A few days ago an essay came across my daily Google news feed on horror that caught my attention. It was “Why Are So Many Horror Films Christian Propaganda?” by Josiah M. Hess at VICE. My initial reaction to the title was one of intrigue and thankfulness for the issue being raised, but this was accompanied by disagreement in that the idea of propaganda seemed a stretch. I posted a link to the piece in my TheoFantastique Facebook group and solicited thoughts from members there. But over the last few days I’ve had a chance to read and reflect on Hess’s essay, and as a result I felt I had some more extensive thoughts on his perspective that I wanted to share with readers.

A few days ago an essay came across my daily Google news feed on horror that caught my attention. It was “Why Are So Many Horror Films Christian Propaganda?” by Josiah M. Hess at VICE. My initial reaction to the title was one of intrigue and thankfulness for the issue being raised, but this was accompanied by disagreement in that the idea of propaganda seemed a stretch. I posted a link to the piece in my TheoFantastique Facebook group and solicited thoughts from members there. But over the last few days I’ve had a chance to read and reflect on Hess’s essay, and as a result I felt I had some more extensive thoughts on his perspective that I wanted to share with readers.

Let me state at the beginning that Hess and I are coming at this topic from radically different vantage points in terms of our metaphysical commitments. Hess identifies himself as a former evangelical and now an atheist, and I approach the topic as someone with religious commitments, a moderate evangelical. These different vantage points don’t necessarily predetermine our perspectives on the topic so long as we try to account for our biases along the way. Of course, if we don’t properly account for our biases they may indeed skew our understanding of the issues.

Starting with the title, Hess’s essay is far reaching in its claims. Horror films have a long history, and the title of his essay gives the impression that it is not just a particular time period or type of horror films that are allegedly examples of Christian propaganda, but instead horror films in general are problematic. To make sure the reader understands what he means by his title question, Hess defines it for us. After mentioning the blatant Christian evangelistic and apologetic films God’s Not Dead and Left Behind, Hess leaves no doubt in how he sees things.

But there’s another genre that seems to have the same proselytizing agenda that champions Christianity and demonizes all other faiths (including the faithless): horror movies.

Let’s be clear that we understand what Hess is arguing here. He is claiming that there are a large number of horror films that should be understood as Christian propaganda because they have a proselytizing agenda, they champion Christianity, and they denigrate other religions and irreligion. He is not merely claiming that there is a strong influence of Christianity in many horror films produced in the West because of the long history of Christianity as the dominant religion. He’s making an altogether different claim. But can he substantiate it? Are these films produced with the intent of being a form of propaganda, or do other explanations serve better to explain this phenomenon?

In the paragraphs that follow Hess develops his argument. He draws from a small pool of examples, the oldest going back only to the 1970s with The Exorcist. I understand the limitations on a writer in terms of the number of examples that can be cited, but the references he makes to argue his case provide another indication that Hess is overreaching in the title of his piece. He seems to be concerned about a smaller number of films, and have a more recent cinematic time frame in view.

Hess devotes a couple of paragraphs to the discussion of the basic formula for many horror films, particularly of late, that involve a Christian framework on spirituality and supernatural evil. Tales of demonic possession, use of “tools of Satan” such as Ouija boards, and exorcism, continue to be popular staples in American horror films. But does the inclusion of a Christian framework of supernaturalism and spiritual evil make a film Christian propaganda? I believe other considerations provide a better explanation.

I’ve been fascinated by the continued presence of Christian demonic and possession films and have wondered why they remain so popular, particularly in light of the decline in the credibility of Christianity as a metanarrative in the West in a post-Christendom culture, and the resulting demographic shifts that accompany this in terms of the loss of membership in American Christianity represented by groups like “The Nones.” I quoted Scott Poole in a past post, where he says that “the devil played a significant, and at moments determinative, role in the shaping of the American religious and popular imagination.” This is still going on. How then do we explain this? First, although Christianity is in decline in America, it has a long history here, and it has contributed significantly to the mythic reservoir of ideas. It is only natural then that filmmakers would tap into that as a way of finding narrative structures and specific ideas in order to tell horror stories that will resonate with audiences. To modify a popular phrase, “You can take the individual out of Christianity, but you can’t take the Christianity out of the individual.” Second, and related to the first idea, we have a continued psychological fascination with exorcism and demonic possession. I’ve discussed this in a previous post. The point to take away from this is that there are other good, and I think better, reasons why Christian supernatural evil continues to surface in contemporary horror films. We don’t have to posit propaganda to account for this.

As Hess continues, he recognizes that “not all horror films serve as mouthpieces for Christianity”, but he takes exception to those that “either condemn the faithless”, “frame non-Jesus religions as spooky”, or set forth biblical prophecy as fulfilled. He mentions The Conjuring, The Rite, The Wicker Man, The Exorcist, Sinister, Legion, and The Omen in connection with these concerns. Several thoughts by way of response came to mind as I read this paragraph by Hess. To begin with, I am sensitive to his concerns about the condemnation of other religions and irreligion, whether in horror or other public forums. As an atheist sharing his disagreements with what he sees as Christian horror, Hess is obviously not averse to taking exception to the perspectives of others in a public forum. I agree with him here, but this needs to be done with understand, respect, and fairness. We can and will disagree with each other over irreconcilable truth claims, but we must do so in ways that fairly represent the other, and with civility. I admit that American Christians, particularly evangelicals, have often framed those in other religions as literally demonic. And in surveys, Muslims and atheists have ranked at the bottom in how the public feels about them, so I am sympathetic to Hess’s concerns here.

