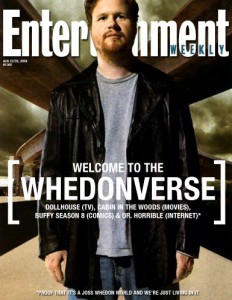

From time to time TheoFantastique explores aspects of fan cultures, and with this interview we talk to Tony Mills who discusses his contribution on the “Buffyverse Fandom as Religion” in Fan Phenomena: Buffy the Vampire Slayer, edited by Jennifer K. Stuller (University of Chicago Press, 2013). Tony Mills received a PhD in theology and culture from Fuller Seminary, where he studied theology and film under Robert Johnston and wrote a dissertation on theological anthropology and Marvel superhero comics and films, which will be released by Routledge later this year under the title American Theology, Superhero Comics, and Cinema.

From time to time TheoFantastique explores aspects of fan cultures, and with this interview we talk to Tony Mills who discusses his contribution on the “Buffyverse Fandom as Religion” in Fan Phenomena: Buffy the Vampire Slayer, edited by Jennifer K. Stuller (University of Chicago Press, 2013). Tony Mills received a PhD in theology and culture from Fuller Seminary, where he studied theology and film under Robert Johnston and wrote a dissertation on theological anthropology and Marvel superhero comics and films, which will be released by Routledge later this year under the title American Theology, Superhero Comics, and Cinema.

TheoFantastique: Let’s begin with some discussion of the book you’ve contributed a chapter to. How did you come to develop an interest in pop culture fandom and religion, and how does your contribution fit within the focus of Fan Phenomena?

Tony Mills: Hmmm, I don’t recall all of the details to answer the first part of your question. I’m part of a listserv which sends out various calls for papers and I was particularly intrigued by the one for the Fan Phenomena series which Intellect Books is currently doing. I was most interested in and familiar with Buffy, so I took some time to think of how my background in religion and theology could be used to give insight into fan phenomena. So I believe that call for papers was itself the impetus. As for the second part of your question, my contribution tries to get to the roots of why people become fans, especially dedicated ones. I’m interested in the biological and psychological impulses behind devotion and how this comes to expression in cultural phenomena such as fandom. To this extent, much of what I say in my chapter is true of other media texts in addition to Buffy, although Buffy and Whedon’s work in general have a special place in my heart.

TheoFantastique: Some readers might think it curious or inappropriate to think of something like Buffy the Vampire Slayer being considered in some way as religious. What hurdles do you face in making the case here?

TheoFantastique: Some readers might think it curious or inappropriate to think of something like Buffy the Vampire Slayer being considered in some way as religious. What hurdles do you face in making the case here?

Tony Mills: The biggest hurdle, as I allude to in the chapter, is overcoming a strict definition of religion which many people have. The interesting thing is that people from across the gamut of religious views are resistant to such a reading. There is an assumption among many, including most cognitive science of religion (or CSR) scholars, that “religion” is primarily about belief in supernatural agents. This is, in my opinion, something of a common sense view of religion and it is shared by conservative believers and ardent non-believers alike. Part of my motivation, although this chapter is not really the venue for it, is to get people to think about how their commitments in daily life often reflect the same psychological devotion and energy as the most steadfast churchgoers or even extremist terrorists. Although I consider myself to be an atheist, one of the things which bothers me about many atheists is the idea found among many of them that the only real problems in the world stem from the traditional religions and their violence. Certainly the violence done in the name of a god has been catastrophic, but it does not serve us to be blind to the violence and destruction wrought by the same mindless devotion to, say, a sports team, a nation, or a political ideology. Of course, to my knowledge Buffy and Star Trek fans and the like do not burn alleged witches at the stake, but even so we ought to be aware of how it is that we are wired for worship, community, sacrifice, ritual, and other aspects which are not strictly “religious” in the common sense of the term but are rather broadly human phenomena. So, by opening the definition of religion to get away from the idea that it’s only about god, my hope is to create awareness as well as to build bridges to those whom we judge as being crazy religious fanatics. There but for the grace of God go I, you could say.

