perhaps owing in part to a disillusionment with modernity, all manner of spectres haunt our cities in novels, film, TV, and video games. Radcliffean Gothic saw the uncultivated wilderness and the premodern past as the fount of terror; the contemporary fantastic discovers the supernatural precisely where space has been most rationalised—the modern city. Civilisation, rooted etymologically in the Latin civitas (‘city’), is itself put into question by its subversion by the supernatural.

Supernatural cities emerge in a range of contemporary fictions from the horror of Stephen King to the dark fantasy of Clive Barker, the parallel Londons of V. E. Schwaab and China Mieville, magical neo-Victorian Londons in the Young Adult fiction of Genevieve Cogman and Samantha Shannon, and Aliette de Bodard’s fallen angels and dragons in a supernatural Paris. Zombies lurch through scenes of urban breakdown while, in TV, there is the vampire-ridden noir LA of Angel. The large metropolises are not alone in their unearthliness—see the Celtic otherworld that lies behind Manchester in Alan Garner’s Elidor. Then there are the imagined cities of high fantasy, which form a contrast to the gritty familiarity of the cities that feature in the distinct genre of urban fantasy itself or the frequently urban backgrounds of paranormal romance. Supernatural cities are haunted, too, by such urban legends as Spring Heeled-Jack and Old Stinker, the werewolf of Hull.

The conference will explore the image of the supernatural city as expressed in narrative media from a variety of epochs and cultures. It will provide an interdisciplinary forum for the development of innovative and creative research and examine the cultural significance of these themes in all their various manifestations. As with previous OGOM conferences, from which emerged books and special issue journals, there will be the opportunity for delegates’ presentations to be published.

The conference organising committee invites proposals for panels and individual papers. Possible topics and approaches may include (but are not limited to) the following:

The urban wyrd

The English eerie

Folk horror’s encroachment on the city

Magical cities

Alternative/parallel cities

Urban folklore/legends

Urban fantasy and genre

YA and children’s magical cities

Monsters and demons at large in the city (Dracula, Dorian Gray, Angel, Cat People, King Kong, Elephant Man, The Werewolf of London, Sweeney Todd, Jack the Ripper, Lestat, Zombie ‘R’, mummies, witches, etc.)

Psychogeography

Gothic architecture

Cities and the incursion of the wilderness

Civilisation and nature

Alternative urban histories; neo-Victorianism and steampunk

Gothic/magical fashion, music, and subcultures of the city

Supernatural city creatures (demons, gargoyles, ghosts, vampires, angels)

Animal hauntings and city spectres

Decay, entropy, and economic collapse

Supernatural cityscapes in video games

Gotham City/comic books/dark knights

The disenchantments of modernity and re-enchantment of the city

Dark spaces/borders/liminal landscapes

Wild, uncanny areas of the city

Drowned/submerged cities

Keynote Speakers:

Prof. Owen Davies, historian of witchcraft and magic, on ‘Supernatural beliefs in nineteenth-century asylums’

Dr Sam George, Convenor of the Open Graves, Open Minds Project, ‘City Demons: urban manifestations of the Pied Piper and Nosferatu Myths’

Adam Scovell, BFI critic and Folk Horror film specialist, on ‘the Urban Wyrd’

Dr Karl Bell, Convenor of Supernatural Cities, on ‘the fantastical imagination and the urban environment’ (title tbc)

Delegates will engage with our Gruesome Gazetteer of Gothic Hertfordshire and accompany us on a tour of Supernatural St Albans and its environs.

Abstracts (200-300 words) for twenty-minute papers or proposals for two-hour panels, together with a 100-word biography, should be submitted by 1 January 2018 as an email attachment in MS Word document format to all of the following:

Dr Sam George, s.george@herts.ac.uk;

Dr Bill Hughes, bill.enlightenment@gmail.com;

Dr Kaja Franck, k.a.franck@gmail.com;

Dr Karl Bell, karl.bell@port.ac.uk

Please use your surname as the document title. The abstract should be in the following format: (1) Title (2) Presenter(s) (3) Institutional affiliation (4) Email (5) Abstract. Panel proposals should include (1) Title of the panel (2) Name and contact information of the chair (3) Abstracts of the presenters.

Presenters will be notified of acceptance by 30 January 2018. Visit us at OpenGravesOpenMinds.com and follow us on Twitter @OGOMProject @imaginetheurban

I’ve just become aware of a new book based upon a PhD dissertation. It’s titled

I’ve just become aware of a new book based upon a PhD dissertation. It’s titled  Terry Wright of the

Terry Wright of the  The Open Graves, Open Minds Project unearthed depictions of the vampire and the undead in literature, art, and other media, before embracing shapeshifting creatures (most recently, the werewolf) and other supernatural beings and their worlds. It opens up questions concerning genre, gender, hybridity, cultural change, and other realms. It extends to all narratives of the fantastic, the folkloric, the fabulous, and the magical. Supernatural Cities encourages conversation between disciplines (e.g. history, cultural geography, folklore, social psychology, anthropology, sociology and literature). It explores the representation of urban heterotopias, otherness, haunting, estranging, the uncanny, enchantment, affective geographies, communal memory, and the urban fantastical.

The Open Graves, Open Minds Project unearthed depictions of the vampire and the undead in literature, art, and other media, before embracing shapeshifting creatures (most recently, the werewolf) and other supernatural beings and their worlds. It opens up questions concerning genre, gender, hybridity, cultural change, and other realms. It extends to all narratives of the fantastic, the folkloric, the fabulous, and the magical. Supernatural Cities encourages conversation between disciplines (e.g. history, cultural geography, folklore, social psychology, anthropology, sociology and literature). It explores the representation of urban heterotopias, otherness, haunting, estranging, the uncanny, enchantment, affective geographies, communal memory, and the urban fantastical. My complete panel list for Salt Lake Comic Con. Some great and thought provoking discussions, two of which I moderate.

My complete panel list for Salt Lake Comic Con. Some great and thought provoking discussions, two of which I moderate.

The boundary between the animal and the human has long been unstable, especially since the Victorian period. Where the boundary is drawn between human and animal is itself an expression of political power and dominance, and the ‘animal’ can at once express the deepest fears and greatest aspirations of a society’ (Victorian Animal Dreams, 4).

The boundary between the animal and the human has long been unstable, especially since the Victorian period. Where the boundary is drawn between human and animal is itself an expression of political power and dominance, and the ‘animal’ can at once express the deepest fears and greatest aspirations of a society’ (Victorian Animal Dreams, 4).