However, the films Hess references in this section of his essay are a mixed bag. While some may draw upon a Christian supernatural framework and conception of spiritual evil, they do so in very different ways. In an essay for Cinefantastique Online I discussed “The Changing Face of Biblical Horror & Fantasy Films,” where a post-Christendom and postmodern framework is in view. In these contexts even though a Christian metanarrative is drawn upon, it often does so by way of critique and subversion of source material. It is not presenting Christianity as a positive force for propaganda. (The interested reader who wants to pursue my arguments on this in more depth can reference the article above, as well as my review of Legion.)

Hess goes on and says the he sees little difference “between the message I was taught by my church … and that of many scary movies.” But he goes further.

But the real question is: Are the producers of these films intentionally feeding us Christian propaganda (the way Communists in Hollywood were accused of poisoning minds in the 40s and 50s), or are they just using cultural devices that we’re familiar with in order to scare us?

As the title of his essay indicates, Hess argues for the former rather than the latter. In his view, the religious message of a Sunday school class and sermon is little different from many horror movies. And it’s not just a questionable religious message that’s put forward, it’s a form of propaganda that may be understood as a toxic influence designed to manipulate others in favor or a larger agenda of persuasion that he illustrates by with a reference to Communism. Hess follows these questions with quotations from two scholars, Hector Avalos and David Morgan. Hess believes many of these films “are explicitly Christian propaganda with a missionary agenda.” The Conjuring and Conjuring 2 are cited as examples of this. Morgan takes a contrary position. He refers to Morgan’s view as one where “[m]ost horror filmmakers aren’t so overt in their proselytizing, and possible don’t have any conscious religious agenda at all.” And yet later Hess says this scholar “doesn’t believe that they qualify as Christian propaganda.” If they don’t qualify in this regard in Morgan’s view, then it’s not a matter of them being less overt or that they don’t have an implicit religious agenda. Hess unfortunately softens Morgan’s perspective because he doesn’t agree with his alternative point of view. Morgan also claims that these films are drawing upon “a cultural currency,” a point I’ve made above.

While Hess concedes Morgan’s point about cultural currency, he goes on to share his concerns that the demonic elements of this currency comes from “the church or scary movies,” and these are “usually absorbed in childhood,” a time when we are at our most vulnerable, and not able to assess things “either on the basis of science or rationality.” I agree that Christian children are taught about supernaturalism and spiritual evil in church contexts, but this doesn’t necessarily constitute propaganda. Children imbibe any number of worldviews, religious and irreligious, from their parents, authority figures, and institutions. Is Hess arguing that this should stop, or that it is only appropriate when it is accompanied by science and rational argument, thus giving young people the tools that he feels will necessarily result in the rejection of religious “superstition”?

Hess then devotes a couple of paragraphs to the “nefarious implications” and “real-life consequences” of this alleged Christian propaganda in horror. He refers to The Witch (2015) and the victims of 17th century Puritan witch hunts that were accused of being in league with the devil and put to death, and present day examples where this continues to happen in places like Nigeria. I am in agreement with Hess in his disgust with and condemnation of these actions, but I don’t believe that by drawing upon a dark period in America’s religious history filmmakers are acknowledging that the victims of these events were justifiably executed. I think the opposite is true. On many levels the film functions as a critique of Puritan Christianity and its views on supernatural evil, as well as the subjugation of women and nature. In postmodern fashion The Witch draws upon the Christian metanarrative in combination with familiar horror tropes in order to challenge the assumptions upon which it is based.

After reading and reflecting on Hess’s essay I don’t believe he offers readers a good argument that supports his thesis. Yes, some filmmakers are Christians and they incorporate elements of their faith in order to present a moral and theological message. Scott Derrickson, as well as Chad and Carey Hayes are examples of this. Other filmmakers are not Christian, and they produce horror films that involve elements of a Christian worldview, including supernaturalism and spiritual evil. But this is best understood as cases of filmmakers tapping into the mythic reservoir of ideas that includes the religious imagination for the purposes of storytelling, not a purposeful attempt at proselytizing through propaganda.

In the beginning of this post I mentioned the importance of accounting for our biases. In my view Hess has not properly addressed his own negative experiences with Christianity in the past as interpreted in the present through his atheism. This then colors his interpretation of horror with Christian elements. Just as many conservative Christians have a knee-jerk reaction against horror due to their assumptions, I have the same impression about Hess having an equal and opposite reaction due to his atheism. For Christian fundamentalists horror is off limits because it opens individuals to spiritual contamination. For an atheist like Hess horror films are problematic because they are poisoned by religion and open individuals to contamination of their rational faculties. I hope that the assumptions on both sides can be carefully reassessed.

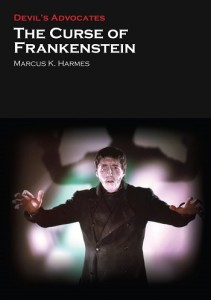

The Curse of Frankenstein by Marcus K. Harmes (Columbia University Press, June 2015)

The Curse of Frankenstein by Marcus K. Harmes (Columbia University Press, June 2015)