TheoFantastique: Many people define religion in regards to belief, and belief in the supernatural and a personal God. Of course there are religions which don’t fit this mold, such as certain forms of Buddhism, so that type of definition is problematic. You are drawing upon the cognitive science of religion or the biocultural science of religion for your definition. Can you describe this a little, and how does this functional definition of religion dovetail with other approaches, such as the work of Clifford Geertz and a “thick description” of religion, and the idea of religion as a binding force from the Latin word religare?

Tony Mills: I’m definitely drawing on recent insights from scholars in the cognitive science of religion, but it’s interesting that, as I mentioned above, most of them still hold to the idea that religion is really about the origins and perpetuation of belief in supernatural agents. There is a minority strand of researchers, like Loyal Rue, who want to get away from that strict association because it is ultimately limiting and doesn’t help us to make sense of the broader human phenomena which come to expression in traditional religion, such as the impulses to ritual, devotion, worship, community formation, etc. You mentioned Buddhism. From my understanding original Buddhism is atheistic. Now, if you are committed to the idea that religion must include the worship of a supernatural agent, you will have a hard time understanding how Buddhism is actually a religion. From a broader approach, however, you can see Buddhism as a religion because it very much focuses on all those other human phenomena which are also part of traditional, supernaturalistic faith traditions.

Tony Mills: I’m definitely drawing on recent insights from scholars in the cognitive science of religion, but it’s interesting that, as I mentioned above, most of them still hold to the idea that religion is really about the origins and perpetuation of belief in supernatural agents. There is a minority strand of researchers, like Loyal Rue, who want to get away from that strict association because it is ultimately limiting and doesn’t help us to make sense of the broader human phenomena which come to expression in traditional religion, such as the impulses to ritual, devotion, worship, community formation, etc. You mentioned Buddhism. From my understanding original Buddhism is atheistic. Now, if you are committed to the idea that religion must include the worship of a supernatural agent, you will have a hard time understanding how Buddhism is actually a religion. From a broader approach, however, you can see Buddhism as a religion because it very much focuses on all those other human phenomena which are also part of traditional, supernaturalistic faith traditions.

Also, you mention that what I’m doing is a “functional” definition of religion, which is considered to be distinct from a “substantive” definition of religion, a distinction which I believe goes back to a particular twentieth-century religion scholar. I’m not sure who because classical religious studies was never my expertise. It’s a distinction, more simply, between what a religion does (its function) and what it is (its substance). I’ve always found such distinctions problematic because that kind of language goes back to Aristotle’s distinction between essence and accidents; but if, as David Hume asked, we can’t say anything about what a substance actually is, then are we actually talking about anything? I prefer a more organic or relational approach to such things, so for me, how religious devotion, worship, commitment, etc. function actually is its substance, to use that terminology.

As for Clifford Geertz, who represents traditional religious studies, I personally think that there is a lot to be shared between his approach of thick description and CSR approaches. It should be noted that not everyone in those two camps agree. Several CSR scholars ignore the insights of traditional religious studies because they feel that the older approach is limited, so they throw the baby out with the bathwater. Many in religious studies, as well as in the humanities more broadly, are leery of cognitive approaches to cultural phenomena such as religion because they sense biological determinism in the cognitive approach, not to mention the philosophical amateurism which pervades the usually simplistic theological assertions of many CSR writers.

As for Clifford Geertz, who represents traditional religious studies, I personally think that there is a lot to be shared between his approach of thick description and CSR approaches. It should be noted that not everyone in those two camps agree. Several CSR scholars ignore the insights of traditional religious studies because they feel that the older approach is limited, so they throw the baby out with the bathwater. Many in religious studies, as well as in the humanities more broadly, are leery of cognitive approaches to cultural phenomena such as religion because they sense biological determinism in the cognitive approach, not to mention the philosophical amateurism which pervades the usually simplistic theological assertions of many CSR writers.

But folks like Geertz are indispensible because they actually tell us what contemporary religion is like. CSR people often get so hung up on our evolutionary past that they forget that we really know more, and exponentially more, about how religion as it is lived today than how it was experienced in prehistoric times. Working with the details that Geertz and others offer allows us to analyze those details through the lenses of not only evolutionary psychology, but also of current cognitive neuroscience and many other fields. At the same time, I don’t think it has been observed often that Geertz, and Durkheim before him (whose magnum opus was written over a century ago), displayed intuitions of the importance of evolution and cognition for understanding religion and other cultural phenomena.

As for your final point on the etymological definition of religion as about binding, from the Latin religare, CSR has offered fresh insights on this. For major instance, it seems that early homo sapiens both formed more tightly knit communities and had more psychological incentive to see their communities succeed when they had a shared religion, specifically a shared view of supernatural agents, what these agents wanted, and how to make them happy and unhappy. CSR has only supported the view that religion is quite likely the most powerfully binding force in human history, which would also help explain the tenacity of fundamentalism in its various manifestations today.

TheoFantastique: You mention the emotional aspect of Buffyverse fan communities as the cohesive element. Can you talk to this a bit?

Tony Mills: This actually relates to my preceding comments about the binding force of religion, for therein it is not that there is a literal god or goddess who mystically binds people together for a common purpose, at least not from a scientific vantage. It is rather the psychological and emotional power which belief in said deities holds; e.g. that my tribe, my family, my nation, etc., is the best and most important and must be protected at all costs because my god demands it (and, you know, I will be punished if I don’t comply).

Tony Mills: This actually relates to my preceding comments about the binding force of religion, for therein it is not that there is a literal god or goddess who mystically binds people together for a common purpose, at least not from a scientific vantage. It is rather the psychological and emotional power which belief in said deities holds; e.g. that my tribe, my family, my nation, etc., is the best and most important and must be protected at all costs because my god demands it (and, you know, I will be punished if I don’t comply).

What I think happens often in fandom is that this same emotional significance and attachment is simply refashioned. Sure, Buffyverse fans have all sorts of different views on the divine and how one ought to live one’s life outside of conventions and other interactions (a shared if unconscious assumption which at least contributes to why, say, Angel-lovers and Spike-lovers don’t resolve their dispute through armed skirmishes), but the meaning and belonging they find in the shared communal love of Buffyverse media is, I argue, the same as that which has been provided by traditional religions. Perhaps the intensity is different. Perhaps there is not the same impulse to violent protection of values as there is in many religious contexts. But the emotions, the feelings of belonging, of being caught up into something bigger than oneself, are, I suspect, psychologically and neurologically the same.

TheoFantastique: You also describe group-specific vocabulary, esoteric knowledge, and ritual as important. Other scholars have noted similar things in regards to other forms of fandom, such as Star Trek and Star Wars. Have you given any consideration to attendance at fan conventions as a possible form of ritual paralleling pilgrimage in religious traditions?

Tony Mills: I’ve definitely considered attendance at fan conventions religiously significant, but I didn’t think of the parallel to religious pilgrimage per se independently, probably because in my own former faith tradition pilgrimage was not a priority. I’ve considered them more in terms of ritual and regular communal gathering. I have, however, come across one or two essays recently which address explicitly the parallel to pilgrimage. I would be happy to share them if I could recall where I found them! But my own knowledge of religious pilgrimage is too thin to comment further.

TheoFantastique: How do you see the breakdown of Berger’s “sacred canopy” of traditional religious plausibility structures, the democratization of knowledge and authority through the Internet, and the sacralization of popular culture playing a part in the religious function of Buffy fandom?

Tony Mills: Wow, this is a complex question, ostensibly composed of three parts. First, with regard to the sacred canopy and the related idea of the secularization thesis, I think that Buffy and pop culture fandom more broadly can be seen as evidence that Berger was wrong about the latter, a mistake he now readily admits. The evolved human needs for meaning, purpose, community, identity, nomos, and so on were never limited to the traditional religions—even if they found their most intense and systemic meeting therein—as Berger and others seem to have assumed, but have always been anthropological data, something which the cognitive and social sciences have helped us realize. This is precisely why even the monolith of industrial capitalism cannot permanently suppress those needs but must rather co-opt them in order to survive, which it is doing splendidly (hence the possibility and proliferation of fandom itself on a commercial level). The sacred canopy, in short, may look very different, but it is still there, one expression of which is demonstrated in Buffyverse fandom.

Tony Mills: Wow, this is a complex question, ostensibly composed of three parts. First, with regard to the sacred canopy and the related idea of the secularization thesis, I think that Buffy and pop culture fandom more broadly can be seen as evidence that Berger was wrong about the latter, a mistake he now readily admits. The evolved human needs for meaning, purpose, community, identity, nomos, and so on were never limited to the traditional religions—even if they found their most intense and systemic meeting therein—as Berger and others seem to have assumed, but have always been anthropological data, something which the cognitive and social sciences have helped us realize. This is precisely why even the monolith of industrial capitalism cannot permanently suppress those needs but must rather co-opt them in order to survive, which it is doing splendidly (hence the possibility and proliferation of fandom itself on a commercial level). The sacred canopy, in short, may look very different, but it is still there, one expression of which is demonstrated in Buffyverse fandom.

Second, with regard to the democratization of knowledge and authority through the Internet, I see this more as an expression of what was already in the air; an outcome of the late modern (or postmodern, if you prefer that term) breakdown of traditional authority structures, without which the Internet would either have not come into being at all, or would at least look very different than how we know it (perhaps still exclusive to military usage). Buffyverse fandom has flourished because of fans’ ability to communicate instantly with each other across the globe, a communication which, moreover, has included the sharing of fan-made videos, art, literature, and other media which are precisely not sanctioned by the established authorities, in this case the corporate conglomerates who own the legal rights to Whedon’s creations. In this sense there is something of a religious rebellion going on: people will find a way to worship despite the strictures of the clerical elite. This communication enabled by the Internet also means that, whatever fans decide about canonicity, they will continue to value texts created by each other and not only those by Whedon and those who own the rights.

Finally, the importance of the sacralization of pop culture for understanding Buffyverse fandom as religion should be evident, but I hesitate to make much use of this term because the sacred–secular dichotomy, like essence–accident, is another that I have tended to eschew in my analyses of cultural phenomena. Pop culture has always been sacred to the extent that it provides meaning, escape, hope, etc. to people. The breakdown of traditional religious observance has, I believe, intensified its importance (or sacredness, as it were) in contemporary Western life, but not in a way that would suggest that there has ever been a clear divide between “sacred” and “secular.” That being said, Buffyverse fandom would very likely not be possible in a world where the traditional religions had the influence they had, say, during the nineteenth century. Perhaps we can apply the term “sacralization,” then, to the phenomenon of the intensification of existential relevance of popular culture texts.

TheoFantastique: What other work have you done or do you have coming out in the near future?

TheoFantastique: What other work have you done or do you have coming out in the near future?

Tony Mills: My dissertation is being published by Routledge, I’ve been told in July, under the title American Theology, Superhero Comics, and Cinema: The Marvel of Stan Lee and the Revolution of a Genre. In the fall, Joss Whedon and Religion will be published by McFarland, a collection of essays which I co-edited along with you and J. Ryan Parker. It will be interesting to see the feedback we get from that within the Whedon fan community for sure.

TheoFantastique: Tony, thank you for research and willingness to discuss it here.

Tony Mills: My pleasure! Thanks for inviting me to do so.

The New Yorker: Into Darkness a ‘Drone Allegory?’